The Nebraska Supreme Court ruled on Friday that a 16-year-old could not get the abortion she wanted because she “was not mature enough to make the decision herself.” The Court’s ability to force the teen, a ward of the state known only as Anonymous 5, to carry her unwanted child to term is a direct result of the state’s 2011 parental consent law that requires minors seeking an abortion to get parental approval.

But Nebraska is not unique: similar rulings could happen in most other states across the country. Laws that mandate parental involvement in teens’ abortions offer anti-choice judges new opportunities to limit abortion access. And while it is unclear whether such parental involvement legislation affects minors’ abortion rates in general, Sharon Camp, former president and CEO of Guttmacher Institute, wrote in an article for RH Reality Check that such mandates can put teens at risk of physical violence or abuse and “result in teens’ delaying abortions until later in pregnancy, when they carry a greater risk of complications and are also more expensive to obtain.” The case of the Nebraska teen also shows that parental involvement legislation overlooks wards of the state, leaving pregnant young adults who have no legal parents at the behest of the court system.

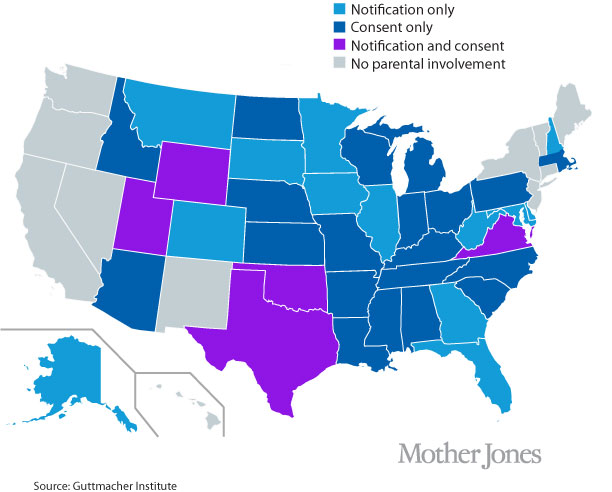

Here’s a map of parental consent laws across the United States:

According to Guttmacher, “only two states and the District of Columbia explicitly allow” all minors to consent to their own abortions. On the other hand, a whopping 39 states require some kind of parental involvement in a minor’s decision to have an abortion.

There are two major types of legislation mandating parental involvement in their child’s decision to have an abortion: Parental consent and parental notification laws. Parental consent laws mandate that a minor who has decided to get an abortion first get the OK from either one or both of her parents (or her legal guardian). Parental notification laws, on the other hand, require that a parent or legal guardian be notified of a child’s decision to get an abortion, either by the minor herself or by her doctor. Eight states, including Nebraska, mandate a notarized statement of consent from a parent before the abortion is performed. And in Arkansas, the Governor recently signed a law making it a crime to assist a minor in obtaining an abortion without her parent’s consent, “even if the abortion was performed in a state where parental consent is not required.”

Almost all states with parental involvement laws include some exceptions to the rules. Many states allow exceptions in medical emergencies or in cases of abuse, assault, incest, or neglect. Only a handful of states extend their consent or notification laws to other adult relatives, like grandparents.

But one exception in particular has increased the role of the courts in the personal decision-making of teens. As a result of a Supreme Court ruling that parents cannot have complete veto power in determining whether their child gets an abortion, almost all states offer a “judicial bypass” to their parental involvement laws. The bypass allows minors to go to the courts to waive their state’s involvement laws; but in effect moves the power to veto a teen’s abortion from her family to the courts.

And here is where the Nebraska case comes in. In this case, the biological parents of Anonymous 5 had previously been stripped of their legal parental rights after physically abusing their daughter and, as a result, the pregnant teen had no legal parents and was instead a ward of the state. With no parent to consent to her abortion, she was forced to ask permission from the courts, who then denied her request, essentially finding her mature enough to carry a baby she doesn’t want but too immature to consent to her own abortion. Instead of offering an alternative to parental consent, the courts serve as just another barrier between teens—especially wards of the state—and access to safe abortion services.