Elena Yakusheva/Shutterstock

The Supreme Court will hear arguments on Tuesday in McCutcheon v. Federal Election Commission, a case that’s been dubbed “the next Citizens United.” The plaintiff, GOP donor Shaun McCutcheon, and his conservative allies say the case is about getting rid of restrictions on political spending that stifle free speech. Campaign finance watchdogs, meanwhile, fear the case could eviscerate an important piece of what’s left of the federal laws governing money in politics. McCutcheon, says Fred Wertheimer, president of Democracy 21, will decide “whether we return to the system of legalized corruption we have had in the past and that has led to some of the worst Washington corruption scandals in the nation’s history.”

Here’s what you need to know about the case.

What’s this case about? During the 2012 election season, McCutcheon, an electrical engineer who lives in Alabama, started making donations to all the candidates he supported. He made (PDF) many $1,776 donations, a few for a couple thousand dollars, always staying within the donation limit of $2,500. Eventually, though, McCutcheon bumped into a different limit: the cap on the overall amount of money a single donor can dole out. Political donors can give no more than $123,200 during the two-year election cycle—$48,600 to federal candidates and $74,600 to political parties and related committees. McCutcheon believed the aggregate limit was unreasonable and unconstitutional, and so, with the backing of the Republican National Committee, a coplaintiff in his case, he sued his way to the Supreme Court of the United States.

At stake in McCutcheon is whether it’s constitutional for the government to cap overall donations made by a single political donor. McCutcheon, his lawyers, and their conservative allies say the limit curbs First Amendment rights and does little to guard against corruption or the appearance of corruption, the court’s justification for placing limits on political giving and spending. On the other side, campaign finance watchdogs and their lawyers say ending the aggregate limit would create a system in which wealthy donors could cut multimillion-dollar checks to candidates and parties, making Republicans and Democrats alike even more beholden to wealthy contributors.

What’s the precedent? The Supreme Court’s landmark 1976 case Buckley v. Valeo upheld the overall contribution limit, at the time set at $25,000 for every two-year cycle. “The court held that limiting the amount of contributions imposed only a ‘marginal’ restriction on speech (since the important thing was the act of contributing, not the amount),” explains University of California-Irvine law professor Rick Hasen. “And the court said the government’s interest in preventing corruption and the appearance of corruption justified that marginal restriction.”

But the current Supreme Court, led by Chief Justice John Roberts, has not been shy about overturning precedent when it comes to campaign finance. Citizens United, the court’s 5-4 majority opinion (“orchestrated” by Roberts, according to The New Yorker‘s Jeffrey Toobin), surprised many legal observers by overturning two previous decisions, 1990’s Austin v. Michigan Chamber of Commerce and 2003’s McConnell v. Federal Election Commission. The Roberts court has previously argued that some donation limits are constitutional (see: 2006’s Randall v. Sorrell), but it is quite possible that the court will take a big bite out of Buckley by knocking down the overall donation cap.

What happens if the overall donation cap is eliminated? Campaign finance watchdogs and supporters of tough campaign regulations say if McCutcheon prevails a single donor will be able to give nearly $3.7 million (PDF) by maxing out his or her donations to every candidate of his preferred political party, every state committee of that party, and the national party and its affiliated committees. With the overall limit scrapped, watchdogs argue, party operatives could create mega-fundraising committees that can solicit seven-figure checks and then spread the money far and wide within their party at the federal and state level.

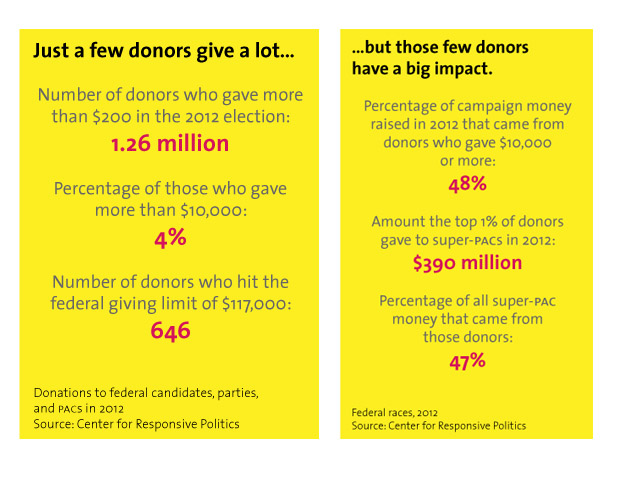

Big donors would be free to dole out far more money if the cap went away. The left-leaning think tank Demos found that 1,219 top-tier donors donated $155.2 million to candidates, parties, and PACs in the 2012 cycle. Without an aggregate contribution limit, Demos projects that those same donors would have given $459.3 million. And who are these elite donors? According to a Sunlight Foundation analysis, two-thirds of the top 1,000 donors in 2012 primarily gave to Republicans, and more than a third hailed from the financial sector.

Here are two charts showing how just a sliver of political donors do most of the giving:

McCutcheon, the RNC, and their supporters, who favor few if any money-in-politics regulations, say the worst case scenario advanced by watchdog groups is speculative scaremongering. “There is no evidence, before or since imposition of the aggregate limit, that donors have used such schemes to circumvent the $2,600 candidate limit,” Brad Smith, a former Federal Election Commission member, wrote in the Wall Street Journal.

But wait—isn’t Sen. Mitch McConnell somehow involved? Yes. As part of McCutcheon, the Supreme Court has agreed to let a lawyer for the Kentucky Republican argue before the court on Tuesday. The Senate minority leader is a vehement foe of campaign finance regulations: He led the fight to overturn the 2002 McCain-Feingold law with his suit, McConnell v. FEC, which he lost, and he has repeatedly filibustered Senate bills to beef up disclosure of dark money spending in our elections.

This time, McConnell wants to go even farther than McCutcheon: He plans to argue, through his lawyer, that the court should revisit the underlying legal principle that justifies whether there should be any limits on contributions to candidates. The Campaign Legal Center calls McConnell’s argument “the grenade in the McCutcheon briefs.”

Is this really Citizens United 2.0? It could be. If McConnell gets his way, and the Supreme Court opens the door to eliminating individual donation limits, the McCutcheon case will have struck a blow at the heart of the campaign finance laws enacted after Watergate. “The McCutcheon case—and Senator McConnell’s amicus brief—thus may appear to target a single discrete law,” writes the Campaign Legal Center’s Trevor Potter, “but actually threatens to overturn a core principle of American campaign finance law.”