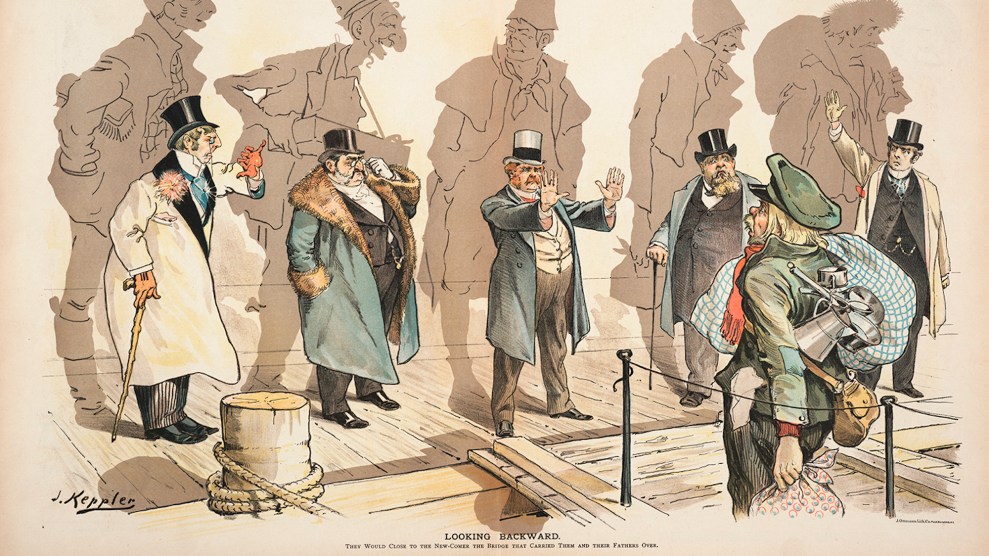

An 1893 cartoon titled "Looking Backward" depicts the irony of American immigrants turning away additional newcomers. The caption reads: "They would close to the new-comer the bridge that carried them and their fathers over."Billy Ireland Cartoon Library & Museum at the Ohio State University

Boston’s 1845 census grouped the home countries of the city’s indigent into three buckets: the United States, Ireland, and everywhere else. Massachusetts Protestants Irish immigrants for draining public resources. The state’s solution was to deport people it considered likely to become “public charges.” That same strategy is now at the center of the Trump administration’s attempt to reshape legal immigration in the United States.

US Citizenship and Immigration Services, the agency that handles legal immigration, is on the verge of releasing a regulation that is expected to make it far easier to label immigrants as likely future public charges. That would prevent immigrants in the United States from extending their time in the country or receiving green cards and a path to citizenship.

In deciding whether someone is likely to become a public charge, USCIS currently considers only whether that person receives cash benefits, like welfare. The new rule would allow the agency to deem people public charges if they or their US-born children receive non-cash benefits like food stamps or heating assistance.

The Migration Policy Institute, a nonpartisan Washington think tank, concluded last month it would be “unprecedented” to enact such a major overhaul of future legal immigration without congressional input. The White House Office of Management and Budget announced in December that USCIS is working on the rule and that it could be released and submitted for public comment at any time. It is expected to be released before the midterm elections to motivate President Donald Trump’s anti-immigration base.

Blocking the poor from entering the country is nearly as old as US immigration law itself. In his 2017 book, Expelling the Poor, Hidetaka Hirota, an assistant professor at Waseda University in Tokyo who previously taught US immigration history at the City College of New York, explains how Massachusetts and New York created the foundation for US immigration restrictions by turning away and deporting Irish migrants fleeing the potato famine in the 1840s. When the United States adopted its first comprehensive immigration law in 1882, both states made sure there was a public charge provision that allowed immigration officials to exclude impoverished Irish migrants. The current version of that provision states that immigrants who are “likely at any time to become a public charge” will not be admitted into the United States or allowed to adjust their immigration statuses. Now, the Trump administration hopes to use this provision to target migrants who are disproportionately people of color.

In March, the Washington Post published a full draft of a public charge rule that would make substantial changes to the government’s execution of the provision. In 1999, the Clinton administration issued guidelines stating that only cash benefits like welfare would be relevant in determining whether an immigrant was likely to become a public charge. The new draft rule would require USCIS to count a long list of additional government assistance programs as “public benefits” that can cause someone to be labeled a public charge and made ineligible for a visa or green card. Those include nutrition assistance for infants born in the United States, subsidized Obamacare, and earned income tax credits. (Certain benefits, including public education and unemployment benefits, would not be considered in public charge determinations. Asylum seekers and refugees would also remain exempt from public charge rules.)

Undocumented immigrants are already blocked from receiving almost all public benefits. Although recent legal immigrants face similar restrictions, they could still be deemed public charges because of the benefits their US-born children receive. The Migration Policy Institute estimated in June that the share of noncitizens who could be considered public charges would jump from 3 percent to 47 percent under the draft rule. Additionally, the group noted, many immigrant families who are not directly impacted by the rule could stop using public benefits out of fear of the perceived consequences.

The Department of Homeland Security’s current standard requires someone to be “primarily dependent” on the government before he or she is considered a public charge. The draft rule states that DHS arrived at a new and much more expansive definition of what a public charge is after looking up the phrase in “various dictionaries,” including Dictionary.com. Those definitions, the draft rule states, “generally suggest” that anyone receiving public benefits is a public charge. The draft proposes setting the public charge threshold for a family of four at about $753 in public benefits per year, or about 50 cents per family member per day.

David Bier, an immigration policy analyst at the libertarian Cato Institute, wrote in April, “Nothing in the legislative history or judicial record endorses such a broad rule.” In its treatment of public charges, he argued, the 1891 law that centralized federal authority over immigration was referring to extremely impoverished people, not immigrants who mostly pay their own way but receive minor government benefits. In 1917, a federal appeals court held that Congress had intended for the public charge clause to keep out the poorest of the poor—”persons who were likely to become occupants of almshouses.”

At a talk hosted last month by the Center for Immigration Studies, a group that calls for dramatic cuts to legal immigration, USCIS Director Lee Francis Cissna described the forthcoming rule as a “very rational and reasonable” effort to interpret the law. His goal, he said, is “simply to enforce” a measure that’s been on the books for more than 100 years.

Cissna didn’t address how that provision got on the books. Immigration control before 1882 was largely left to the states and was based on British poor laws from the 17th century. Those laws allowed paupers to be returned to the area responsible for them, which were often nearby towns or states. Excluding and removing foreigners became much more common in the United States as Irish migration picked up in the 1830s and exploded during the potato famine.

Protestant nativists portrayed the Irish as culturally inferior Catholics who drove down wages by undercutting American workers. Overseas landlords amplified those fears by paying for many destitute Irish tenants to get to America. Thomas Whitney, a New York congressman at the time, argued that European landlords were sending America “a disease, both moral and physical—a leprosy—a contamination.” Between 1849 and 1854, more than 60 percent of all people admitted to the New York City Almshouse were born in Ireland, according to Expelling the Poor. The vast majority of Irish immigrants paid for their own journeys, but it was the image of the Irish immigrant offloaded from abroad that stuck.

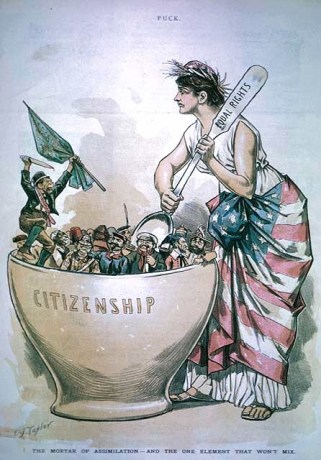

An 1889 cartoon titled “The Mortar of Assimilation—And the One Element that Won’t Mix” shows an Irishman holding a knife and a green flag.

Wikimedia Commons

In 1837, Massachusetts allowed port officials to block people from disembarking if they had been paupers in their home country or were a “lunatic” or “idiot.” Ship captains could get around that by putting up a $1,000 bond to cover the potential costs of caring for their passengers in the United States. In a similar vein, the USCIS draft rule would allow some immigrants to overcome a public charge determination by posting a bond of $10,000 or more and agreeing not to use any public benefits until they become citizens. The amount of the bond would not be subject to appeal, and the bond would be returned only after an immigrant becomes a US citizen, leaves the country, or dies.

An 1847 New York law blocked people “likely to become permanently a public charge” from entering the United States without a bond, and Massachusetts enacted similar legislation the next year. But it was never clear what “likely” meant, and state officials had almost complete discretion over whom they let in. “When this legal power was combined with officials’ own nativist sentiments,” Hirota writes, “the implementation of immigration policy became exceedingly coercive.” New York had a policy only for excluding immigrants, but Massachusetts allowed for deportation as well, often using that authority to send people to New York, even if they had no obvious ties to the state.

After the Supreme Court curtailed state-level immigration laws in the 1870s, East Coast states campaigned to pass national legislation to exclude the poor and other undesirable immigrants. (Much like today, their efforts were opposed by chambers of commerce that favored more open borders.) Nativists in California helped secure a 10-year federal ban on Chinese immigrants in May 1882. Three months later, Congress passed the 1882 law that blocked any immigrants unable to take care of themselves “without becoming a public charge.”

As with the state laws, it was never clear where to draw the line. In 1887, after immigration officials detained 71 Irish immigrants because their travel was paid for by the British government, a New York district court judge ruled that it was irrelevant who had paid for the trip and released the immigrants from detention. An Irish woman who was allowed to join her husband in Massachusetts rejoiced, saying, “God be praised,” according to the New York Times. “We are spared.” The Times lamented in an opinion piece that the decision meant “we must receive and support the human dregs of the Old World,” and the paper warned that along with the Irish, “monthly consignments of Neapolitan mendicants,” Russians, and Slavs would soon arrive in a “dirty flood.” That was particularly concerning, the paper said, because the country was no longer “sparsely settled” and “greatly in need of unskilled labor.” (There were about 60 million people in the United States at the time.)

Hirota told me that technically, the public charge provision has always applied to everyone. “But then when it comes to the implementation,” he continued, “the target is always clear.” Originally it was the Irish, and now it’s Hispanic immigrants, he said. The draft rule would also make it easier to exclude immigrants who make less than 250 percent of the federal poverty line, or about $62,000 for a family of four. The Migration Policy Institute found last month that 29 percent of recent legal immigrants from Mexico and Central America would clear that bar, compared to 77 percent of those from the United Kingdom. (Ian M. Smith, a DHS immigration policy analyst who left the agency last month due to his ties to white nationalists and long record of anti-immigrant writings, worked on the rule, according to the Washington Post.)

While there are many historical parallels, Hirota points to a key difference. Originally, the United States sought to exclude immigrants who would become completely dependent on the government. Now, the Trump administration hopes to target working immigrants whose families receive only some assistance. A family of four making 200 percent of the poverty line may struggle to make ends meet, but it wouldn’t be a family of paupers, either. “It’s part of the government’s crusade against immigration regardless of the legal status,” Hirota said. “Put simply, it’s a purely nativist agenda.”

At the Center for Immigration Studies event, Cissna dismissed these concerns and tried to downplay the importance of expanding the public charge rule. “There’s nothing malevolent or diabolical in it,” he said. “It is a sincere, good-faith attempt to interpret what that provision means.”

Image credit: Billy Ireland Cartoon Library & Museum at the Ohio State University