Students in a fourth-grade classroom in Waukegan, Illinois.Jose M. Osorio/Chicago Tribune/TNS via ZUMA Wire

As Immigration and Customs Enforcement officers ramp up arrests and deportations of undocumented immigrants, teachers and school staff across the country say they’re seeing a deeply negative impact on many of their students who worry they’ll go home to find loved ones missing. According to a working paper released Wednesday by researchers at the UCLA Civil Rights Project, staffers working in elementary and secondary schools report that they’re observing emotional and behavioral problems, as well as missed classes and increased fears and anxieties among immigrant students, defined as those with immigrants in their families.

The study, which received more than 5,400 responses from administrators, teachers, and staff at more than 730 schools in 12 states, found that two-thirds of respondents noticed ramifications from immigration enforcement in their schools. One in four administrators said it was a “very big” problem.

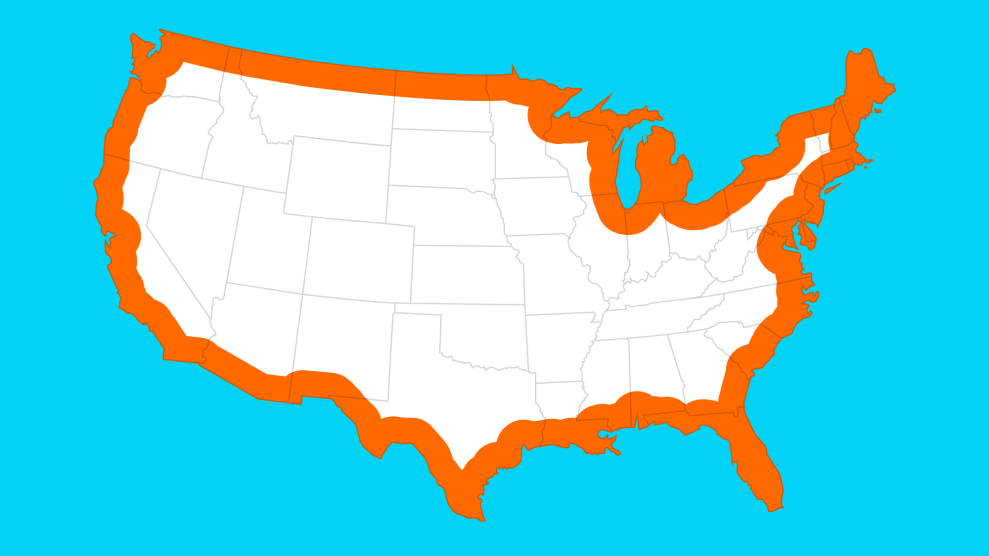

More specifically, almost 90 percent of administrators and nearly 80 percent of teachers said they had observed behavioral or emotional problems in immigrant students, such as crying and acting anxious or depressed. Schools that responded in the South—those in Arizona, Florida, Georgia, and Texas—were more likely to see problems than in other regions; these respondents in the South were also significantly more likely to report absenteeism, with two-thirds saying it had become a problem. Similarly, two-thirds of respondents in the region saw students’ academic performance decline due to immigration concerns; teachers said some students’ grades had plummeted, while others appeared distracted in class.

The report also found that two-third of educators noticed that concerns about immigration were having an indirect effect even on non-immigrant students, meaning they showed anxiety and concern about immigration or that they expressed worry about their friends’ immigration statuses, among other behaviors. In the South, 70 percent of educators reported this effect.

Patricia Gándara, a professor at UCLA and one of the co-authors of the study, says she worries that legislative efforts around Deferred Action for Childhood Arrivals, or DACA, ignores the effects deportations are continuing to have on families. “No one is talking about the parents of these people or the parents of our kids in K-12 schools, the huge majority [of whom] are US citizens,” she says. “Until immigration enforcement is changed for these people it will continue to affect the schools negatively.”

The study is the first to explore the effects of immigration enforcement within classrooms across the country. The authors sent surveys to 47 school districts across 12 states. California institutions made up nearly 45 percent of the responses, likely in part due to the state’s high number of undocumented immigrants. More than 80 percent of schools that responded to the survey were Title 1, or low-income schools.

Gándara tells Mother Jones that she was struck by how moving and upsetting the responses were. A teacher in Maryland wrote that one student attempted to slit her wrists because her mother had been deported. One art teacher in Texas observed students drawing “colored images of their parents and themselves being separated, or about people stalking/hunting their family.”

The study’s authors conclude that schools will continue to “bear the brunt” of immigration enforcement policies, especially Title 1 schools that are already facing other challenges. “We are making it near impossible for [these schools] to improve educational outcomes when we put such enormous pressure on them,” says Gándara. “We have to ask ourselves: Is this who we are as Americans? Terrorizing children and stressing out their teachers? I assume that these are unintended consequences—probably no one thought about the impact this would have on the nation’s schools, but educators are telling us that it’s huge.”