Two-year-olds at a preschool in St. Petersburg, FloridaScott Keeler/Tampa Bay Times via ZUMA

The Obama administration released a new list of regulations today meant to improve the quality of child care in thousands of centers—from small mom-and-pop shops to large nonprofit and for-profit schools—serving infants and toddlers. Currently, every state has its own safety, health, and learning standards for child care centers, whose quality varies widely. The new federal standards aim to raise the bar for every center that works with any of the 1.4 million low-income children currently receiving a federal subsidy to cover their child care fees.

The new rules require, among other things:

- More thorough background checks for all staff working in child care centers;

- Unannounced inspection visits of child care centers that will be posted publicly for parents;

- Regular mandatory training for child care providers, including safe sleeping practices, preventing infectious diseases and administer CPR, and spotting and reporting child abuse;

- More professional development of educators.

“In some states, it is easier to become a child care provider than a hairdresser or a dog walker,” Brigid Shulte, the director of New America’s Better Life Lab, told Mother Jones. The new standards are a very important first step, Shulte added, but the rules cover only a small percentage of the roughly 12 million kids younger than five in the United States.

Shulte is the co-author of the just-released “The Care Report,” which analyzed the quality, cost, and availability of child care in 50 states. Using data from Care.com, New America, and many other recent studies, researchers found:

Child care is very expensive in the United States. The average full-time cost of child care centers for children ages zero to four is $9,589 a year, higher than the average cost of in-state college tuition ($9,410). Infant care is particularly expensive: Full-time care for babies in centers ranges from a low of $6,590 in Arkansas to a high of $16,682 in Massachusetts. In 33 states, one year of infant care in a center is more expensive than a year in public college. And while early care is subsidized in virtually every other advanced country, 60 percent of US child care costs are paid by parents, 39 percent by the government, and only 1 percent by businesses and philanthropy. Another study found that in Sweden, parents spend about 4 percent of their net income on child care; in France, Germany, and Denmark, about 10 percent. “It’s not surprising that our fertility is lowest in history,” Shulte said. “We make it very difficult for parents to have kids.”

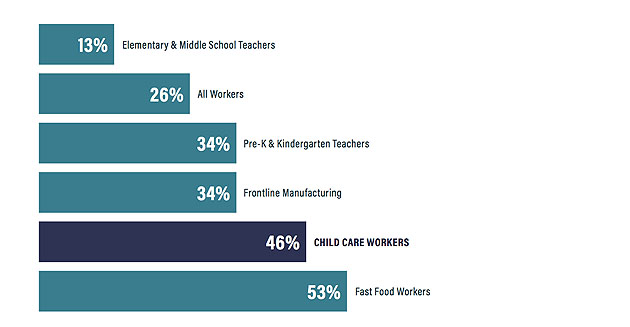

Early-learning teachers make poverty wages, which contributes to high turnover and poor quality of care. The median wage of a teacher in this field is $9.77—less than what most janitors and parking garage attendants make. It’s no surprise then that nearly half of the 2 million preschool and child care teachers are enrolled in some kind of public support program, receiving food stamps or welfare assistance.

The quality of child care is low and is the worst for ages zero to three—the most crucial stage for brain development. Only 11 percent of child care centers are accredited by the National Association for the Education of Young Children or the National Association for Family Child Care. The rest operate under state standards and licenses that all have varying—and mostly mediocre—rules and regulations.

Very few poor kids receive help. Only 1 in 5 low-income kids receive federal subsidies to cover child care costs.

Many policymakers still think that taking care of infants and toddlers is “babysitting,” Shulte said. But the research shows otherwise: The first three years of a child’s life are the most important for brain development, and parents or caregivers require specialized knowledge and training to promote important cognitive, social, and emotional skills.

That sort of training costs money, of course, but researchers like Nobel-winning economist James Heckman and others have argued that investments in these early years yield the greatest returns to society. Steven Barnett, a professor of economics and the executive director of the National Institute for Early Childhood Research, calculated that every $1 the government invests in high-quality early education can save more than $7 later on by boosting graduation rates, reducing crime, and increasing tax revenue.

Funding and enrollment for preschool is regaining its momentum since the recession: In 2012, 66 percent of American four-year-olds went to preschool. But despite these gains, the United States still ranks 30th (out of 44) for preschool enrollment among developed nations. And when it comes to child care from birth to age three, the US spends little to nothing: Only 6 percent of total spending goes to this age group, according to Paul Tough, the author of Helping Children Succeed. Compared to other nations, the United States ranks 31st out of 32 developed nations when it comes to government spending on early childhood education.

Getting the United States all the way to high-quality early learning is a long road, the authors of “The Care Report” argue, one that must start with sufficient and sustained funding from the public and private sectors. Other proposed solutions in the report include universal paid family leave, expanding cash assistance programs, and universal pre-K, and providing better training and pay for teachers. “Research tells us that the vast majority of achievement gap you see in high school opens up before kindergarten,” Shulte said. “The work to transform early learning is urgent if we want to reduce these gaps—like other countries with better early childhood policies have done.”