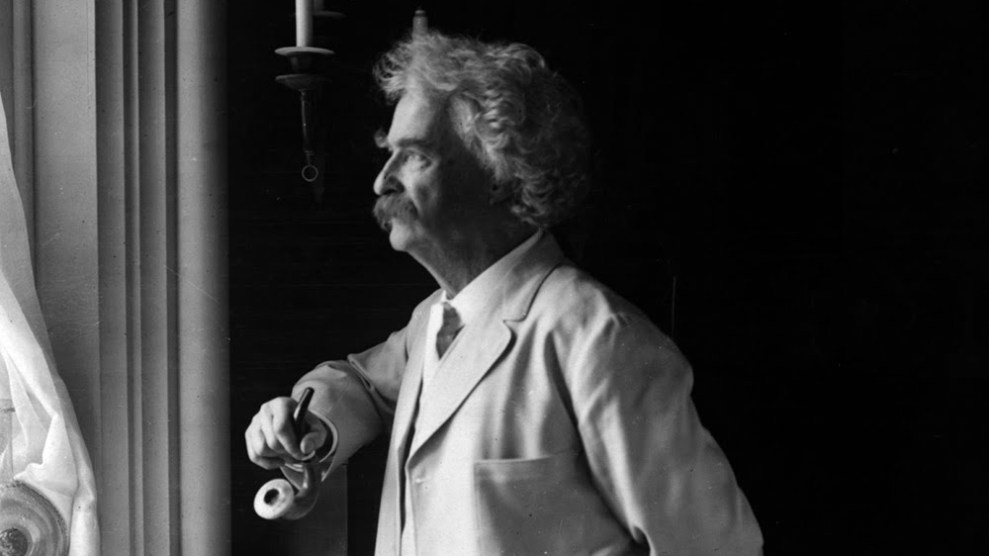

Mark TwainWikimedia Commons

The nomination of Gina Haspel to be President Donald Trump’s CIA director has become something of a referendum on torture. Not so much on the use of torture in the here-and-now. Even though Trump in 2016 called for re-deploying torture against terrorist suspects, Haspel, a longtime CIA official who was involved in the agency’s use of waterboarding in the post-9/11 period, stated during her confirmation hearings that now she does not support resorting to torture and that she accepts “the higher moral standard.” But when testifying, Haspel refused to concede that the Bush-Cheney embrace of waterboarding and other forms of torture had been immoral. In essence, she would not acknowledge the CIA had taken a terrible turn.

That is what’s at the heart of her confirmation process. Despite Trump’s rhetoric, the question is not the revival of torture but the admission that the United States had been wrong to employ it, even during the collective freakout following the horrific 9/11 attacks. Haspel ran a CIA facility in Thailand where waterboarding had occurred, and she played a role in the now controversial destruction of videotapes of waterboarding sessions. (The tapes were destroyed, though CIA lawyers and White House officials had not approved.) The Senate vote on her nomination is scheduled for Wednesday. And throughout her confirmation, she has walked the fine line between rejecting future torture and justifying its past use.

In one regard, Haspel’s nomination could have been met with a sigh of relief. Trump had not picked a political hack for this position. Haspel is a career intelligence professional. That carries both pluses and minuses. Agencies often require leaders with outside perspectives, and an insider might be overly protective of her longtime employer. Yet in the Trump administration, expertise is devalued and scorned. The capacity and knowledge contained within federal departments is frequently dismissed or held suspect. So the prospect of an intelligence service being run by someone who knows intelligence work could be refreshing. How novel.

Still, Haspel’s baggage is weighty. Rewarding her with the top CIA spot would send a signal that it’s okay to accept extremism in desperate times.

Which brings me to Mark Twain.

The debate over torture is not new for Americans. In the late 1890s, the United States, a bit heady after its defeat of Spain in the Spanish-American War, seized the Philippines as a spoil of war. This came at a time when the nation was immersed in a bitter debate over whether the United States, a nation founded on the premise of self-determination, should pursue imperial ambitions and subjugate others overseas. Teddy Roosevelt, then governor of New York, led the charge for empire (in overtly racist terms), and President William McKinley heeded the call and claimed the Philippines.

This foundational debate is chronicled masterfully by Stephen Kinzer in his recent book, The True Flag: Theodore Roosevelt, Mark Twain, and the Birth of the American Empire. As Kinzer notes, the American takeover of the Philippines led to the United States waging a bloody and cruel counterinsurgency campaign against Filipino rebels who, after being liberated from Spanish colonialism, preferred to be free rather than be ruled by Washington. In their efforts to quash the rebellion, US soldiers turned to a form of torture that the Spaniards had brought to the Philippines: the “water cure.” This method had been developed during the Spanish Inquisition to punish heretics. A victim would be restrained and water forced down his throat—and then the perpetrators would stomp on the victim’s stomach, until a confession or death occurred. (Waterboarding, by contrast, simulates drowning but does not actually entail forcing water into the person.)

When word of the “water cure” reached the United States, it triggered protests. Imperialism, some critics argued, was turning Americans into monsters. As Kinzer writes, Twain, then living in London, was among the critics. Kinzer quotes Twain’s outrage over this practice: “To make them confess—what? Truth? Or lies? How can one know which it is they are telling? For under unendurable pain a man confesses anything that is required of him, true or false, and his evidence is worthless.” News of the excesses and violence of the war in the Philippines appears to have bolstered Twain’s anti-colonialism. Upon his return to the United States in 1900, he declared himself an anti-imperialist. “A year ago, I wasn’t,” he said. “I thought it would be a great thing to give a whole lot of freedom to the Filipinos. But I guess now that it’s better to let them give it to themselves.”

A subsequent Senate inquiry into the war in the Philippines, which ended in 1902, essentially covered up the use of the “water cure” and other US military abuses. An editorial writer for the New York World, according to Kinzer, put it this way: “The American public sips its coffee and reads of its soldiers administering the ‘water cure’ to rebels…and remarks, ‘How very unpleasant!’ It then butters its bread.”

The main point here is not to predict what Twain would say about the pending vote on Haspel, but to observe that the United States has previously confronted this matter: how to face up to its use of torture in the pursuit of national security aims. Indeed, the Senate intelligence committee in 2014 did release a lengthy and critical report on the Bush-Cheney administration’s use of torture. But Haspel’s nomination and likely confirmation suggest the nation has not changed all that much in the past century when it comes to contending—or not contending—with its darker side.