Harper Reed went from selling arty T-shirts to hunting for Obama voters.Photograph by Jacob Dehart

DURING THE 736 DAYS beginning May 9, 2010, Harper Reed walked an average of 8,513 steps, reaching a high mark of 26,141 on September 13, 2010, and a low of 110 on April 21 of this year. (His excuse: broken pedometer.) On that day, Reed, age 34.33 as of this writing, sent one tweet, 55 below his average. Reed was traveling from Chicago to Colorado, where he grew up, where he has spent 39.5 percent of his time away from home since 2002, and where, in 1990, he attended his first concert (David Bowie, McNichols Arena, row HH, seat 8). He has read 558 books in three years—roughly 1,350 pages per week at a cost of 4 cents per page. On May 11, 2011, he slept 14.8 hours before waking up at precisely 2:47 p.m. It was a personal best.

FLOWCHART: How Obama for America Gets to Know Jane Q. VoterOn his site, where he describes himself as “pretty awesome,” Reed painstakingly tabulates everything from his weight to his exact location. A certifiable hipster with gauged earlobes and an occasionally waxed handlebar mustache that complements his roosterlike crest of red hair, Reed is a veteran of the professional yo-yo circuit, a devotee of death metal, and a cofounder of Jugglers Against Homophobia. As chief technology officer for President Obama’s reelection effort—responsible for building the apps and databases that will power the campaign’s outreach—he and his team of geeks could provide the edge in a race that’s expected to be decided by the narrowest of margins.

FLOWCHART: How Obama for America Gets to Know Jane Q. VoterOn his site, where he describes himself as “pretty awesome,” Reed painstakingly tabulates everything from his weight to his exact location. A certifiable hipster with gauged earlobes and an occasionally waxed handlebar mustache that complements his roosterlike crest of red hair, Reed is a veteran of the professional yo-yo circuit, a devotee of death metal, and a cofounder of Jugglers Against Homophobia. As chief technology officer for President Obama’s reelection effort—responsible for building the apps and databases that will power the campaign’s outreach—he and his team of geeks could provide the edge in a race that’s expected to be decided by the narrowest of margins.

Over the last year and a half at the campaign’s Chicago headquarters, a team of almost 100 data scientists, developers, engineers, analysts, and old-school hackers have been transforming the way politicians acquire data—and what they do with it. They’re building a new kind of Chicago machine, one aimed at processing unprecedented amounts of information and leveraging it to generate money, volunteers, and, ultimately, votes.

Reed describes his campaign role as making sure technology is a “force multiplier.” And that’s about as much as he’ll say on the matter. The campaign declined to make Reed available for an interview, or to offer anyone who could so much as comment on the complexity of Reed’s mustache. “Unfortunately, we do not discuss anything that has to do with our digital strategy,” says spokeswoman Katie Hogan. Much of Reed’s work now is so under wraps that it’s literally code word classified—Obama for America (OFA) uses terms like “Narwhal” and “Dreamcatcher” to describe its high-tech ops. So in the spirit of the sweeping data-mining operation he helped build, I set out to learn as much as I could from Reed’s online footprint.

IN APRIL 2011, Reed arrived on the sixth floor of 130 East Randolph Street, the nerve center of the Obama campaign, by way of Chicago’s hacker circuit, where he was, by all accounts, a big fucking deal. After studying philosophy and computer science at Iowa’s Cornell College, he moved to the Windy City in 2001 and began spearheading dozens of digital projects of varying degrees of seriousness. WeOwntheSun.com, produced with two other future Obama hires, invited visitors to purchase plots of land on the surface of the sun (a steal at $4.95 per square kilometer). Eventually, he ended up at the online T-shirt retailer Threadless. It was there, in a converted Ravenswood Avenue print shop cluttered with go-karts, taxidermy, video games, and a full-size Airstream camper, that Reed, who rose to become the company’s chief technology officer, displayed the talents the campaign would later find so valuable.

Threadless wasn’t the first company to market arty apparel to the Wicker Park set, but its genius lay in its model. Its website functions as a sort of community center, inviting users to submit T-shirt concepts and vote on their favorites. Out of more than a thousand entries each week, a handful are selected. It’s almost impossible for a new T-shirt to flop because the target audience already has declared it a hit.

With Reed’s help, Threadless built a mini social network and seeded it with just enough incentives to boost its bottom line. Customers are advised on the precise number of shirts left in stock, prompting impulse buys. Profiles display a user’s level of involvement in real time. (Reed, for example, “has scored 281 submissions, giving an average score of 3.22, helping 10 designs get printed.”) The brilliance of Threadless is that it turned customers into workers, and the work itself into a game.

“Before Threadless, I loved users but didn’t trust them,” Reed told an interviewer in 2009, as he was leaving the company. But now he had no doubt: “Users are king.”

That faith in the power of crowdsourcing informed his other ventures. In 2008, Reed hacked the Chicago Transit Authority’s bus tracker app and made its information public. He also began looking for interesting ways to use it. Although he felt the system—for all its creaky “urine-soaked” cars—by and large worked, he wanted to understand what happened when it failed. Reed used the CTA’s data to track every incident, be it a downed power line or a deer on the tracks, and identify trends. Each day’s incidents were scored according to severity (low: 4; high: 90; average: 26). Freeing the data earned him an award from the city and face time with the agency. Another tool, a site called CityPayments.org that aggregated information on government contracts in Chicago, led to an official commendation from the White House.

Yet aside from volunteering briefly for the Obama campaign in 2008, Reed had shown little interest in political work. His plan post-Threadless was to take some time to experiment, immerse himself in cloud computing (he’s taken to calling himself a “nepholologist”—a mashup of the term for atmospheric analysts and LOL), and work with other startups. Then Michael Slaby, a veteran of the 2008 campaign who had been appointed chief integration and innovation officer, came calling.

When Reed joined OFA, he didn’t just bring his own expertise; he got the band back together. The campaign counts at least five Threadless alums among its Chicago tech staff, including Scott VanDenPlas, a self-described futurist who runs the campaign’s development operations (a hybrid of programming and IT), and Dylan Richard, the campaign’s director of engineering. A sixth Threadless colleague was invited to design the campaign’s online store, which borrows the layout and some of the crowdsourcing ethos from the company.

Reed’s mission is simple but ambitious: Assemble a data-mining infrastructure that allows the campaign to determine which voters to target and how to do it on a scale and scope that’s never been seen before. It’s part of a new, data-driven shift in the way campaigns are run. Think of it as the smart campaign.

THE USE OF DATA mining as a political tool traces its origins, at least in spirit, to 1897, when, in the aftermath of William Jennings Bryan’s first failed run for the White House, his wife, Mary, and brother, Charles, combed through letters from supporters for relevant personal information. They built a database of 200,000 index cards tracking things like a person’s religion, income, party affiliation, and occupation. It became the basis for the perennial candidate’s lucrative—although never victorious—direct-mail operation. Knowing your audience is at the heart of politics, but in the last decade, this precept has taken on a new dimension.

Obama’s first presidential campaign ushered in a new era of data collection and targeting. The operation’s new-media team, which included Facebook cofounder Chris Hughes (now owner and editor in chief of The New Republic), utilized social-media platforms to raise record sums from small donors and organize supporters. If an Iowa college student joined the Students for Barack Obama Facebook group, the campaign could follow up to ask him to knock on doors too. It also began to look for efficiencies in-house. Dan Siroker, who took a leave of absence from Google to work as director of analytics for the campaign, employed A/B testing to figure out which combination of images, text, and videos were most likely to compel BarackObama.com visitors to reach for their credit cards. (Siroker now provides those services to a vast array of commercial and political clients—including Mitt Romney’s campaign and Mother Jones—through his company, Optimizely.) All told, Siroker estimated A/B testing boosted OFA’s fundraising by $100 million, 20 percent of its online haul.

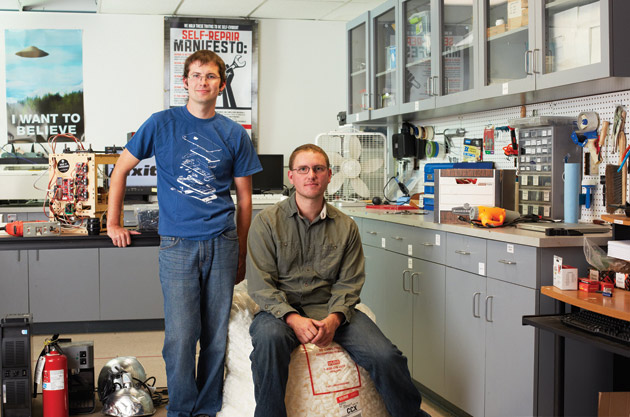

Meet other members of the tech team behind Obama for America.

Meet other members of the tech team behind Obama for America.

But the campaign struggled with integration gaps. When Reed volunteered his services the weekend before Super Tuesday in 2008, he spent most of his time manually entering voter data into spreadsheets. It was important work, but also tedious: Voter information collected online, via the campaign’s social-media platform, couldn’t be easily synced up with data gathered offline, by canvassers. The campaign could collect information by the terabyte—the Obama team, in fact, expanded the Democratic Party’s voter data by a factor of 10, accruing 223 million new pieces of info in the last two months of the campaign alone—but the issue was integrating and accessing it. That meant, for example, that a volunteer using the campaign’s much ballyhooed phone-bank app, which automatically provided volunteers with the names and numbers of voters, might waste precious time talking to a low-priority target. If in 2008 the Obama operation grew expert at unlocking new tools to mine data and target different constituencies, the challenge—and, by most indications, the major advancement—of 2012 has been to tear down the barriers preventing the campaign from taking full advantage of the information it amasses. That’s where Reed and his geek squad come in.

Campaigns typically draw on data from five sources. There’s your basic voter file, publicly available information provided by each state, which includes your name, address, and voting record. The party’s file, compiled by partisan organizations like VoteBuilder, includes more detailed information. Did you vote in a caucus? Did you show up at a straw poll? Did you volunteer for a candidate? Did you bring snacks to a grassroots meet-up? Did you talk to a canvasser about cap-and-trade? Contribution data, which the campaign compiles itself, includes both public information that campaigns disclose to the Federal Election Commission (FEC) and nonpublic data like the names of small-dollar donors.

By the 2000 election, political data firms like Aristotle had begun purchasing consumer data in bulk from companies like Acxiom. Now campaigns didn’t just know you were a pro-choice teacher who once gave $40 to save the endangered Rocky Mountain swamp gnat; they also could have a data firm sort you by what type of magazines you subscribed to and where you bought your T-shirts. The fifth source, the increasingly powerful email lists, track which blasts you respond to, the links you click on, and whether you unsubscribe.

In the past, this information has been compartmentalized within various segments of the campaign. It existed in separate databases, powered by different kinds of software that could not communicate with each other. The goal of Project Narwhal was to link all of this data together. Once Reed and his team had integrated the databases, analysts could identify trends and craft sharper messages calibrated to appeal to individual voters. For example, if the campaign knows that a particular voter in northeastern Ohio is a pro-life Catholic union member, it will leave him off email blasts relating to reproductive rights and personalize its pitch by highlighting Obama’s role in the auto bailout—or Romney’s outsourcing past. A ProPublica analysis revealed that a single OFA fundraising email came in no less than 11 different varieties.

Similarly, a canvasser in the field will use her smartphone or tablet to access certain personal info about the voters she’s trying to contact, and will also be able to call up tips on what issues to raise and what kind of pitch to make, which is derived from the campaign’s voter analytics. She is then able to enter more information—what worked and what didn’t, which issues resonated—directly into the system. The effect is to transform the historically tactile practice of canvassing into something more empirical.

But perhaps nothing has changed the game for political microtargeters more than the ubiquity of social networks. Privacy rules, which vary from site to site, technically render a lot of data inaccessible; Facebook’s terms of use limit the extent to which outside groups can mine the site. But the Obama campaign has found ways around those barriers too. One of the campaign’s most useful innovations in 2008 was to create a social-media platform, My.BarackObama.com, that encouraged its 2 million members to log in with their Facebook accounts. Those who did consented to the campaign’s harvesting some of their Facebook data.

Four years later, the campaign has grown even more sophisticated. Visit Dashboard, the 2012 organizing portal that Reed helped develop, and you’re given a never-ending variety of tasks designed to both engage you and learn more about you. If you sign your name to a petition on the site, that’s tracked. If, as you’re prompted to do time and again, you write a paragraph explaining what the campaign means to you, that text can be mined for relevant signifiers (say, support for LGBT equality) and added to your voter profile.

“I teach this, and to a T my students use the word ‘creepy,'” says Daniel Kreiss, a professor at the University of North Carolina-Chapel Hill whose new book, Taking Our Country Back, focuses on the rise of the Democrats’ digital machine. “In terms of just the sheer amount of data that political candidates have on you, I think everyone finds it creepy.”

In practice, the Obama team isn’t doing anything private companies haven’t already been doing for a few years. But the scope of its operation represents a major shift for politics—voters expect to be able to obsessively analyze information about the candidates, not the other way around.

For OFA, though, there’s no such thing as TMI.

REED REPRESENTS an approach to technology that distinguishes the Obama campaign from its counterpart in Boston. Whereas Romney has outsourced much of his data-focused operations, this time around Team Obama—which has been advised by representatives from Google and Facebook, according to Bloomberg Businessweek—is trying to emulate a start-up atmosphere in hopes of fostering the kind of innovation rarely associated with stuffy political shops. Fewer consultants, more in-house geeks.

“[They’ve] taken this sort of data-driven mentality and expanded it across the entire campaign,” says Josh Hendler, the former director of technology at the Democratic National Committee, who’s staying on the sidelines in 2012. Dashboard, for instance, mimics some of the gaming tactics that Threadless pioneered. Volunteers can see their personal statistics updated in real time—money raised, calls attempted, conversations held, one-on-one meetings convened. A scoreboard allows volunteers to see how they stack up against their peers. The campaign, in turn, can use this data to gauge which field offices are hitting their goals and which ones aren’t.

As the campaign becomes ever more absorbed in all things digital, its real-world networks have shifted accordingly. One of Reed’s first moves as CTO was to fly with Slaby to San Francisco, where they held an information session for techies at Zeitgeist, a popular Mission District beer garden. In February, OFA unveiled a new satellite technology office in the city’s ultra-wired SoMa neighborhood, the first of a handful of such offices slated to open across the country.

Romney’s Boston campaign operation, by contrast, had no software engineers on staff until well after the end of the primary season, according to a Mother Jones analysis of payroll data provided to the FEC. Its forays into the digital world have caught attention mostly for their miscues, like an iPhone app that featured a misspelled “America.” But the campaign has quietly begun tackling the same challenges faced by OFA, only with a twist. Slate‘s Sasha Issenberg reported in July that the campaign had recently hired eggheads from places like Google Analytics and Apple in an attempt to reverse engineer the Obama campaign’s strategy. Hence Team Obama’s shroud of secrecy around its digital ops.

It’s ironic that Romney’s 2012 campaign is reduced to such a reactive mode since the former consultant was himself an early convert to the data-centric campaign. When Alex Lundry’s conservative analytics shop, TargetPoint, approached the Massachusetts gubernatorial candidate in 2002 with the idea of using analytics to identify voters, Romney’s Bain confidants were stunned: “You mean they don’t do this in politics?”

Lundry signed on this summer to lead Team Romney’s data efforts but, overall, the campaign has favored contracting the work of microtargeting to private firms. The good news for Romney is that it’s never been easier to buy off the rack. As of late June, the Romney campaign had paid $13 million to Targeted Victory, whose cofounder, Zac Moffatt, is also the campaign’s digital director. Moffatt brags that his firm can beam totally different messages to two voters in the same house. That’s 2005 stuff for commercial advertisers, but in the political world it still counts as innovation.

At Moffatt’s direction, Romney is placing an emphasis on “off the grid” voters—the roughly 30 percent of voters who Moffatt has determined don’t watch enough live television to be swayed by commercials. It’s a number that will only increase as more and more people consume media on handheld devices or DVR their favorite shows.

In 2010, Targeted Victory began employing Lotame, a company that uses cookies to track your online habits—everything from the websites you comment on to the articles you share with friends. To gauge voter sentiment it even crawled Huffington Post comment sections, according to the Wall Street Journal. (Huffington Post says it ended its relationship with Lotame after the incident due to privacy concerns.) Asked about the company’s political operations, a spokesman says, “Lotame has been asked to stop talking about it.”*

The line between data mining and cyberstalking is already blurred, especially in the commercial sector. To illustrate their powers, analysts like to point to Target, which used a 25-element “pregnancy prediction score” that guessed online shopper’s due dates. Political campaigns are just catching up, but once they do, their privacy practices may be tougher to control because of the protections afforded to political speech. “Basically we have a new world of information management that has emerged, and it’s a world that may well claim total impunity from regulation,” says Joe Turow, a University of Pennsylvania professor studying voter attitudes toward political data mining.

Crunching data can only take a campaign so far. Microtargeting can help candidates squeeze more dollars out of their supporters, and more value out of those dollars; it can’t change the prevailing political environment. Yet in a tight race—and today, presidential elections come down to a handful of percentage points—obsessive intelligence-gathering can provide a critical edge. “If it’s close, you’re absolutely talking about winning and losing the election based on the quality of your data, and the quality of the program,” Hendler says.

IN LATE JUNE, as I finished hoovering up the online traces of the man tasked with assembling the president’s data-mining operation, Reed was polishing off book number 558, A.I. Apocalypse. It’s about a high school computer geek who accidentally unleashes an out-of-control AI program that threatens to overwhelm the world.

Among technologists, singularity—the idea that technological forces will one day usher in a new form of superintelligence that will forever change civilization—is something of a Holy Grail. It’s a vision of the future with plenty of appeal for someone who, like Reed, owes his career to the power of collective intelligence. His bio on his personal website notes, right after name-checking Threadless, “I am patiently waiting for the singularity.”

The rise of the genius machines probably won’t come in 2012. Until then, Harper Reed will have to do.

*This paragraph has been revised from its original print version.