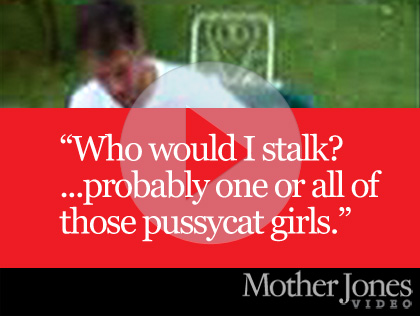

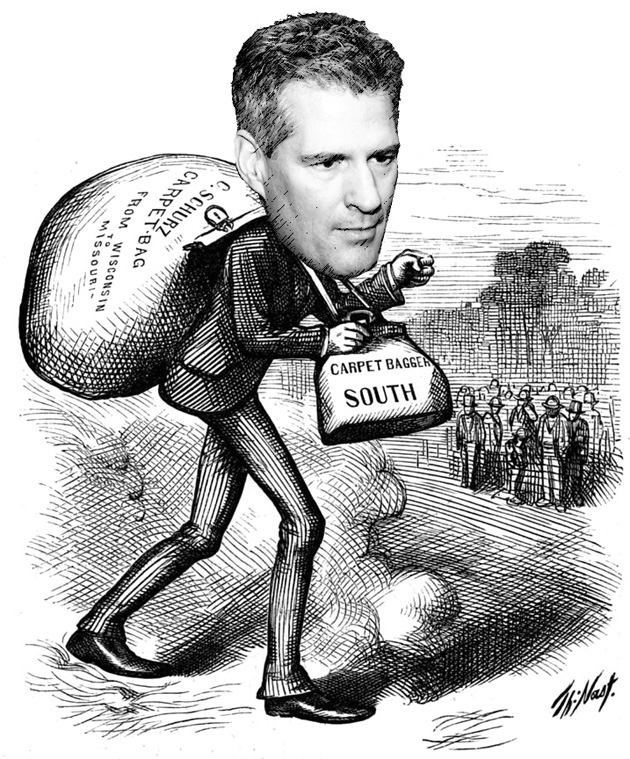

Scott Brown has a carpetbagging problem. On Monday, the former Republican senator from Massachusetts—who is now running for Senate in New Hampshire—defended his Granite State bona fides by taking a page from Lisa Simpson: “Do I have the best credentials? Probably not. ‘Cause, you know, whatever.”

At this point, it’s the rare Brown story that doesn’t at least allude to the dreaded C-word. “Carpetbagger or Comeback Kid?” asked the Washington Examiner‘s Rebecca Berg. “Scott Brown’s first hurdle in the Granite State will be addressing the carpetbagging charge,” argued US News & World Report‘s David Catanese. Respondents to a March poll from Suffolk University, a plurality of whom disapproved of Brown, used words like “carpetbagger” and “interloper” to describe the ex-senator. His opponent in the Republican primary, former Sen. Bob Smith, has even offered to buy Brown a road map to the state—although Smith has run for Senate in Florida twice in the last decade.

If Brown wants to go back to Washington next winter, he should probably come up with a better response than “whatever.” But his critics in Washington have it all wrong. For more than a century, carpetbaggers have gotten a bad rap for all the wrong reasons.

The term “carpetbaggers” traces its origins as a political cuss word to the 1860s, when thousands of Northerners moved to the occupied South during Reconstruction in pursuit of political and economic opportunities. (A carpet bag was a kind of luggage.) The war had left a vacuum: Hundreds of thousands of White Southern males had been killed; many of the survivors were former Confederate politicians, who were forbidden to seek political office. Along with “scalawags”—Southern whites who supported Republicans—the carpetbaggers were the villains of Reconstruction. But like a lot of what happened during Reconstruction, that historical narrative, reinforced by a century and a half of Southern historians, is not quite right.

“Some Northerners who went to the South were corrupt, most were not, and many were more willing to defend the basic rights of the former slaves than most white Southerners—which is why they were vilified,” says Eric Foner, a history professor at Columbia who specializes in the Reconstruction South. The label applied only to certain kinds of outsiders. As Foner puts it, “If you came South and joined up with the Democrats, you were a gentleman, not a carpetbagger.”

So it’s not that the carpetbaggers were simply relocating. The problem was that they were interfering with Democrats’ attempt to act as if the Civil War had never happened. A good example of this is Albion Tourgée, a Civil War vet from Ohio who moved with his wife to North Carolina in 1866 and was immediately slapped with the C-word when he was appointed superior court judge. Among his sins: pushing for equal protection, free public education, and eliminating property requirements to vote. (Later in life, after retreating to New York state, Tourgée was the losing lawyer in Plessy v. Ferguson, the Supreme Court that enshrined the doctrine of “separate but equal” treatment for blacks and whites.)

The reaction to carpetbaggers was venomous. In 1868, the Independent Monitor in Tuscaloosa, Alabama, ran a cartoon depicting two white men with luggage marked “Ohio” being lynched by the Klu Klux Klan, represented by a donkey. Maybe we shouldn’t take seriously the character judgment of a people who believed carpetbagging was a sin but domestic terrorism wasn’t.

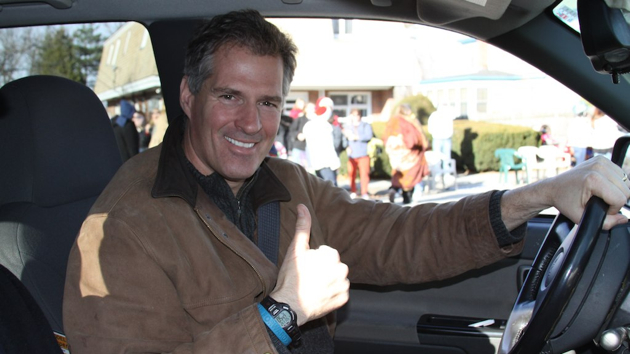

If we are stuck with “carpetbagger” as a catch-all for political migrants, that doesn’t mean carpetbagging is a bad thing. Politicians try their luck in different states because people know what they’re getting. Robert Kennedy wasn’t a native New Yorker when he decided to run for Senate there in 1964 (his roots were in Massachusetts), but he had been attorney general of the United States. That’s a good person to have working for you if you want to exert political influence, and baseball rivalries aside, there aren’t a lot of substantive differences between New York Democrats and their Massachusetts counterparts. Ditto for Hillary Clinton, who bought a house in New York to run for Senate after three decades in Arkansas and Washington, DC. Brown, who does own a home in New Hampshire, was recruited to run there because he is the rare Republican who has been elected to a statewide office in New England recently.

Besides, moving to a new state for work is the American way. New Hampshire’s economic pitch is based on luring Massachusetts residents with the promise of a low tax burden, and (for some reason) the freedom to ride motorcycles without helmets. Some activists in the state are more explicit about their desire to attract carpetbaggers. The Free State Project aims to turn New Hampshire into a libertarian paradise through a mass migration of Ayn Rand acolytes—nearly a dozen of whom have already been elected to the state’s 424-member Legislature.

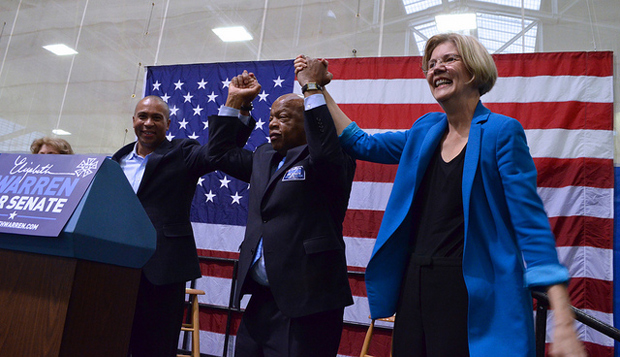

The good news for Brown, whose 2012 reelection campaign leveled the carpetbagger charge against the Oklahoma-raised Elizabeth Warren, is that his electoral fate will probably be decided by something other than his residency—such as the sizable policy differences between him and incumbent Democratic Sen. Jeanne Shaheen. So Brown should probably decide how he feels about expanding Medicaid coverage—a core part of the Affordable Care Act that’s supported by two-thirds of New Hampshire voters—sooner rather than later.

Or, you know, whatever.