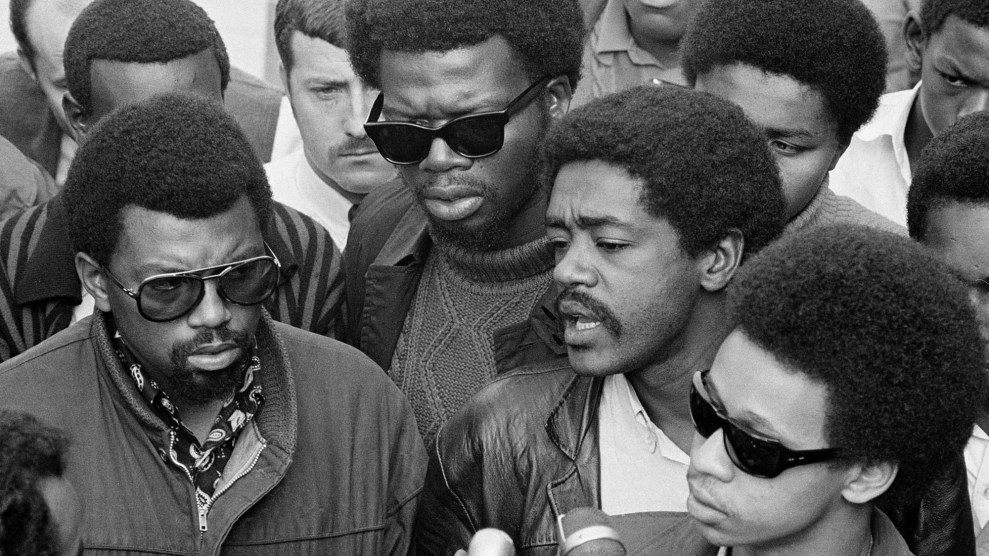

Ben Stewart, left, head of the Black Students Union at San Francisco State University; George Murray, center with dark glasses, a teacher who was suspended from the university; and Bobby Seale, right, chairman of the Black Panther Party, at a press conference in Oakland, California, on November 21, 1968. AP Photo/Ernest K. Bennett

“Don’t talk race, assimilate. Find a way to purge who you are.” That’s what Ramona Tascoe’s father told her when she was young. Tascoe, a former member of the nation’s first Black Student Union, was born in Louisiana, but her family moved to San Francisco in 1953. When they got to California, her parents were determined to help their children succeed. That meant, they believed, eradicating any signs of black culture. The young Tascoe pressed her hair straight and practiced pulling in her lips to make them seem thinner.

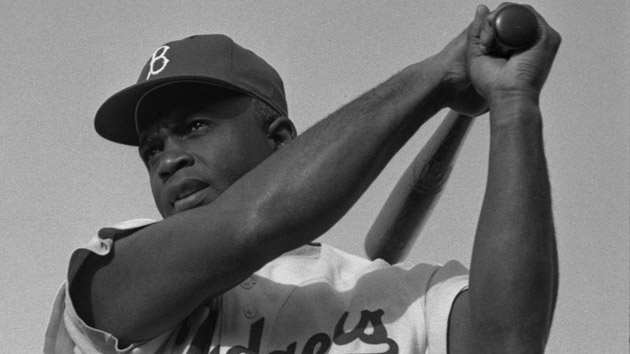

When she was ready to go to college in the mid ’60s, Tascoe enrolled at San Francisco State University. At the same time, California was in the middle of a growing black cultural and political revolution—the Black Panthers were headquartered across the Bay in Oakland, and the NAACP was protesting de facto segregation of public schools in San Francisco. The black-power organizers were rejecting the emulation of white beauty standards and cultural norms, and calling for schools and universities to embrace black history and the arts. Tascoe joined the school’s Black Student Union, and by 1967, she became the first San Francisco State student arrested during what is still the longest college strike in US history, and what would turn out to be a seminal event that shaped higher education.

Here’s what happened: In 1968, SF State faculty member George Murray joined the Black Panther Party and encouraged students to carry arms. In response, the administration asked the schools’ president, John Summerskill, to fire Murray. Summerskill refused and was replaced by a president who did fire Murray. This sent the Black Student Union into protests and demonstrations. In response, the new president brought in the cops. To this day, those demonstrations are remembered as some of the bloodiest in university organizing; more than 500 students were arrested and hundreds of students were left with severe injuries. The violence radicalized and politicized many other people on campus in support of the protesters. After five months and hundreds of arrests, the strike ended—but not before the university agreed to establish the new College of Ethnic Studies. Within a year, every state campus in California had a Black Student Union that was pushing for similar reforms. Inspired by the organizers, Latino and Asian American students formed their own unions on college campuses. And similar protests took place at the University of Wisconsin, City College of New York, Duke, and Brandeis University. “It’s the higher education counterpart to Board v. Brown of Education,” said Juanita Tamayo-Lott, the former San Francisco State student leader.

A new documentary, Agents of Change, describes the five-month SF State protest and a similar strike at Cornell University through the voices of former students like Tascoe who were involved. The film is a gripping case study of the meticulous organizing, community engagement, and careful planning that went into two of the most effective student strikes in American history.

The film was recently screened at San Francisco State in front of an audience of students who were involved in their own strike. For several months, students at the university have been protesting proposed budget cuts to the very same Ethnic Studies College that was born out of the 1968 strike. On May 2 this year, four of the student activists began a hunger strike. (The students dubbed their group the Third World Liberation Front 2016—an homage to the 1968 organizers depicted in the film.)

Agents of Change, produced by Frank Dawson and Abby Ginzberg, is the first feature-length documentary about the founding of the SF State College of Ethnic Studies. The film is full of fascinating, archival footage, but its most important point is the central role that black students played in the fight to reform American universities: most notably, they pushed for the expansion of Eurocentric curricula to include intellectual contributions of other racial and ethnic groups, for the hiring of more diverse faculty and better recruitment, and for more humane treatment of students of color.

In the ’60s at SF State, Black Student Union members worked hard to recruit students of color like Tascoe who were from working-class families to attend the predominantly white university. By 1967, the black population at SF State had doubled, and a year after that, it doubled again, according to the San Francisco Chronicle. The group also recruited faculty members, including prominent black intellectuals such as the writer Amiri Baraka and the poet Sonia Sanchez. In the film, Sanchez, who taught at SF State from 1968 to 1969, recalls, “The black students didn’t know anything about themselves. I was in the classroom, writing names [on the blackboard]: Langston Hughes, Du Bois, Richard Right, Marcus Garvey. And I said, ‘Which of the names [do] you recognize?’ ‘MLK and Malcolm.’ That was it. Can you imagine?” Around the same time, student union members drafted a document called, “The Justification for Black Studies.”

Nearly 50 years later, all but one of the 23 campuses that are part of the California State University system offer ethnic studies classes. According to Dylan Rodriguez, the chair of the ethnic studies department at the University of California-Riverside, “the departments that sprang up all over the country are the product of ordinary social and student movement organizing. That sets them apart from all other institutions in higher education.”

Between 1975 and 2000, the number of ethnic studies programs more than doubled in American universities, according to the most recent 2009 John Hopkins University study. That was a good thing, argues Christine Sleeter, a professor of education at California State University-Monterey Bay who is known for her research on curriculum. In 2011, Sleeter reviewed dozens of studies and research reviews on the impact of ethnic studies classes in universities and public schools, and found that in all but one study the students’ academic achievement improved. A 2016 Stanford study of three high schools in San Francisco that implemented an ethnic studies pilot program also found that students in the course improved their overall grades, their attendance rates, and the number of course credits they earned. In the last five years, at least nine school districts in California and others in Arizona and Texas are looking at the possibility of expanding their high school curricula to include more ethic studies courses, according to Sleeter.

But just as ethnic studies course offerings are expanding at the high school level, they have been in trouble at the college level over the last seven years, as states have searched for ways to reduce budget holes caused by the recession. At the same time, student interest and enrollment in ethnic studies is growing on many campuses, which is why so many students have protested these cuts. In 2011, students at the University of California-Berkeley staged a hunger strike to stem the budget cuts in their ethnic studies program. Two years later, 250 students at Temple University in Philadelphia marched to protest proposed cuts to faculty positions in the department for African American studies. Yearly cuts to ethnic studies programs in California prompted Timothy White, chancellor of the California State system, to establish a temporary moratorium on significant changes to ethnic studies programs in 2014—and to create a task force to survey the state of ethnic studies programs and suggest steps to strengthen them. The final report is still being refined, but a 2015 draft copy surveying 23 campuses found that all ethnic studies departments reported dramatic cuts. More than half of them have gotten smaller since the recession, with increased class sizes, and have reported that they are unable to replace faculty members whenever someone leaves or retires.

Danny Glover: “They’re trying to gentrify this education. But [the college of ethnic studies] is what this city is.” pic.twitter.com/ws3o8NHbgP

— Jamilah King (@jamilahking) May 9, 2016

Agents of Change documents some of what is happening today, but importantly it highlights the growing resistance to these cuts, often in alliance with the Black Lives Matter activists on college campuses. On May 11, San Francisco State President Leslie E. Wong and four hunger strikers signed an agreement that—bucking the national trend—increased funding for the Ethnic Studies College by 14 percent. “I’m hoping that our film will reach college campuses especially and illustrate just how much student activism matters,” Ginzberg said a few days after the signing of the agreement. “The screening at San Francisco State University was so inspiring. The students there are so savvy. They know the history, they are engaged with the local communities, they are strategic, and they know this is a fight that needs to be refought over and over again.”