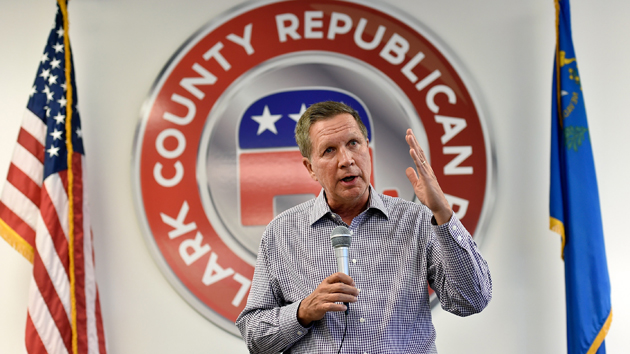

John Kasich: Charlie Neibergall/AP; Anti-Abortion Sign: <a href="http://www.shutterstock.com/cat.mhtml?lang=en&language=en&ref_site=photo&search_source=search_form&version=llv1&anyorall=all&safesearch=1&use_local_boost=1&autocomplete_id=&searchterm=pro%20life&show_color_wheel=1&orient=&commercial_ok=&media_type=images&search_cat=&searchtermx=&photographer_name=&people_gender=&people_age=&people_ethnicity=&people_number=&color=&page=1&inline=23727508">Melissa Brandes</a>/Shutterstock

Ohio, a state often considered ground zero for anti-abortion legislation, finds itself at the center of the latest reproductive rights controversy—one that could force its governor, Republican presidential candidate John Kasich, to take an uncomfortably public stance.

A bill approved in June by a health committee in the Ohio House of Representatives, on a bipartisan 9-3 vote, would ban physicians from performing abortions on women who want to terminate their pregnancy because of a prenatal diagnosis of Down syndrome. The legislation shifts the reproductive rights conversation from its typical preoccupation with time frame and viability to the more nebulous question of a woman’s motivation for ending a pregnancy.

“This is a new type of attack on access to abortion care,” says Kellie Copeland, executive director of NARAL Pro-Choice Ohio, an abortion rights advocacy group. “It’s restricting access to abortion based on the reason that a woman makes a decision.”

The bill, which was written with the help of Ohio Right to Life, is expected to pass the Ohio state legislature—more than two-thirds of whose members have been endorsed by the National Right to Life Committee—before heading to Kasich for a signature.

Since entering office in 2011 Kasich has signed every anti-abortion measure that has landed on his desk, enacting a total of 16 restrictions that limit abortion access and family planning opportunities, and resulting in the closure of half the state’s abortion clinics. There is little reason to think this bill will be different.

“I am very confident that he will sign the bill,” says Michael Gonidakis, president of Ohio Right to Life. Gonidakis adds, “There is no candidate running for president who has done more for the pro-life movement than John Kasich.”

While Kasich is quick to share his pro-life beliefs, his actual abortion record has not been so widely broadcast, because the restrictions he has enacted have been slipped into big, complex budget bills. This legislation, however, forces Kasich, who has largely been labeled a moderate in a GOP race filled with candidates further to the right, to take a broadly publicized stance on a relatively new type of abortion legislation. Only North Dakota has enacted similar legislation, when in 2013 it banned abortions based off diagnoses of Down syndrome, the sex of the baby, or the potential for a genetic abnormality.

Kasich has not yet commented on the bill. “The governor is pro-life and believes strongly in the sanctity of human life, but we don’t take a public position on every bill introduced into the Ohio General Assembly,” his spokesman Rob Nichols tells Mother Jones in an email.

For decades, Ohio has been considered a testing ground for new abortion measures. It was the first state to consider the controversial heartbeat bill, which would have banned abortions at six weeks, when the fetal heartbeat can be heard. The bill did not pass, but it sparked copycat legislation. “It’s very strategic. If you can get something established in Ohio, all the other Midwestern states are going to start doing the same thing,” explains Gonidakis, who was appointed by Kasich to the state medical board in 2012. Gonidakis believes Ohio’s diversity of people and mix of urban and rural environments make the state a great choice for anti-abortion legislators who want to experiment with new bills. “We do not have a monopoly on good ideas, but we’re a good testing ground,” he says.

Abortion rights advocates like Copeland find themselves in a more difficult position. With little precedent for legislation like this, they lack a barometer to assess its likely impact.

Under the bill, a doctor found guilty of knowingly performing an abortion on a woman who made her decision because of a Down syndrome diagnosis could face up to 18 months in prison. That could prove nearly impossible to enforce, given the multitude of factors that go into an abortion decision. But abortion rights advocates still fear the repercussions the bill could have for the medical profession and abortions at large.

“It’s clearly bad medicine. It’s designed to have a chilling effect on physicians,” says Copeland, who views the legislation as a way to discourage doctors from providing abortion care for patients. She worries the bill will also affect the amount of information women share with their doctors. “This is not the doctor-patient relationship that we should have in this state.”

Supporters of the bill, like Gonidakis, insist it’s about discrimination as much as abortion. “We spend so much money helping people with developmental disabilities, or physical disabilities and special needs,” he says. “Why don’t the same rules apply while they are developing in the womb?”

Critics contend that those pushing for the measure have done little to help people with Down syndrome. A 2013 report from Policy Matters found that there were 30,000 people with disabilities in Ohio on a waiting list for services. “Down syndrome is being exploited for the political purpose of continuing to eliminate abortion care,” says Copeland.

According to a 2012 report from researchers at the University of South Carolina, between 60 percent and 90 percent of women nationally who receive a prenatal diagnosis of Down syndrome have an abortion. David Perry, an Illinois-based journalist and father of an eight-year old son with Down syndrome, has been a public opponent of the bill, arguing that it’s the wrong approach to ensuring equity and dignity for individuals with the condition.

“If you really want to reduce the rate of abortions based on prenatal diagnosis, then what you do is make Down syndrome less scary,” says Perry. “You don’t say, ‘You’re going to go to jail if you do this.'”

Abortion rights lawyers view the legislation as an encroachment on Roe v. Wade, which allows women to have an abortion until the point of viability. They see the bill as part of an incrementalist approach that chips away slowly at abortion rights, a strategy Gonidakis endorses and praises Kasich for adopting.

“There are some candidates out there who give a great speech on the pro-life issue, but there are very few candidates like John Kasich who can say, ‘Here’s my body of work,'” says Gonidakis, who expects the bill to land on Kasich’s desk by the Thanksgiving break. “Actions do speak louder than words. The proof is in the pudding, and you can just look at the results here in Ohio.”