Chapter 1: “Inmates Run This Bitch”

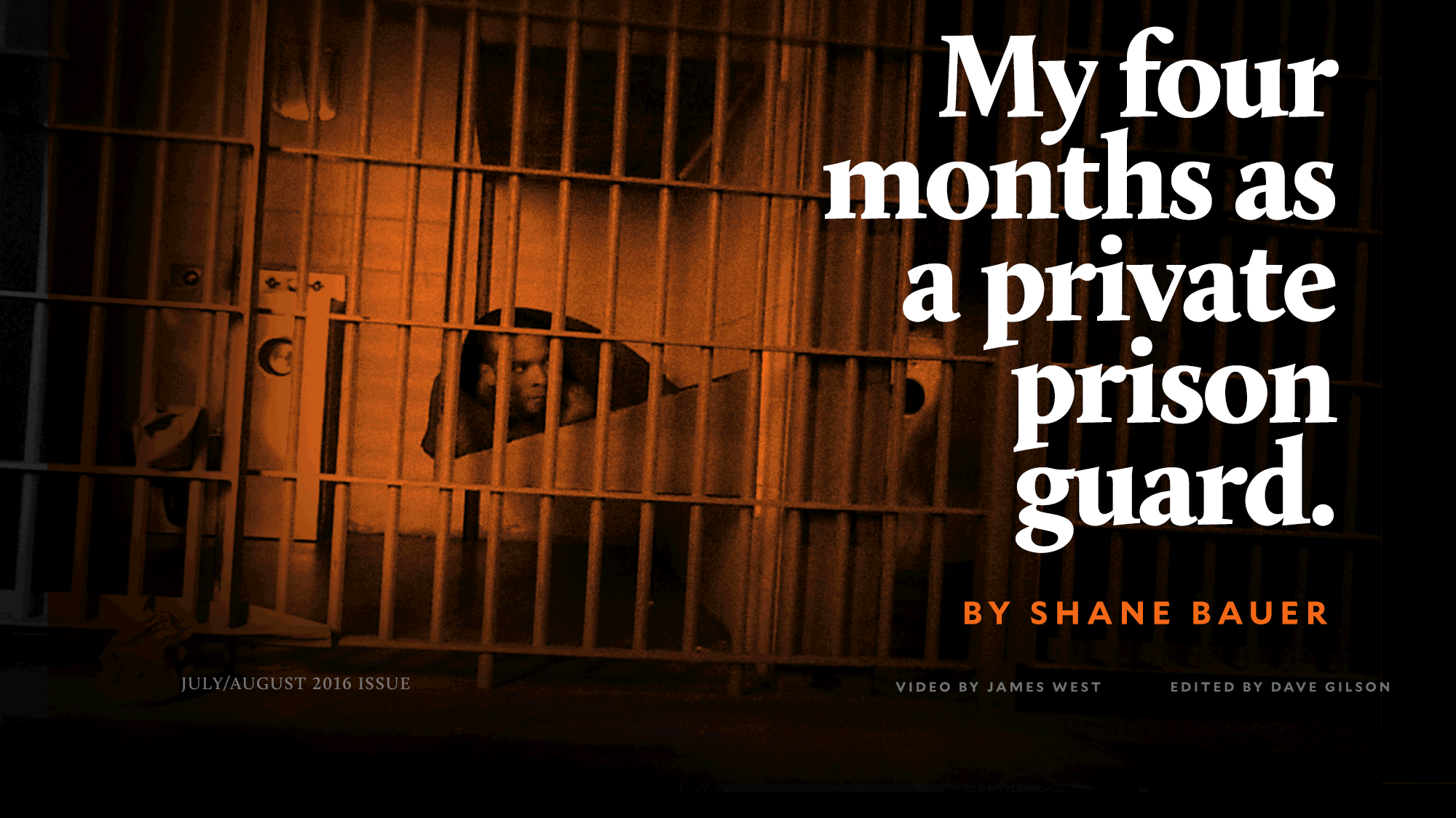

Have you ever had a riot?” I ask a recruiter from a prison run by the Corrections Corporation of America (CCA).

“The last riot we had was two years ago,” he says over the phone.

“Yeah, but that was with the Puerto Ricans!” says a woman’s voice, cutting in. “We got rid of them.”

“When can you start?” the man asks.

I tell him I need to think it over.

I take a breath. Am I really going to become a prison guard? Now that it might actually happen, it feels scary and a bit extreme.

I started applying for jobs in private prisons because I wanted to see the inner workings of an industry that holds 131,000 of the nation’s 1.6 million prisoners. As a journalist, it’s nearly impossible to get an unconstrained look inside our penal system. When prisons do let reporters in, it’s usually for carefully managed tours and monitored interviews with inmates. Private prisons are especially secretive. Their records often aren’t subject to public access laws; CCA has fought to defeat legislation that would make private prisons subject to the same disclosure rules as their public counterparts. And even if I could get uncensored information from private prison inmates, how would I verify their claims? I keep coming back to this question: Is there any other way to see what really happens inside a private prison?

CCA certainly seemed eager to give me a chance to join its team. Within two weeks of filling out its online application, using my real name and personal information, several CCA prisons contacted me, some multiple times.

They weren’t interested in the details of my résumé. They didn’t ask about my job history, my current employment with the Foundation for National Progress, the publisher of Mother Jones, or why someone who writes about criminal justice in California would want to move across the country to work in a prison. They didn’t even ask about the time I was arrested for shoplifting when I was 19.

When I call Winn Correctional Center in Winnfield, Louisiana, the HR lady who answers is chipper and has a smoky Southern voice. “I should tell you upfront that the job only pays $9 an hour, but the prison is in the middle of a national forest. Do you like to hunt and fish?”

“I like fishing.”

“Well, there is plenty of fishing, and people around here like to hunt squirrels. You ever squirrel hunt?”

“No.”

“Well, I think you’ll like Louisiana. I know it’s not a lot of money, but they say you can go from a CO to a warden in just seven years! The CEO of the company started out as a CO”—a corrections officer.

Ultimately, I choose Winn. Not only does Louisiana have the highest incarceration rate in the world—more than 800 prisoners per 100,000 residents—but Winn is the oldest privately operated medium-security prison in the country.

I phone HR and tell her I’ll take the job.

“Well, poop can stick!” she says.

I pass the background check within 24 hours.

Subscribe to our award-winning magazine today for just $12.

Two weeks later, in November 2014, having grown a goatee, pulled the plugs from my earlobes, and bought a beat-up Dodge Ram pickup, I pull into Winnfield, a hardscrabble town of 4,600 people three hours north of Baton Rouge. I drive past the former Mexican restaurant that now serves drive-thru daiquiris to people heading home from work, and down a street of collapsed wooden houses, empty except for a tethered dog. About 38 percent of households here live below the poverty line; the median household income is $25,000. Residents are proud of the fact that three governors came from Winnfield. They are less proud that the last sheriff was locked up for dealing meth.

Thirteen miles away, Winn Correctional Center lies in the middle of the Kisatchie National Forest, 600,000 acres of Southern yellow pines crosshatched with dirt roads. As I drive through the thick forest, the prison emerges from the fog. You might mistake the dull expanse of cement buildings and corrugated metal sheds for an oddly placed factory were it not for the office-park-style sign displaying CCA’s corporate logo, with the head of a bald eagle inside the “A.”

At the entrance, a guard who looks about 60, a gun on her hip, asks me to turn off my truck, open the doors, and step out. A tall, stern-faced man leads a German shepherd into the cab of my truck. My heart hammers. I tell the woman I’m a new cadet, here to start my four weeks of training. She directs me to a building just outside the prison fence.

“Have a good one, baby,” she says as I pull through the gate. I exhale.

I park, find the classroom, and sit down with five other students.

“You nervous?” a 19-year-old black guy asks me. I’ll call him Reynolds. (I’ve changed the names and nicknames of the people I met in prison unless noted otherwise.)

“A little,” I say. “You?”

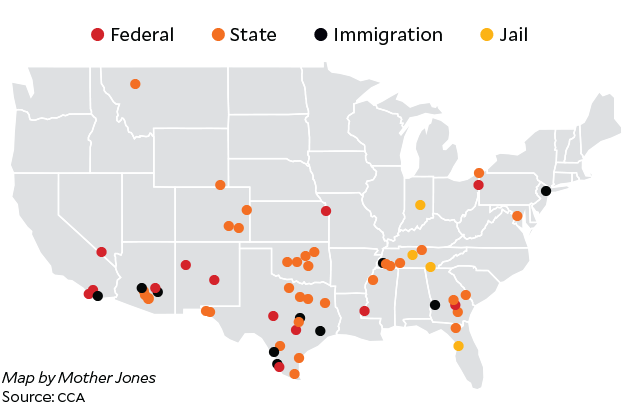

CCA RUNS 61 FACILITIES ACROSS THE UNITED STATES:

- These include 34 state prisons, 14 federal prisons, 9 immigration detention centers, and 4 jails.

- It owns 50 of these sites.

- 38 hold men, 2 hold women, 20 hold both sexes, and 1 holds women and children.**

- 17 are in Texas, 7 are in Tennessee, and 6 are in Arizona.

“Nah, I been around,” he says. “I seen killin’. My uncle killed three people. My brother been in jail, and my cousin.” He has scars on his arms. One, he says, is from a shootout in Baton Rouge. The other is from a street fight in Winnfield. He elbowed someone in the face, and the next thing he knew he got knifed from behind. “It was some gang shit.” He says he just needs a job until he starts college in a few months. He has a baby to feed. He also wants to put speakers in his truck. They told him he could work on his days off, so he’ll probably come in every day. “That will be a fat paycheck.” He puts his head down on the table and falls asleep.

The human resources director comes in and scolds Reynolds for napping. He perks up when she tells us that if we recruit a friend to work here, we’ll get 500 bucks. She gives us an assortment of other tips: Don’t eat the food given to inmates; don’t have sex with them or you could be fined $10,000 or get 10 years at hard labor; try not to get sick because we don’t get paid sick time. If we have friends or relatives incarcerated here, we need to report it. She hands out fridge magnets with the number of a hotline to use if we feel suicidal or start fighting with our families. We get three counseling sessions for free.

I studiously jot down notes as the HR director fires up a video of the company’s CEO, Damon Hininger, who tells us what a great opportunity it is to be a corrections officer at CCA. Once a guard himself, he made $3.4 million in 2015, nearly 19 times the salary of the director of the Federal Bureau of Prisons. “You may be brand new to CCA,” Hininger says, “but we need you. We need your enthusiasm. We need your bright ideas. During the academy, I felt camaraderie. I felt a little anxiety too. That is completely normal. The other thing I felt was tremendous excitement.”

I look around the room. Not one person—not the recent high school graduate, not the former Walmart manager, not the nurse, not the mother of twins who’s come back to Winn after 10 years of McDonald’s and a stint in the military—looks excited.

“I don’t think this is for me,” a postal worker says.

“Do not run!”

The next day, I wake up at 6 a.m. in my apartment in the nearby town where I decided to live to minimize my chances of running into off-duty guards. I feel a shaky, electric nervousness as I put a pen that doubles as an audio recorder into my shirt pocket.

In class that day, we learn about the use of force. A middle-aged black instructor I’ll call Mr. Tucker comes into the classroom, his black fatigues tucked into shiny black boots. He’s the head of Winn’s Special Operations Response Team, or SORT, the prison’s SWAT-like tactical unit. “If an inmate was to spit in your face, what would you do?” he asks. Some cadets say they would write him up. One woman, who has worked here for 13 years and is doing her annual retraining, says, “I would want to hit him. Depending on where the camera is, he might would get hit.”

Mr. Tucker pauses to see if anyone else has a response. “If your personality if somebody spit on you is to knock the fuck out of him, you gonna knock the fuck out of him,” he says, pacing slowly. “If a inmate hit me, I’m go’ hit his ass right back. I don’t care if the camera’s rolling. If a inmate spit on me, he’s gonna have a very bad day.” Mr. Tucker says we should call for backup in any confrontation. “If a midget spit on you, guess what? You still supposed to call for backup. You don’t supposed to ever get into a one-on-one encounter with anybody. Period. Whether you can take him or not. Hell, if you got a problem with a midget, call me. I’ll help you. Me and you can whup the hell out of him.”

He asks us what we should do if we see two inmates stabbing each other.

“I’d probably call somebody,” a cadet offers.

“I’d sit there and holler ‘stop,'” says a veteran guard.

Mr. Tucker points at her. “Damn right. That’s it. If they don’t pay attention to you, hey, there ain’t nothing else you can do.”

He cups his hands around his mouth. “Stop fighting,” he says to some invisible prisoners. “I said, ‘Stop fighting.'” His voice is nonchalant. “Y’all ain’t go’ to stop, huh?” He makes like he’s backing out of a door and slams it shut. “Leave your ass in there!”

“Somebody’s go’ win. Somebody’s go’ lose. They both might lose, but hey, did you do your job? Hell yeah!” The classroom erupts in laughter.

We could try to break up a fight if we wanted, he says, but since we won’t have pepper spray or a nightstick, he wouldn’t recommend it. “We are not going to pay you that much,” he says emphatically. “The next raise you get is not going to be much more than the one you got last time. The only thing that’s important to us is that we go home at the end of the day. Period. So if them fools want to cut each other, well, happy cutting.”

When we return from break, Mr. Tucker sets a tear gas launcher and canisters on the table. “On any given day, they can take this facility,” he says. “At chow time, there are 800 inmates and just two COs. But with just this class, we could take it back.” He passes out sheets for us to sign, stating that we volunteer to be tear-gassed. If we do not sign, he says, our training is over, which means our jobs end right here. (When I later ask CCA if its staff members are required to be exposed to tear gas, spokesman Steven Owen says no.) “Anybody have asthma?” Mr. Tucker says. “Two people had asthma in the last class and I said, ‘Okay, well, I’ma spray ’em anyway.’ Can we spray an inmate? The answer is yes.”

Five of us walk outside and stand in a row, arms linked. Mr. Tucker tests the wind with a finger and drops a tear gas cartridge. A white cloud of gas washes over us. The object is to avoid panicking, staying in the same place until the gas dissipates. My throat is suddenly on fire and my eyes seal shut. I try desperately to breathe, but I can only choke. “Do not run!” Mr. Tucker shouts at a cadet who is stumbling off blindly. I double over. I want to throw up. I hear a woman crying. My upper lip is thick with snot. When our breath starts coming back, the two women linked to me hug each other. I want to hug them too. The three of us laugh a little as tears keep pouring down our cheeks.

“Don’t ever say thank you”

Our instructors advise us to carry a notebook to keep track of everything prisoners will ask us for. I keep one in my breast pocket and jet into the bathroom periodically to jot things down. They also encourage us to invest in a watch because when we document rule infractions it is important that we record the time precisely. A few days into training, a wristwatch arrives in the mail. One of the little knobs on its side activates a recorder. On its face there is a tiny camera lens.

On the eighth day, we are pulled from CPR class and sent inside the compound to Elm—one of five single-story brick buildings where the prison’s roughly 1,500 inmates live. When we go through security, we are told to empty our pockets and remove our shoes and belts. This is intensely nerve-wracking: I send my watch, pen, employee ID, and pocket change through the X-ray machine. I walk through the metal detector and a CO runs a wand up and down my body and pats down my chest, back, arms, and legs.

The other cadets and I gather at a barred gate and an officer, looking at us through thick glass, turns a switch that opens it slowly. We pass through, and after the gate closes behind us, another opens ahead. On the other side, the CCA logo is emblazoned on the wall along with the words “Respect” and “Integrity” and a mural of two anchors inexplicably floating at sea. Another gate clangs open and our small group steps onto the main outdoor artery of the prison: “the walk.”

From above, the walk is shaped like a “T.” It is fenced in with chain-link and covered with corrugated steel. Yellow lines divide the pavement into three lanes. Clustered and nervous, we cadets travel up the middle lane from the administration building as prisoners move down their designated side lanes. I greet inmates as they pass, trying hard to appear loose and unafraid. Some say good morning. Others stop in their tracks and make a point of looking the female cadets up and down.

We walk past the squat, dull buildings that house visitation, programming, the infirmary, and a church with a wrought-iron gate shaped into the words “Freedom Chapel.” Beyond it there is a mural of a fighter jet dropping a bomb into a mountain lake, water blasting skyward, and a giant bald eagle soaring overhead, backgrounded by an American flag. At the top of the T we take a left, past the chow hall and the canteen, where inmates can buy snacks, toiletries, tobacco, music players, and batteries.

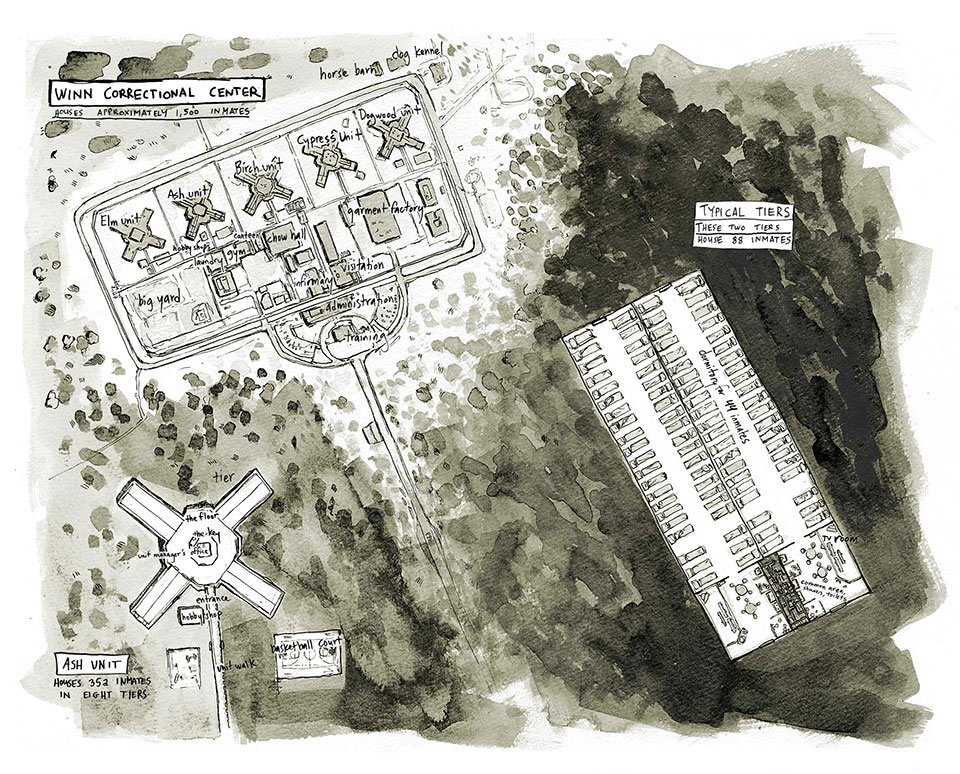

The units sit along the top of the walk. Each is shaped like an “X” and connected to the main walk by its own short, covered walk. Every unit is named after a type of tree. Most are general population units, where inmates mingle in dorm-style halls and can leave for programs and chow. Cypress is the high-security segregation unit, the only one where inmates are confined to cells.

In Dogwood, reserved for the best-behaved inmates, prisoners get special privileges like extra television time, and many work outside the unit in places like the metal shop, the garment factory, or the chow hall. Some “trusties” even get to work in the front office, or beyond the fence washing employees’ personal cars. Birch holds most of the elderly, infirm, and mentally ill inmates, though it doesn’t offer any special services. Then there are Ash and Elm, which inmates call “the projects.” The more troublesome prisoners live here.

WINN CORRECTIONAL CENTER

Medium-security prison for inmates serving 50 years or less

- Inmate population: About 1,500

- 75% black, 25% white or other

- Average inmate age: 36

- Average sentence: 19 years

- Average time served: 5.7 years

- Daily rate charged to state per inmate (2015): $34

INMATE OFFENSES

- Violent crimes: 55%

- Drug crimes: 19%

- Property crimes: 13%

- Other: 13%

We enter Elm and walk onto an open, shiny cement floor. The air is slightly sweet and musty, like the clothes of a heavy smoker. Elm can house up to 352 inmates. At the center is an enclosed octagonal control room called “the key.” Inside, a “key officer,” invariably a woman, watches the feeds of the unit’s 27-odd surveillance cameras, keeps a log of significant occurrences, and writes passes that give inmates permission to go to locations outside the unit, like school or the gym. Also in the key is the office of the unit manager, the “mini-warden” of the unit.

The key stands in the middle of “the floor.” Branching out from the floor are the four legs of the X; two tiers run down the length of each leg. Separated from the floor by a locked gate, every tier is an open dormitory that houses up to 44 men, each with his own narrow bed, thin mattress, and metal locker.

Toward the front of each tier, there are two toilets, a trough-style urinal, and two sinks. There are two showers, open except for a three-foot wall separating them from the common area. Nearby are a microwave, a telephone, and a Jpay machine, where inmates pay to download songs onto their portable players and send short, monitored emails for about 30 cents each. Each tier also has a TV room, which fills up every weekday at 12:30 p.m. for the prison’s most popular show, The Young and the Restless.

At Winn, staff and inmates alike refer to guards as “free people.” Like the prisoners, the majority of the COs at Winn are African American. More than half are women, many of them single moms. But in Ash and Elm, the floor officers—who more than anyone else deal with the inmates face-to-face—are exclusively men. Floor officers are both enforcers and a prisoner’s first point of contact if he needs something. It is their job to conduct security checks every 30 minutes, walking up and down each tier to make sure nothing is awry. Three times per 12-hour shift, all movement in the prison stops and the floor officers count the inmates. There are almost never more than two floor officers per general population unit. That’s one per 176 inmates. (CCA later tells me that the Louisiana Department of Corrections, or DOC, considered the “staffing pattern” at Winn “appropriate.”)

In Elm, a tall white CO named Christian is waiting for us with a leashed German shepherd. He tells the female cadets to go to the key and the male cadets to line up along the showers and toilets at the front of the tier. We put on latex gloves. The inmates are sitting on their beds. Two ceiling fans turn slowly. The room is filled with fluorescent light. Almost every prisoner is black.

A small group of inmates get up from their beds and file into the shower area. One, his body covered with tattoos, gets in the shower in front of me, pulls off his shirt and shorts, and hands them to me to inspect. “Do a one-finger lift, turn around, bend, squat, cough,” Christian orders. In one fluid motion, the man lifts his penis, opens his mouth, lifts his tongue, spins around with his ass facing me, squats, and coughs. He hands me his sandals and shows me the soles of his feet. I hand him his clothes and he puts his shorts on, walks past me, and nods respectfully.

Like a human assembly line, the inmates file in. “Beyend, squawt, cough,” Christian drawls. He tells one inmate to open his hand. The inmate uncurls his finger and reveals a SIM card. Christian takes it but does nothing.

Eventually, the TV room is full of prisoners. A guard looks at them and smiles. “Tear ’em up!” he says, gesturing down the tier. Each of us, women included, stops at a bed. Christian tells one cadet to “shake down bed eight real good—just because he pissed me off.” He tells us to search everything. I follow the other guards’ lead, opening bottles of toothpaste and lotion. Inside a container of Vaseline, I find a one-hitter pipe made out of a pen and ask Christian what to do with it. He takes it from me, mutters “eh,” and tosses it on the floor. I go through the mattress, pillow, dirty socks, and underwear. I flip through photos of kids, and of women posing seductively. I move on to new lockers: ramen, chips, dentures, hygiene products, peanut butter, cocoa powder, cookies, candy, salt, moldy bread, a dirty coffee cup. I find the draft of a novel, dedicated to “all the hustlers, bastards, strugglers, and hoodlum childs who are chasing their dreams.”

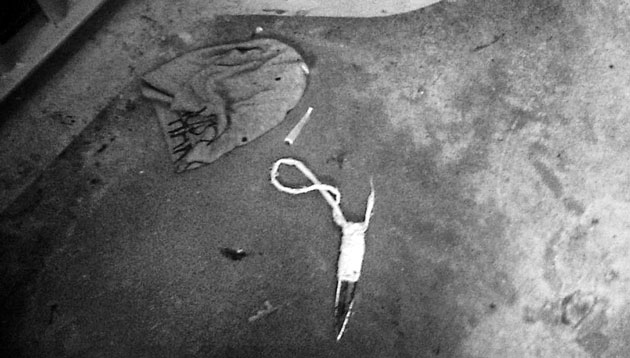

One instructor notices that I am carefully putting each object back where I found it and tells me to pull everything out of the lockers and leave it on the beds. I look down the tier and see mattresses lying on the floor, papers and food dumped across beds. The middle of the floor is strewn with contraband: USB cables refashioned as phone chargers, tubs of butter, slices of cheese, and pills. I find some hamburger patties taken from the cafeteria. A guard tells me to throw them into the pile.

Inmates are glued up against the TV room window, watching a young white cadet named Miss Stirling pick through their stuff. She’s pretty and petite, with long, jet-black hair. The attention makes her uncomfortable; she thinks the inmates are gross. Earlier this week, she said she would refuse to give an inmate CPR and won’t try the cafeteria food because she doesn’t want to “eat AIDS.” The more she is around prisoners, though, the more I notice her grapple with an inner conflict. “I don’t want to treat everyone like a criminal because I’ve done things myself,” she says.

Miss Stirling says she sometimes wonders if her baby’s dad will end up here. She doesn’t like doing chokehold escapes in class because they bring back memories of him. He cooked meth in their toolshed and once beat her so badly he dislocated her shoulder and knee. “You know that bone at the bottom of your neck? He pushed it up into my head,” she says.

Senior Reporter Shane Bauer can be reached by email at sbauer@motherjones.com.

Have a scoop for Mother Jones? Send it here.

If he ends up in this prison, another cadet assures her, “we could make his life hell.”

As we shake down the tier, a prisoner comes out of the TV room to get a better look at Miss Stirling, and she yells at him to go back in. He does.

“Thank you,” she says.

“Did she just say thank you?” Christian asks. A bunch of COs scoff.

“Don’t ever say thank you,” a woman CO tells her. “That takes the power away from it.”

“Ain’t no order here”

Most of our training is uneventful. Some days there are no more than two hours of classes, and then we have to sit and run the clock to 4:15 p.m. We pass the time discussing each other’s lives. I try mostly to stay quiet, but when I slip into describing a backpacking trip I recently took in California, a cadet throws her arms in the air and shouts, “Why are you here?!” I am careful to never lie, instead backing out with generalities like, “I came here for work,” or “You never know where life will take you,” and no one pries further.

Few of my fellow cadets have traveled farther than nearby Oklahoma. They compare towns by debating the size and quality of their Walmarts. Most are young. They eat candy during break time, write their names on the whiteboard in cutesy lettering, and talk about different ways to get high.

Miss Doucet, a stocky redheaded cadet in her late 50s, thinks that if kids were made to read the Bible in school, fewer would be in prison, but she also sticks pins in a voodoo doll to mete out vengeance. “I swing both ways,” she says. She lives in a camper with her daughter and grandkids. With this job, she’s hoping to save up for a double-wide trailer.

She worked at the lumber mill in Winnfield for years, but worsening asthma put an end to that. She’s been hospitalized several times this year and says she almost died once. “They don’t even want me to bring this in,” she whispers, leaning in, pulling her inhaler out of her pocket. “I’m not supposed to, but I do. They ain’t takin’ it away from me.” She takes a long drag from her cigarette.

Miss Doucet and others from the class ahead of mine go to the front office to get their paychecks for their first two weeks of work. When they return, the shoulders of a young cadet are slumping. He says his check was for $577, after they took $121 in taxes.

“Dang. That hurts,” he says.

Miss Doucet says they withheld $114 from her check.

“They held less for you?!” the young cadet says.

“I’m may-ried!” she says in a singsong voice. “I got a chi-ild!”

Outwardly, Miss Doucet is jovial and cocky, but she is already making mental adjustments to her dreams. The double-wide trailer she imagines her grandkids spreading out in becomes a single-wide. She figures she can get $5,000 for the RV.

CCA Facilities

At the end of one morning of doing nothing, the training coordinator tells us we can go to the gym to watch inmates graduate from trade classes. Prisoners and their families are milling around with plates of cake and cups of fruit punch. An inmate offers a piece of red velvet to Miss Stirling.

I stand around with Collinsworth, an 18-year-old cadet with a chubby white baby face hidden behind a brown beard and a wisp of bangs. Before CCA, Collinsworth worked at a Starbucks. When he came to Winnfield to help out with family, this was the first job he could get. Once, Collinsworth was nearly kicked out of class after he jokingly threatened to stab Mr. Tucker with a plastic training knife. He’s boasted to me about inmate management tactics he’s learned from seasoned officers. “You just pit ’em against each other and that’s the easiest way to get your job done,” he tells me. He says one guard told him that inmates should tell troublemakers, “‘I’m gonna rape you if you try that shit again.’ Or something; whatever it takes.”

As Collinsworth and I stand around, inmates gather to look at our watches. One, wearing a cocked gray beanie, asks to buy them. I refuse outright. Collinsworth dithers. “How old you is?” the inmate asks him.

“You never know,” Collinsworth says.

“Man, all these fake-ass signals,” the inmate says. “The best thing you could do is get to know people in the place.”

“I understand it’s your home,” Collinsworth says. “But I’m at work right now.”

“It’s your home for 12 hours a day! You trippin’. You ’bout to do half my time with me. You straight with that?”

“It’s probably true.”

“It ain’t no ‘probably true.’ If you go’ be at this bitch, you go’ do 12 hours a day.” He tells Collinsworth not to bother writing up inmates for infractions: “They ain’t payin’ you enough for that.” Seeming torn between whether to impress me or the inmate, Collinsworth says he will only write up serious offenses, like hiding drugs.

“Drugs?! Don’t worry ’bout the drugs.” The inmate says he was caught recently with two ounces of “mojo,” or synthetic marijuana, which is the drug of choice at Winn. The inmate says guards turn a blind eye to it. They “ain’t trippin’ on that shit,” he says. “I’m telling you, it ain’t that type of camp. You can’t come change things by yourself. You might as well go with the flow. Get this free-ass, easy-ass money, and go home.”

“I’m just here to do my job and take care of my family,” Collinsworth says. “I’m not gonna bring stuff in ‘cuz even if I don’t get caught, there’s always the chance that I will.”

“Nah. Ain’t no chance,” the inmate says. “I ain’t never heard of nobody movin’ good and low-key gettin’ caught. Nah. I know a dude still rolling. He been doin’ it six years.” He looks at Collinsworth. “Easy.”

The inmates’ families file out the side entrance. A couple of minutes after the last visitors leave, the coach shouts, “All inmates on the bleachers!” A prisoner tosses his graduation certificate dramatically into the trash. Another lifts the podium over his head and runs with it across the gym. The coach shouts, exasperated, as prisoners scramble around.

“You see this chaos?” the inmate in the beanie says to Collinsworth. “If you’d been to other camps, you’d see the order they got. Ain’t no order here. Inmates run this bitch, son.”

A week later, Mr. Tucker tells us to come in early to do shakedowns. The sky is barely lit as I stand on the walk at 6:30 with the other cadets. Collinsworth tells us another prisoner offered to buy his watch. He said he’d sell it for $600. The inmate declined.

“Don’t sell it to him anyway,” Miss Stirling admonishes him. “You might get $600, but if they find out, you ain’t go’ get no more paychecks.”

“Nah, I wouldn’t actually do it. I just said $600 because I know they don’t got $600 to give me.”

“Shit,” a heavyset black cadet named Willis says. He’s our main authority on prison life. He says he served seven and a half years in the Texas State Penitentiary; he won’t say what for. (CCA hires former felons whom it deems not to be a security risk; it says all Winn guards’ background checks were also reviewed by the DOC.) “Dudes was showing me pictures,” says Willis. “They got money in here. One dude in here, don’t say nothin’, but he got like six to eight thousand dollars. They got it on cards. Little money cards and shit.”

Collinsworth jumps up and down. “Dude, I’ma find me one of them damn cards! Hell yeah. And I will not report it.”

Officially, inmates are only allowed to keep money in special prison-operated accounts that can be used at the canteen. In these accounts, prisoners with jobs receive their wages, which may be as little as 2 cents an hour for a dishwasher and as much as 20 cents for a sewing-machine operator at Winn’s garment factory. Their families can also deposit money in the accounts.

The prepaid cash cards Willis is referring to are called Green Dots, and they are the currency of the illicit prison economy. Connections on the outside buy them online, then pass on the account numbers in encoded messages through the mail or during visits. Inmates with contraband cellphones can do all these transactions themselves, buying the cards and handing out strips of paper as payments for drugs or phones or whatever else.

Miss Stirling divulges that an inmate gave her the digits of a money card as a Christmas gift. “I’m like, damn! I need a new MK watch. I need a new purse. I need some new jeans.”

“There was this one dude in Dogwood,” she continues. “He came up to the bars and showed me a stack of hundred-dollar bills folded up, and it was like this—” She makes like she’s holding a wad of cash four inches thick. “And I was like, ‘I’m not go’ say anything.'”

“Dude! I’ma shake him the fuck down!” Collinsworth says. “I don’t care if he’s cool.”

“He had a phone,” Miss Stirling says, “and he’s like, ‘I don’t have the time of day to hide it. I just keep it in the open. I really don’t give a fuck.'”

Mr. Tucker tells us to follow him. We shake down tiers all morning. By the time we finish at 11, everyone is exhausted. “I’m not mad we had to do shakedowns. I’m just mad we didn’t find anything,” Collinsworth says. Christian pulls a piece of paper out of his pocket and reads off a string of numbers in a show-offy way. “A Green Dot,” he says. Christian hands the slip of paper to one of the cadets, a middle-aged white woman. “You can have this one,” he says. “I have plenty already.” She smiles coyly.

“We are going to win this unit back”

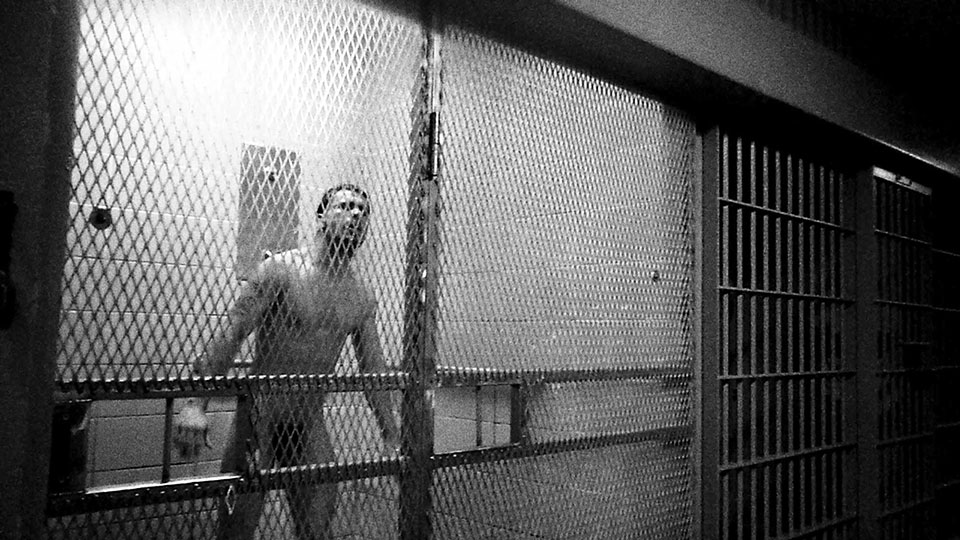

“Welcome to the hellhole,” a female CO greeted me the first time I visited the segregation unit. A few days later I’m back at Cypress with Collinsworth and Reynolds to shadow some guards. The metal door clicks open and we enter to a cacophony of shouting and pounding on metal. An alarm is sounding and the air smells strongly of smoke.

On one wall is a mural of a prison nestled among dark mountains and shrouded in storm clouds, lightning striking the guard towers and an enormous, screeching bald eagle descending with a giant pair of handcuffs in its talons. Toward the end of a long hall of cells, an officer in a black SWAT-style uniform stands ready with a pepper-ball gun. Another man in black is pulling burnt parts of a mattress out of a cell. Cypress can hold up to 200 inmates; most of the eight-by-eight-foot cells have two prisoners in them. The cells look like tombs; men lie in their bunks, wrapped in blankets, staring at the walls. Many are lit only by the light from the hallway. In one, an inmate is washing his clothes in his toilet.

“How are you doing?” says a smiling white man dressed business casual. He grips my hand. “Thank you for being here.” Assistant Warden Parker is new to CCA, but he was once the associate warden of a federal prison. “I know it seems crazy back here now, but you’ll learn the ropes,” he assures me. “We are going to win this unit back. It’s not going to happen in an hour. It’s gonna take time, but it will happen.” Apparently the segregation unit has been in a state of upheaval for a while, so corporate headquarters has sent in SORT officers from out of state to bring it back under control. SORT teams are trained to suppress riots, rescue hostages, extract inmates from their cells, and neutralize violent prisoners. They deploy an array of “less lethal” weapons like plastic buckshot, electrified shields, and chili-pepper-filled projectiles that burst on contact.

I get a whiff of feces that quickly becomes overpowering. On one of the tiers, a brown liquid oozes out of a bottle on the floor. Food, wads of paper, and garbage are all over the ground. I spot a Coke can, charred black, with a piece of cloth sticking out of it like a fuse. “I use my political voice!” an inmate shouts. “I stand up for my rights. Hahaha! Ain’t nowhere like this camp. Shit, y’all’s disorganized as fuck up in here.”

“That’s why we are here,” a SORT member says. “We are going to change all that.”

“Y’all can’t change shit,” the prisoner yells back. “They ain’t got shit for us here. We ain’t got no jobs. No rec time. We just sit in our cells all day. What you think gonna happen when a man got nuttin’ to do? That’s why we throw shit out on the tier. What else are we going to do? You know how we get these officers to respect us? We throw piss on ’em. That’s the only way. Either that or throw them to the floor. Then they respect us.”

I ask one of the regular white-shirted COs what an average day in seg looks like. “To be honest with you, normally we just sit here at this table all day long,” he tells me. They are supposed to walk up and down the eight tiers every 30 minutes to check on the inmates, but he says they never do that. (CCA says it had no knowledge of guards at Winn skipping security checks before I inquired about it.)

Collinsworth is walking around with a big smile on his face. He’s learning how to take inmates out of their cells for disciplinary court, which is inside Cypress. He’s supposed to cuff them through the slot in the bars, then tell the CO at the end of the tier to open the gate remotely. “Fuck nah, I ain’t coming out of this cell!” an inmate shouts at him. “You go’ have to get SORT to bring me up out of here. That’s how we do early in the morning. I’ll fuck y’all up.” The prisoner climbs up on the bars and pounds on the metal above the cell door. The sound explodes down the cement hallway.

Collinsworth and the CO he is shadowing move another inmate from his cell. The inmate tries to walk ahead as the CO holds him. “If that motherfucker starts pulling away from me like that again, I’m gonna make him eat concrete,” the CO says to Collinsworth.

“I kind of hope he does mess around again,” Collinsworth says, beaming. “That would be fun!”

I take a few inmates out of their cells, too, walking each one a hundred feet or so to disciplinary court with my hand around one of his elbows. One pulls against my grip. “Why you pulling on me, man?” he shouts, spinning around to stand face-to-face with me. A SORT officer rushes over and grabs him. My heart races.

Mother Jones is a nonprofit. Your support allows us to go where others in the media do not: Make a tax-deductible monthly or one-time gift.

One of the white-shirted officers takes me aside. “Hey, don’t let these guys push you around,” he says. “If he is pulling away from you, you tell him, ‘Stop resisting.’ If he doesn’t, you stop. If he keeps going, we are authorized to knee him in the back of the leg and drop him to the concrete.”

Inmates shout at me as I walk back down the tier. “He has a little twist in his walk. I like them holes in your ears, CO. Come in here with me. Give me that booty!”

At lunchtime, Collinsworth, Reynolds, and I go back to the training room. “I love it here,” Collinsworth says dreamily. “It’s like a community.”

Mother Jones is a nonprofit. Your support allows us to go where others in the media do not: Make a tax-deductible donation today.

Chapter 2: Prison Experiments

People say a lot of negative things about CCA,” the head of training, Miss Blanchard, tells us. “That we’ll hire anybody. That we are scraping the bottom of the barrel. Which is not really true, but if you come here and you breathing and you got a valid driver’s license and you willing to work, then we’re willing to hire you.” She warns us repeatedly, however, that to become corrections officers, we’ll need to pass a test at the end of our four weeks of training. We will need to know the name of the CEO, the names of the company’s founders, and their reason for establishing the first private prison more than 30 years ago. (Correct answer: “to alleviate the overcrowding in the world market.”)

To prepare us, Miss Blanchard shows a video in which CCA founders T. Don Hutto and Thomas Beasley playfully tell their company’s origin story. In 1983, they recount, they won “the first contract ever to design, build, finance, and operate a secure correctional facility in the world.” The Immigration and Naturalization Service gave them just 90 days to do it. Hutto recalls how the pair quickly converted a Houston motel into a detention center: “We opened the facility on Super Bowl Sunday the end of that January. So about 10 o’clock that night we start receiving inmates. I actually took their pictures and fingerprinted them. Several other people walked them to their ‘rooms,’ if you will, and we got our first day’s pay for 87 undocumented aliens.” Both men chuckle.

There is much about the history of CCA the video does not teach. The idea of privatizing prisons originated in the early 1980s with Beasley and fellow businessman Doctor Robert Crants. The two had no experience in corrections, so they recruited Hutto, who had been the head of Virginia’s and Arkansas’ prisons. In a 1978 ruling, the Supreme Court had found that a succession of Arkansas prison administrations, including Hutto’s, “tried to operate their prisons at a profit.” Guards on horseback herded the inmates, who sometimes did not have shoes, to the fields. The year after Hutto joined CCA, he became the head of the American Correctional Association, the largest prison association in the world.

To Beasley, the former chairman of the Tennessee Republican Party, the business of private prisons was simple: “You just sell it like you were selling cars, or real estate, or hamburgers,” he told Inc. magazine in 1988. Beasley and Crants ran the business a lot like a hotel chain, charging the government a daily rate for each inmate. Early investors included Sodexho-Marriott and the venture capitalist Jack Massey, who helped build Kentucky Fried Chicken, Wendy’s, and the Hospital Corporation of America.

The 1980s were a good time to get into the incarceration business. The prison population was skyrocketing, the drug war was heating up, the length of sentences was increasing, and states were starting to mandate that prisoners serve at least 85 percent of their terms. Between 1980 and 1990, state spending on prisons quadrupled, but it wasn’t enough. Prisons in many states were filled beyond capacity. When a federal court declared in 1985 that Tennessee’s overcrowded prisons violated the Eighth Amendment’s ban on cruel and unusual punishment, CCA made an audacious proposal to take over the state’s entire prison system. The bid was unsuccessful, but it planted an idea in the minds of politicians across the country: They could outsource prison management and save money in the process. Privatization also gave states a way to quickly expand their prison systems without taking on new debt. In the perfect marriage of fiscal and tough-on-crime conservatism, the companies would fund and construct new lockups while the courts would keep them full.

Private and public prison populations, 1990-2014

When CCA shares appeared on the NASDAQ stock exchange in 1986, the company was operating two juvenile detention centers and two immigrant detention centers. Today, it runs more than 60 facilities, from state prisons and jails to federal immigration detention centers. All together, CCA houses at least 66,000 inmates at any given time. Its main competitor, the GEO Group, holds more than 70,000 inmates in the United States. Currently, private prisons oversee about 8 percent of the country’s total prison population.

Whatever taxpayer money CCA receives has to cover the cost of housing, feeding, and rehabilitating inmates. While I work at Winn, CCA receives about $34 per inmate per day. In comparison, the average daily cost per inmate at the state’s publicly run prisons is about $52. Some states pay CCA as much as $80 per prisoner per day. In 2015, CCA reported $1.9 billion in revenue; it made more than $221 million in net income—more than $3,300 for each prisoner in its care. CCA and other prison companies have written “occupancy guarantees” into their contracts, requiring states to pay a fee if they cannot provide a certain number of inmates. Two-thirds of the private-prison contracts recently reviewed by the anti-privatization group In the Public Interest had these prisoner quotas. Under CCA’s contract, Winn was guaranteed to be 96 percent full.

The main argument in favor of private prisons—that they save taxpayers money—remains controversial. One study estimated that private prisons cost 15 percent less than public ones; another found that public prisons were 14 percent cheaper. After reviewing these competing claims, researchers concluded that the savings “appear minimal.” CCA directed me to a 2013 report—funded in part by the company and GEO—that claimed private prisons could save states as much as 59 percent over public prisons without sacrificing quality.

Private prisons’ cost savings are “modest,” according to one Justice Department study, and are achieved mostly through “moderate reductions in staffing patterns, fringe benefits, and other labor-related costs.” Wages and benefits account for 59 percent of CCA’s operating expenses. When I start at Winn, nonranking guards make $9 an hour, no matter how long they’ve worked there. The starting pay for guards at public state prisons comes out to $12.50 an hour. CCA told me that it “set[s] salaries based on the prevailing wages in local markets,” adding that “the wages we provided in Winn Parish were competitive for that area.”

Based on data from Louisiana’s budget office, the cost per prisoner at Winn, adjusted for inflation, dropped nearly 20 percent between the late ’90s and 2014. The pressure to squeeze the most out of every penny at Winn seems evident not only in our paychecks, but in decisions that keep staffing and staff-intensive programming for inmates at the barest of levels. When I asked CCA about the frequent criticism I heard from both staff and inmates about its relentless focus on the bottom line, its spokesman dismissed the assertion as “a cookie-cutter complaint,” adding that it would be false “to claim that CCA prioritizes its own economic gain over the needs of its customers” or the safety of its inmates.

The escape

Two weeks after I start training, Chase Cortez (his real name) decides he has had enough of Winn. It’s been nearly three years since he was locked up for theft, and he has only three months to go. But in the middle of a cool, sunny December day, he climbs onto the roof of Birch unit. He lies down and waits for the patrol vehicle to pass along the perimeter. He is in view of the guard towers, but they’ve been unmanned since at least 2010. Now, a single CO watches the video feeds from at least 30 cameras.

Cortez sees the patrol van pass, jumps down from the back side of the building, climbs the razor-wire perimeter fence, and then makes a run for the forest. He fumbles through the dense foliage until he spots a white pickup truck left by a hunter. Lucky for him, it is unlocked, with the key in the ignition.

In the control room, an alarm sounds, indicating that someone has touched the outer fence, a possible sign of a perimeter breach. The officer reaches over, switches the alarm off, and goes back to whatever she was doing. She notices nothing on the video screen, and she does not review the footage. Hours pass before the staff realizes someone is missing. Some guards tell me it was an inmate who finally brought the escape to their attention. Cortez is caught that evening after the sheriff chases him and he crashes the truck into a fence.

When I come in the next morning, the prison is on lockdown. Staff are worried CCA is going to lose its contract with Louisiana. “We were already in the red, and this just added to it,” the assistant training director tells me. “It’s a lot of tension right now.”

CCA said nothing publicly about the escape; I heard about it from guards who had investigated the incident or been briefed by the warden. (The company later told me it conducted a “full review” of the incident and fired a staff member “for lack of proper response to the alarm.” When I asked CCA about its decision to remove guards from Winn’s watchtowers, its spokesman replied that “newer technologies…are making guard towers largely obsolete.”)

Later that day, Reynolds and I bring food to Cypress, the segregation unit. It is dinnertime, but inmates haven’t had lunch yet. A naked man is shouting frantically for food, mercilessly slapping the plexiglass at the front of his cell. In the cell next to him, a small, wiry man is squatting on the floor in his underwear. His arms and face are scraped with little cuts. A guard tells me to watch him.

It is Cortez. I offer him a packet of Kool-Aid in a foam cup. He says thank you, then asks if I will put water in it. There is no water in his cell.

When inmates are written up for breaking the rules, they are sent to inmate court, which is held in a room in the corner of Cypress unit. One day, our class files into the small room to watch the hearings. Miss Lawson, the assistant chief of security, is acting as the judge, sitting at a desk in front of a mural of the scales of justice. “Even though we treat every inmate like they are guilty until proven innocent, they are…?” She pauses for someone to fill in the answer.

“Innocent?” a cadet offers.

“That’s right. Innocent until proven guilty.”

This is not a court of law, although it issues punishments for felonies such as assault and attempted murder. An inmate who stabs another may end up facing new criminal charges. He may be transferred, yet prisoners and guards say inmates who stab others typically are not shipped to a higher-security prison. The consequences for less serious offenses are usually stints in seg or a loss of “good time,” sentence reduction for good behavior. According to the DOC, Winn inmates charged with serious rule violations are found guilty at least 96 percent of the time.

“Inmate counsel, has your defendant appeared before the court?” Miss Lawson asks a prisoner standing at the podium.

“No, ma’am, he has not,” he replies. The inmate counsel represents other inmates in the internal disciplinary process. Every year, he is taken to a state-run prison for intensive training. Miss Lawson later tells me that inmate counsel never really influences her decisions.

The absent inmate is accused of coming too close to the main entrance. “Would the counsel like to offer a defense?”

“No, ma’am.”

“How does he plead?”

“Not guilty.”

“Mr. Trahan is found guilty.” The entire “trial” lasts less than two minutes.

The next defendant is called.

He is being considered for release from segregation. “Do you know your Bible?” Miss Lawson asks.

“Yes, ma’am.”

“Do you remember in the Gospel of John when the adulteress was brought before Jesus? What did he say?”

“I don’t remember that, ma’am.”

“He says, ‘Sin no more.'” She points for him to leave the room.

The next inmate, an orderly in Cypress, enters. He is charged with being in an unauthorized area because he took a broom to sweep the tier during rec time, which is not the authorized time to sweep the tier. He starts to explain that a CO gave him permission. Miss Lawson cuts him off. “How would you like to plead?”

“Guilty, I guess.”

“You are found guilty and sentenced to 30 days’ loss of good time.”

“Man! Y’all—this is fucked up, man. Y’all gonna take my good time!?” He runs out of the room. “They done took my good time!” he screams in the hall. “They took my good time! Fuck them!” For removing a broom from a closet at the wrong time, this inmate will stay in prison an extra 30 days, for which CCA will be paid more than $1,000.

True colors

One day in class we take a personality test called True Colors that’s supposed to help CCA decide how to place us. Impulsive “orange” people can be useful in hostage negotiations because they don’t waste time deliberating. Rule-oriented “gold” people are chosen for the daily management of inmates. The majority of the staff, Miss Blanchard says, are gold—dutiful, punctual people who value rules. My results show that green is my dominant color (analytical, curious) and orange is my secondary (free and spontaneous). Green is a rare personality type at Winn. Miss Blanchard doesn’t offer any examples of how greens can be useful in a prison.

The company that markets the test claims that people who retake it get the same results 94 percent of the time. But Miss Blanchard says that after working here awhile, people often find their colors have shifted. Gold traits tend to become more dominant.

Studies have shown that personalities can change dramatically when people find themselves in prison environments. In 1971, psychologist Philip Zimbardo conducted the now-famous Stanford Prison Experiment, in which he randomly assigned college students to the roles of prisoners and guards in a makeshift basement “prison.” The experiment was intended to study how people respond to authority, but it quickly became clear that some of the most profound changes were happening to the guards. Some became sadistic, forcing the prisoners to sleep on concrete, sing and dance, defecate into buckets, and strip naked. The situation became so extreme that the two-week study was cut short after just six days. When it was over, many “guards” were ashamed at what they had done and some “prisoners” were traumatized for years. “We all want to believe in our inner power, our sense of personal agency, to resist external situational forces of the kinds operating in this Stanford Prison Experiment,” Zimbardo reflected. “For many, that belief of personal power to resist powerful situational and systemic forces is little more than a reassuring illusion of invulnerability.”

The question the study posed still lingers: Are the soldiers of Abu Ghraib, or even Auschwitz guards and ISIS hostage-takers, inherently different from you and me? We take comfort in the notion of an unbridgeable gulf between good and evil, but maybe we should understand, as Zimbardo’s work suggested, that evil is incremental—something we are all capable of, given the right circumstances.

One day during our third week of training I am assigned to work in the chow hall. My job is to tell the inmates where to sit, filling up one row of tables at a time. I don’t understand why we do this. “When you fill up this side, start clearing them out,” the captain tells me. “They get 10 minutes to eat.” CCA policy is 20 minutes. We just learned that in class.

Inmates file through the chow line and I point them to their tables. One man sits at the table next to the one I directed him to. “Right here,” I say, pointing to the table again. He doesn’t move. The supervisor is watching. Hundreds of inmates can see me.

“Hey. Move back to this table.”

“Hell nah,” he says. “I ain’t movin’.”

“Yes, you are,” I say. “Move.” He doesn’t.

I get the muscle-bound captain, who comes and tells the inmate to do what I say. The inmate gets up and sits at a third table. He’s playing with me. “I told you to move to that table,” I say sternly.

“Man, the fuck is this?” he says, sitting at the table I point to. I’m shaky with fear. Project confidence. Project power. I stand tall, broaden my shoulders, and stride up and down the floor, making enough eye contact with people to show I’m not intimidated, but not holding it long enough to threaten them. I tell inmates to take off their hats as they enter. They listen to me, and a part of me likes that.

For the first time, for just a moment, I forget that I am a journalist. I watch for guys sitting with their friends rather than where they are told to. I scan the room for people sneaking back in line for more food. I tell inmates to get up and leave while they are still eating. I look closely to make sure no one has an extra cup of Kool-Aid.

“Hey, man, why you gotta be a cop like that?” asks the inmate whom I moved. “They don’t pay you enough to be no cop.”

“Hey Bauer, go tell that guy to take his hat off,” Collinsworth says, pointing to another inmate. “I told him and he didn’t listen to me.”

“You tell him,” I say. “If you’re going to start something, you got to finish it.” A CO looks at me approvingly.

The dog team

Out in the back of the prison, not far from where Chase Cortez hopped the fence, there is a barn. Miss Blanchard, another cadet, and I step inside the barn office. Country music is playing on the radio. Halters, leashes, and horseshoes hang on the walls. Three heavyset white COs are inside. They do not like surprise visits. One spits into a garbage can.

The men and their inmate trusties take care of a small herd of horses and three packs of bloodhounds. The horses don’t do much these days. The COs used to mount them with shotguns and oversee hundreds of inmates who left the compound every day to tend the grounds. The shotguns had to be put to use when, occasionally, an inmate tried to run for it. “You don’t actually shoot to kill; you shoot to stop,” a longtime staff member told me one day. “Oops! I killed him,” she said sarcastically. “I told him to stop! We can always get another inmate, though.”

Prisoners and officers alike talk nostalgically about the time when the men spent their days working outside, coming back to their dorms drained of restless energy and aggression. CCA’s contract requires that Winn inmates are assigned to “productive full time activity” five days a week, but few are. The work program was dropped around the same time that guards were taken out of the towers. Many vocational programs at Winn have been axed. The hobby shops have become storage units; access to the law library is limited. The big recreation yard sits empty most of the time: There aren’t enough guards to watch over it. (Asked about the lack of classes, recreation, and other activities at Winn, CCA insisted “these resources and programs were largely available to inmates.” It said the work program was cut during contract negotiations with the DOC, and it acknowledged some gaps in programming due to “brief periods of staffing vacancies.”)

“Things ain’t like they used to be,” Chris, the officer who runs the dog team, tells us. “It’s a frickin’ mess.”

“Can’t whup people’s ass like we used to,” another officer named Gary says.

“Yeah you can! We did!” Chris says. He then sulks a little: “You got to know how to do it, I guess.”

“You got to know where to do it also,” Miss Blanchard says, referring, I assume, to the areas of the prison the cameras don’t see.

“We got one in the infirmary,” Chris says. “Haha! Gary gassed him.”

“You always using the gas, man,” the third officer says.

“If one causes me to do three or four hours of paperwork, I’m go’ put somethin’ on his ass,” Gary says. “He’s go’ get some gas. He’s go’ get the full load. I ain’t go’ do just a light use of force on him; I’m go’ handle my business with him. Of course, y’all the new class. I’m sitting here telling y’all wrong. Do it the right way. But sometimes, you just can’t do it the right way.”

With no work program to oversee, the men’s main job is to take the horses and the packs of bloodhounds anywhere across 13 nearby parishes to help the police chase down suspects or prison escapees. They’ve apprehended armed robbers and murder suspects.

When we step inside the kennel, the bloodhounds bay and howl. Gary kicks the door of one cage and a dog lunges at his foot. “If they can get to him, they go’ to bite him,” he says. “They deal with ’em pretty bad.”

Back in the barn office, Gary pulls a binder off the shelf and shows us a photo of a man’s face. There is a red hole under his chin and a gash down his throat. “I turn inmates loose every day and go catch ’em,” Chris says, rubbing the stubble on his neck. “And that was the result to one of ’em.”

“A dog, when he got too close to him, bit him in the throat,” Gary says.

“That’s an inmate?” I ask.

“Yeah. What we’ll do is we’ll take a trusty and we’ll put him in them woods right out there.” He points out the window. The trusty wears a “bite suit” to protect him from the dogs. “We’ll tell him where to go. He might walk back here two miles. We’ll tell him what tree to go up, and he goes up a tree.” Then, after some time passes, they “turn the dogs loose.”

He holds up the picture of the guy with the throat bite. “This guy here, he got too close to ’em.” Christian walks in the door.

“That looks nasty,” I say.

“Eh, it wasn’t that bad,” Christian cuts in. “I took him to the hospital. It wasn’t that bad.” (CCA says the inmate’s injuries were “minor.”)

Gary, still holding out the picture, says, “He was a character.”

“He was a piece of crap,” Christian says. “Instigator.”

“I gave him his gear and he didn’t put it on correctly. That’s on him,” Chris says with a shrug.

“Part of the bid’ness”

“I would kill an inmate if I had to,” Collinsworth says to me during a break one day. We are standing around outside; most cadets are smoking cigarettes. “I wouldn’t feel bad about it, not if they were attacking me.”

“You got to feel some kinda remorse if you a human being,” Willis says.

“I can’t see why you’d need to kill anyone,” Miss Stirling says.

“You might have to,” says Collinsworth.

“I do what needs to get done,” says a fortysomething, chubby-faced white officer. He wears a baseball cap low over his eyes. “I just had a use of force on an inmate who just got out of open-heart surgery. It’s all part a the bid’ness.” (CCA says it cannot confirm this incident.)

The officer’s name is Kenny. He’s been working here for 12 years, and he views inmates as “customers.” While teaching class, he lectures us on CCA’s principle of “cost-effectiveness,” which requires us to “provide honest and fair, competitive pricing to our partner and deliver value to our shareholders.” A part of being cost-effective is not getting sued too often. “One thing the Department of Corrections does is they give us a certain amount of money to manage this facility,” Kenny explains. “They set a portion of money back for lawsuits, but if we go over budget, it’s kind of like any other job. We got 60-something-plus facilities. If they not making no money at Winn Correctional Center, guess what? We not go’ be employed.”

Kenny is detached and cool. He says he used to have a temper but he’s learned to control it. He doesn’t sit in bed at night writing up disciplinary reports while his wife sleeps, like he did years ago. Now, if an inmate gives him a smart mouth or doesn’t keep a tidy bed, he’ll throw him in seg to set an example. There are rules, and they are meant to be followed. This goes both ways: When he has any say, he makes sure inmates get what they are entitled to. He prides himself on his fairness. “All them inmates ain’t bad,” he reminds us. Everyone deserves a chance at redemption.

Still, we must never let inmates forget their place. “When you a inmate and you talk too much and you think you free, it’s time for you to go,” he says. “You got some of these guys, they smart. They real educated. I know one and I be talkin’ to him and he smarter than me. Now he might have more book sense, but he ain’t got more common sense. He go’ talk to me at a inmate level, not at no staff level. You got to put ’em in check sometimes.”

Kenny makes me nervous. He notices that I am the only one in class who takes notes. One day, he tells us that he sits on the hiring committee. “We don’t know what you here for,” he says to the class. He then glances at me. “There might be somebody in this room here hooked up wit’ a inmate.” Throughout the day, he asks my name on several occasions. “My job is to monitor inmates; it’s also to monitor staff. I’m a sneaky junker.” He turns and looks me directly in the eyes. “I come up here and tell you I don’t know what your name is? I know what your name is. That’s just a game I’m playing with you.” I feel my face flush. I chuckle nervously. He has to know. “I play games just like they play games. I test my staff to test their loyalty. I report to the warden about what I see. It’s a game, but it’s also a part of the bid’ness.”

Mail call

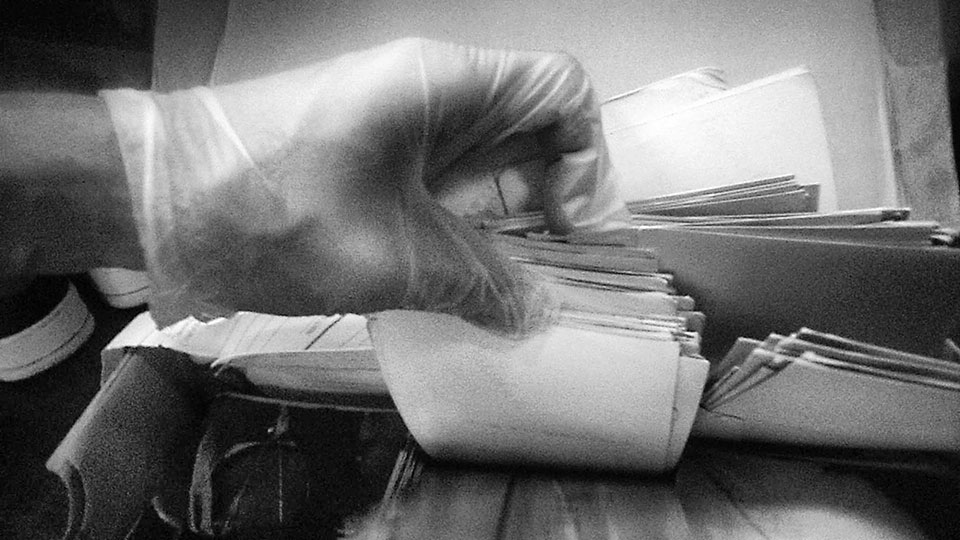

Over Christmas week, I am stationed in the mail room with a couple of other cadets to process the deluge of holiday letters. The woman in charge, Miss Roberts, demonstrates our task: Slice the top of each envelope, cut the back off and throw it in the trash, cut the postage off the front, staple what remains to the letter, and stamp it: Inspected.

Miss Roberts opens a letter with several pages of colorful child’s drawings. “Now, see like this one, it’s not allowed because they’re not allowed to get anything that’s crayon,” she says. I presume this is for the same reason we remove stamps; crayon could be a vehicle for drugs. There are so many letters from children—little hands outlined, little stockings glued to the inside of cards—that we rip out and throw in the trash.

One reads:

I love you and miss you so much daddy, but we are doing good. Rick Jr. is bad now. He gets into everything. I have not forgot you daddy. I love you.

Around the mail room, there are bulletins posted of things to look out for: an anti-imperialist newsletter called Under Lock and Key, an issue of Forbes that comes with a miniature wireless internet router, a CD from a Chicano gangster rapper with a track titled “Death on a CO.” I find a list of books and periodicals that aren’t allowed inside Louisiana prisons. It includes Fifty Shades of Grey; Lady Gaga Extreme Style; Surrealism and the Occult; Tai Chi Fa Jin: Advanced Techniques for Discharging Chi Energy; The Complete Book of Zen; Socialism vs Anarchism: a Debate; and Native American Crafts & Skills. On Miss Roberts’ desk is a confiscated book: Robert Greene’s 48 Laws of Power, a self-help book favored by 50 Cent and Donald Trump. Other than holy books, this is the most common text I see in inmates’ lockers, usually tattered and hidden under piles of clothes. She says this book is banned because it’s considered “mind-bending material,” though she did enjoy it herself. There are also titles on the list about black history and culture, like Huey: Spirit of the Panther; Faces of Africa; Message to the Blackman in America, by Elijah Muhammad; and an anthology of news articles called 100 Years of Lynchings.

“That’s the craziest girl I ever seen,” Miss Roberts says of the woman who wrote the letter she holds in her hand. She is familiar with many of the correspondents from reading about the intimate details of their lives. “She’s got his whole name tattooed across her back, all the way down to her hip bone. When his ass gets out—whenever he gets out, ‘cuz he’s got 30 or 40 years—if he ever gets out, he ain’t going to her.”

I feel like a voyeur, but the letters draw me in. I am surprised at how many are from former inmates with lovers still at Winn. I read one from a man currently incarcerated in Angola, Louisiana’s infamous maximum-security prison:

Our anniversary is in 13 more days on Christmas and we could have been married for 2 years why can’t you see that I want this to work between us?…Bae, [remember] the tattoo on my left tittie close to my heart that won’t never get covered up as long as I have a breath in my body and I‘m about to get your name again on my ass cheek.

Another is from a recently released inmate to his lover:

Hope everything is going well with you. Very deeply in love with you…

I won’t be able to spend x-mass with my family either. Baby my heart is broken and I am so unhappy. I always had a great fear of being homeless…And even if I did find a job and had to work nights or work the evening shift, then I wouldn’t have anywhere to sleep because the shelter won’t let you in to sleep after hours. In order to get my bed every night I have to check in before 4pm. After that you lose your bed so the program is designed to keep you homeless. It don’t make sense…

I bet that this is a sad letter. I wish that I had good news. This will be a short letter because I don’t have a lot of paper left.

Merry Christmas baby. Very deeply in love with you.

The front of one card reads, “Although your situation may seem impossible…” and continues on the inside, “through Christ, all things are Him-possible!” It contains a letter from the wife of an inmate:

Here I am once again w/ thoughts of you. I hate it here everything reminds me of you. I miss u dammit! It’s weird this connection we have its as if I carry you in my soul. It terrifies me the thought of ever losing you. I pray you haven’t replaced me. I know I haven’t been the most supporting but baby seriously you don’t know the hell I’ve been through since we got torn apart And I guess my family got fed up w/ seeing me kill myself slowly I attempted twice 90 phenobarb 2 roxy 3 subs. I lived. 2nd after I hung up w/ you 60 Doxepin 90 propananol i lived WTF? God has a sense of humor i don’t have anyone but u, u see no one cares whether I live die hurt am hungry, well, or safe…So I’ve been alone left to struggle to survive on my income in and out mental wards and running from the pain of you bein there…

Your my everything always will be

Love your wife.

This note and its list of pills haunt me all weekend. What if no one else knows this woman tried to commit suicide? I decide I need to tell Miss Roberts, but when I return to work, I sit in the parking lot and have a hard time summoning the courage. What if word gets out that I’m soft, not cut out for this work?

After I pass through the scanner, I see her. “Hey, Miss Roberts?” I say, walking up behind her.

“Yes,” she says sweetly.

“I wanted to check with you about something. I meant to do it on Friday, but, uh…” She stops and gives me her full attention, looking me in the eyes. “When we had a class by the mental health director, she told us to report if there was any kind of suicidal—”

She cuts me off, waving her hand dismissively, and starts walking away.

“No, but it was like a letter thing—”

“Yeah, don’t even worry about that,” she says, still walking toward her door.

“Really?”

“Mmmhmmm. That’s if you see something going on down there,” she says, pointing toward the units. “Yeah, don’t worry about it. All right.” She enters the mail room.

We can go after stories that no one else will, thanks to our donors. Underwrite our reporting with a tax-deductible monthly or one-time gift.

We can go after stories that no one else will, thanks to readers like you. Underwrite our reporting with a tax-deductible gift.

After Christmas, we take our final test. It is intimidating. The test was created by CCA; we never take the qualification exam given to the state’s guards. Ninety-two questions ask us about the chain of command, the use-of-force policy, what to do if we are taken hostage, how to spot a suicidal inmate, the proper way to put on leg irons, the color designation for various chemical agents. We went through most of these topics so cursorily there’s no way I could answer half of them. Luckily, I don’t need to worry. The head of training’s assistant tells us we can go over the test together to make sure we get everything right.

“I bet no one ever doesn’t get the job because they fail the test,” I say.

“No,” she says. “We make sure your file looks good.” (CCA says this was not consistent with its practices.)

About a third of the trainees I started with have already quit. Reynolds is gone. Miss Doucet decides she can’t risk an asthma attack, so she quits too. Collinsworth goes to Ash on the night shift. Willis works the night shift too; he will be fired after he leaves the prison suddenly one day and a bunch of cellphones are found at his post. Miss Stirling gets stationed in Birch on the day shift. She won’t last either. Two and a half months from now, she will be escorted from the prison for smuggling contraband and writing love letters to an inmate.

Chapter 3: “The CCA Way”

It’s the end of December, and I come in at 6 a.m. for my first of three days of on-the-job training, the final step before I become a full-fledged CO. The captain tells an officer to take me to Elm. We move slowly down the walk. “One word of advice I would give you is never take this job home with you,” he says. He spits some tobacco through the fence. “Leave it at the front gate. If you don’t drink, it’ll drive you to drinking.”

Research shows that corrections officers experience above-average rates of job-related stress and burnout. Thirty-four percent of prison guards suffer from post-traumatic stress disorder, according to a study by a nonprofit that researches “corrections fatigue.” That’s a higher rate than reported by soldiers returning from Iraq and Afghanistan. COs commit suicide two and a half times more often than the population at large. They also have shorter life spans. A recent study of Florida prison guards and law enforcement officers found that they die 12 years earlier than the general population; one suggested cause was job-related stress.

The walk is eerily quiet. Crows caw, fog hangs low over the basketball courts. The prison is locked down. Programs have been canceled. With the exception of kitchen workers, none of the inmates can leave their dorms. Usually, lockdowns occur when there are major disturbances, but today, with some officers out for the holidays, guards say there just aren’t enough people to run the prison. (CCA says Winn was never put on lockdown due to staffing shortages.) The unit manager tells me to shadow one of the two floor officers, a burly white Marine veteran. His name is Jefferson, and as we walk the floor an inmate asks him what the lockdown is about. “You know half of the fucking people don’t want to work here,” Jefferson tells him. “We so short-staffed and shit, so most of the gates ain’t got officers.” He sighs dramatically. (CCA claims to have “no knowledge” of gates going unmanned at Winn.)

“It’s messed up,” the prisoner says.

“Man, it’s so fucked up it’s pitiful,” Jefferson replies. “The first thing the warden asked me [was] what would boost morale around here. The first two words out of my mouth: pay raise.” He takes a gulp of coffee from his travel mug.

“They do need to give y’all a pay raise,” the prisoner says.

“When gas is damn near $4 a gallon, what the fuck is $9 an hour?” Jefferson says. “That’s half yo’ check fillin’ up your gas!”

Another inmate, whom Jefferson calls “the unit politician,” demands an Administrative Remedy Procedure form. He wants to file a grievance about the lockdown—why are inmates being punished for the prison’s mismanagement?

“What happens to those ARPs?” I ask Jefferson.

“If they feel their rights have been violated in some way, they are allowed to file a grievance,” he says. If the captain rejects it, they can appeal to the warden. If the warden rejects it, they can appeal to the Department of Corrections. “It’ll take about a year,” he says. “Once it gets to DOC down in Baton Rouge, they throw it over in a pile and forget about it. I’ve been to DOC headquarters. I know what them sonsabitches do down there: nothin’.” (Miss Lawson, the assistant chief of security, later tells me that during the 15 years she worked at Winn, she saw only one grievance result in consequences for staff. )

I do a couple of laps around the unit floor and then see Jefferson leaning against the threshold of an open tier door, chatting with a prisoner. I walk over to them. “This your first day?” the prisoner asks me, leaning up against the bars.

“Yeah.”

“Welcome to CCA, boy. You seen what the sign say when you first come in the gate? It says, ‘The CCA Way.’ Know what that is?” he asks me. There is a pause. “Whatever way you make it, my boy.”

Jefferson titters. “Some of them down here are good,” he says. “I will say dat. Some of ’em are jackasses. Some of ’em just flat-out ain’t worth a fuck.”

“Just know at the end of the day, how y’all conduct y’all selves determines how we conduct ourselves,” the prisoner says to me. “You come wit’ a shit attitude, we go’ have a shit attitude.”

“I have three rules and they know it,” Jefferson says as he grips the bars with one hand. “No fightin’. No fuckin’. No jackin’ off. But! What they do after the lights are out? I don’t give a fuck, ‘cuz I’m at the house.”

The next day, I’m stationed in Ash, a general population unit. The unit manager is a black woman who is so large she has trouble walking. She is brought in every morning in a wheelchair pushed by an inmate. Her name is Miss Price, but inmates call her The Dragon. It’s unclear whether her jowls, her roar, or her stern reputation earned her that name. Prisoners relate to her like an overbearing mother, afraid to anger her and eager to win her affection. She’s worked here since the prison opened in 1991, and one CO says that in her younger days, she was known to break up fights without backup. Another CO says that last week an inmate “whipped his thing out and was playing with himself right in front of her. She got out of her wheelchair, grabbed him by the neck, threw him up against the wall. She said, ‘Don’t you ever fucking do that to me again!'”

In the middle of the morning, Miss Price tells us to shake down the common areas. I follow one of the two COs into a tier and we do perfunctory searches of the TV room and tables, feeling under the ledges, flipping through a few books. I bend over and feel around under a water fountain. My hand lands on something loose. I get on my knees to look. It’s a smartphone. I don’t know what to do—do I take it or leave it? My job, of course, is to take it, but by now I know that being a guard is only partially about enforcing the rules. Mostly, it’s about learning how to get through the day safely, which requires decisions like these to be weighed carefully.

A prisoner is watching me. If I leave the phone, everyone on the tier will know. I will win inmates’ respect. But if I take it, I will show my superiors I am doing my job. I will alleviate some of the suspicion they have of every new hire. “Those ones who gets along with ’em—those ones are the ones I really have to watch,” SORT commander Tucker told us in class. “There is five of y’all. Two and a half are gonna be dirty.”

I take the phone.

Miss Price is thrilled. The captain calls the unit to congratulate me. The other COs couldn’t care less. When I do count later, each inmate on that tier stares at me with his meanest look. Some step toward me threateningly as I pass.

Later, at a bar near my apartment, I see a man in a CCA jacket and ask him if he works at Winn. “Used to,” he says.

“I just started there,” I say.

He smiles. “Let me tell you this: You ain’t go’ like it. When you start working those 12-hour shifts, you will see.” He takes a drag from his cigarette. “The job is way too fucking dangerous.” I tell him about the phone. “Oh, they won’t forget your face,” he says. “I just want you to know you made a lot of enemies. If you work in Ash, you gonna have a big-ass problem because now they go’ know, he’s gonna be the guy who busts us all the time.”

He racks the balls on the pool table and tells me about a nurse who gave a penicillin shot to an inmate who was allergic to the medicine and died. The prisoner’s friends thought the nurse did it intentionally. “When he came down the walk, they beat the shit out of him. They had to airlift him out of there.” (CCA says it has no knowledge of this incident.) He breaks and sinks a stripe.

Suicide watch

On my first official day as a CO, I am stationed on suicide watch in Cypress. In the entire prison of more than 1,500 inmates, there are no full-time psychiatrists and just one full-time social worker: Miss Carter. In class, she told us that a third of the inmates have mental health problems, 10 percent have severe mental health issues, and roughly a quarter have IQs under 70. She said most prison mental health departments in Louisiana have at least three full-time social workers. Angola has at least 11. Here, there are few options for inmates with mental health needs. They can meet with Miss Carter, but with her caseload of 450 prisoners, that isn’t likely to happen more than once a month. They can try to get an appointment with the part-time psychiatrist or the part-time psychologist, who are spread even thinner. Another option is to ask for suicide watch.

A CO sits across from the two official suicide watch cells, which are small and dimly lit and have plexiglass over the front. My job is to sit across from two regular segregation cells being used for suicide watch overflow, observe the two inmates inside, and log their behavior every 15 minutes. “We never document anything around here on the money,” Miss Carter taught us a month ago. “Nothing should be 9:00, 9:15, 9:30, because the auditors say you’re pencil-whipping it. And truth be known, we do pencil-whip it. We can’t add by 15 because that really puts you in a bind. Add by 14. That looks pretty come audit time.” One guard told me he just filled in the suicide watch log every couple of hours and didn’t bother to watch the prisoners. (CCA’s spokesman says the company is “committed to the accuracy of our record keeping.”)

For one inmate, Skeen, I jot down the codes for “sitting” and “quiet.” For the other, Damien Coestly (his real name), the number for “using toilet.” He is sitting on the commode, underneath his suicide blanket, a tear-proof garment that doubles as a smock. “Ah hell nah, you can’t sit here, man!” he shouts at me. Other than the blanket, he is naked, his bare feet on the concrete. There is nothing else allowed in his cell other than some toilet paper. No books. Nothing to occupy his mind.