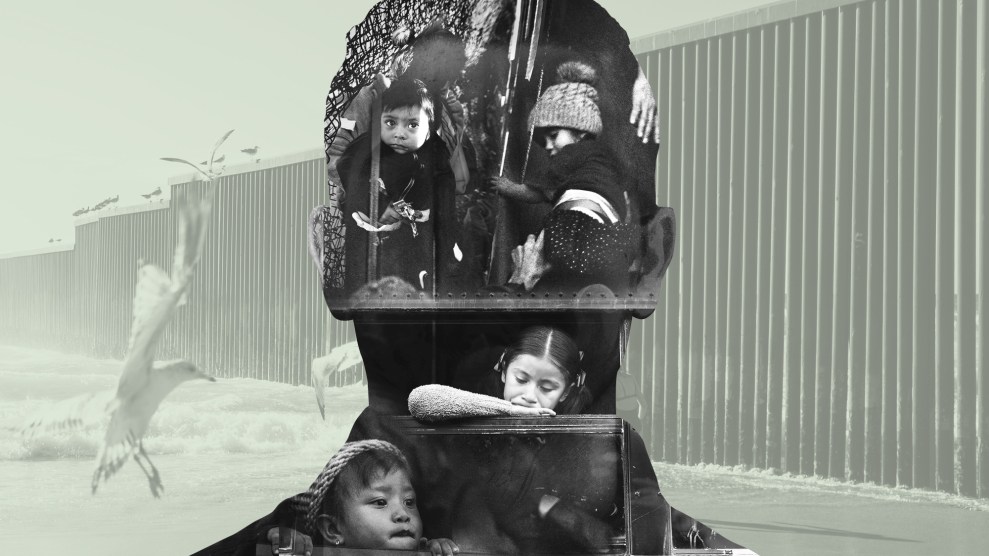

Mother Jones illustration; ZUMA; Getty

Carlos doesn’t like to talk much about growing up in Honduras. The first time we met, at an office near downtown Los Angeles, he’d look down at the table and give me one-word answers every time I brought up his childhood. It wasn’t until our third meeting that he opened up a bit more: When he was four years old, he told me, his father was killed in Tegucigalpa. Soon after, his mother left him by a dumpster and walked away, abandoning him to a life on the streets. “I haven’t had any family since I was a little kid,” he said, “so I’ve gone through life on my own.”

By the time Carlos was 6, he already had his first job, cleaning vegetables for a sidewalk vendor. He made the equivalent of $2 a day, and he’d save it to pay for school. Carlos did that until he was 9, when he ended up in the hands of the local child welfare agency. Officials moved him into a government shelter, where he said he saw staff beat up the kids and even burn their hands when they misbehaved. That’s when he ran away for the first time.

Carlos was homeless for most of his life in a city where a teenage boy is expected to work with the gangs or be killed. He lived under a bridge for a while, but last fall, not long after he moved into a small shack, “something happened.” Shortly after, gangs shot up his shelter. “You’re supposed to just put up with it there,” he said.

Last October, Carlos decided to flee the country with hopes of seeking asylum in the United States. A large migrant caravan was forming, so he rushed to meet up with the thousands of migrants already in Guatemala to avoid making the trek north alone.

But unlike thousands of unaccompanied minors from Central America migrating recently, Carlos didn’t have anyone in Honduras looking out for him, and he didn’t have anyone in the United States waiting for him, either. He was 17, and he was truly alone.

In recent weeks, the reporting from the border has been especially grim. Rep. Alexandria Ocasio- Cortez (D-N.Y.) toured overcrowded immigration detention facilities in El Paso and called them “concentration camps,” saying their conditions were inhumane and intentionally cruel. A report released by an oversight agency under the Department of Homeland Security showed photos of women and children crammed in small holding cells without warm meals or access to showers. Over the weekend, the New York Times and the El Paso Times copublished an investigation into harrowing conditions at a Border Patrol station in Clint, Texas, where hundreds of asylum seekers—many of them unaccompanied minors like Carlos—were going to bed hungry and forced to sleep on the floor.

But when Carlos, who requested we not use his last name for privacy and safety concerns, fled Honduras some nine months ago, he was focused solely on the treacherous journey in front of him: making his way through Central America and Mexico to the US border.

Once he headed north, he became part of a larger trend that has flummoxed American immigration officials in two administrations over the past five years—one that shows no signs of abating anytime soon. From October to June, the first nine months of the current fiscal year, US Customs and Border Protection encountered some 63,600 unaccompanied children and teens along the border with Mexico. That’s a 70 percent increase from the same period last fiscal year and the highest annual number yet for the agency. As has been the case since the numbers started to spike in late 2013, the vast majority of these kids are coming from Guatemala, Honduras, and El Salvador. Since my colleague Ian Gordon wrote about the surge of unaccompanied minors in 2014, when more than 68,000 kids showed up at the border on their own, CBP has encountered more than 323,000 unaccompanied minors.

In the past, when underage migrants presented themselves at the border, US immigration officials would typically take them in and process their cases. They would then end up in US custody, first in temporary facilities operated by the Border Patrol (like the Clint patrol station), then in long-term shelters run by the US Department of Health and Human Services. Eventually, HHS would connect the kids with distant relatives or with sponsors.

But in recent months, the Trump administration has put an extra hurdle in front of underage migrants. Since last fall, US officials have been turning away underage asylum seekers, often sending them back to Mexican authorities or to the dangerous streets of Mexican border towns. The Trump administration has denied it, but this practice has been reported consistently across the border. Jenny Villegas, a migrant justice organizer with the Central American Resource Center (CARECEN) in Los Angeles, has seen it firsthand. “We started to see the way that the kids were particularly vulnerable,” she said. “We knew that Tijuana was not a safe place for them.”

When more than 5,000 Central American migrants arrived in Tijuana as part of the caravan last fall, the Mexican government set up a shelter in an old sports complex where thousands slept under crowded tents. Hundreds of kids and teens heading for the United States found themselves there, too—including Carlos.

Villegas started visiting the tents regularly to meet with unaccompanied minors. She’d talk to them about the possibility of moving to a different shelter that specifically housed migrant kids, and during one of those visits she met Carlos.

“I talked to him about the youth migrant shelter, but he wasn’t very interested in hearing what I had to say,” Villegas said. A lot of that, she suspected, was distrust: Many migrants are scammed, robbed, kidnapped, or trafficked on their journeys north, “so whenever a kid was distrustful, I would tell them that’s smart—don’t trust me until I prove that I’m a trustworthy person.”

Villegas went to the tents every day, and Carlos eventually started chatting with her. Still, he remained distant, and he declined to go to the youth shelter that Villegas recommended. She left for Los Angeles hoping he would find his way there on his own.

Carlos bounced around from the tents to another adult shelter to the Mexican child welfare agency and eventually to the streets again. He’d seen things no one, let alone a teen with no support system, should have to see. “You see people dying, falling behind and dying, and at the end of the day, the trauma from that and from all the things that happened to me are things I’m still struggling with,” he said.

After two months in Tijuana, Carlos finally made it to the youth shelter, Casa YMCA. When he arrived, he met other Central American teenage boys and girls also waiting to ask for asylum or meet up with relatives in the United States. Better still, he had a place to sleep, warm meals, and the security he didn’t have while on the streets or at shelters for adults. He spent Christmas there and became close with many of the other teens. But it wasn’t easy to get used to the rules or the overcrowding at the shelter—the 25-bed facility was housing 60 teenagers after the caravans.

Carlos spent about a month and a half at Casa YMCA, where he eventually reconnected with Villegas. He told her that he felt motivated and more optimistic about his future, and he shared his goal of going to school in the United States to become an immigration lawyer.

The more Carlos talked with the other teens, the more he learned about the system. That’s when he got the idea to start a Facebook group for the teens to stay in touch with each other once they left the shelter. “Carlos is kind of a leader, so he very much took a leadership role within the house,” Villegas said. “He was sort of like an advocate for a lot of the kids.”

The private Facebook group has about 26 members now, most of them friends from Carlos’ time at Casa YMCA. The page’s cover photo shows 18 teens huddled together at the shelter; when Carlos showed me the photo on his phone, he smiled like I hadn’t seen him smile before. “Can you tell which one I am?” he asked me, and it took a second to scan the smiling faces of teenage boys and girls until I found him in the back, wearing a hat and trying to go unnoticed.

He scrolled through the posts quickly, reading excerpts from kids who had written about arriving with their relatives in the United States. They wrote grateful messages, some with selfies in their new homes. Kids video chatted constantly.

When Carlos first set up the Facebook group, most of the kids were living together at the youth shelter. In time, they started to go their separate ways. Soon, Carlos realized his window to enter the United States as a minor was starting to close: He was months shy of turning 18, and he was back in the streets of Tijuana after getting kicked out of the youth shelter for getting in a fight. So in March, a month shy of his 18th birthday, Carlos presented himself to US immigration officials.

John Moore/Getty Images

Once Carlos stepped foot in the San Ysidro Port of Entry near San Diego, he entered the custody of the US government. First, he was detained in a Border Patrol holding cell for four days—even though migrants, especially children, aren’t supposed to spend more than three days there. Then the government transferred him to the custody of the Office of Refugee Resettlement, the arm of HHS in charge of housing unaccompanied minors until they’re connected with relatives or sponsors in the United States. His phone was taken away, so he was unable to communicate with the Facebook group, and he was flown to the Homestead Job Corps Site in South Florida.

The Trump administration has asked for extra funding to be able to house about 23,000 underage migrants in ORR custody. The majority of kids in ORR shelters are 15-, 16-, and 17-year-olds, and if the numbers hold steady, this fiscal year HHS will care for the largest number of unaccompanied children in the program’s history. From October to May, the agency has released 46,312 children to sponsors across the United States; it reports that the average “length of care” in the last few months has been 60 days—up from around 45 days during the first child migrant surge in 2014.

When Carlos arrived at Homestead, it didn’t strike him as all that bad. “But I like being alone,” he said, “and they didn’t let you be alone.” There was too much security, he said, and that made Homestead feel like a prison. It scared some of the kids around him—they were having a much harder time than him, so much so that they talked about suicide—and he focused on comforting them.

As weeks passed, Carlos started to worry that he might not get out of Homestead before his 18th birthday. Once he was legally an adult, ICE could pick him up at the shelter and take him to an immigration detention center, where he could’ve remained for months or even years. Villegas and Jasmin Tobar, from the LA-based immigrant aid group SALEF, worked day and night to get him into a group home for unaccompanied minors in Los Angeles. “It took a lot of convincing that this was the best option for Carlos,” Villegas said, “because we knew that Carlos was going to need a lot of support and a lot of resources for his mental health.”

After 17 days, Carlos was released from government custody. He was put on a flight from Miami to Los Angeles, escorted by an ORR case worker, and finally given back his cellphone once he landed. He immediately posted on the Facebook page that he was all right, just as other teens had written posts when they connected with their families in the United States. That was the first of many posts he’d write from Los Angeles. Not all of them would be so positive.

When I met Carlos in April at the CARECEN office, he had been in Los Angeles for a few weeks and had already turned 18. He had been going to school and trying to pick up some English. Carlos was sort of cold at first, and our conversation was constantly interrupted by video calls and messages from other unaccompanied migrant teens in the Facebook group.

Before we met up, Villegas had warned me that Carlos had been having a hard time adjusting to this new life and that he was still haunted by his past in Honduras and his time in Mexico. “Think about the saddest story you’ve heard,” she said, “and that’s sort of been Carlos’s life.”

Once Carlos agreed to talk to me after a second visit, I noticed some scars on his forearms. He was wearing a sweatshirt with the sleeves pulled up to his elbows, and I could see what looked like more than a hundred cuts. The third time we met it had started to get warmer in Los Angeles, and he was wearing a short-sleeve shirt. His right arm showed fresh scabs.

When I asked him about it, he told me he cut himself when “the thoughts come up—that’s why I told you I don’t like to talk about that.” He ran his left index finger over his right forearm. “I feel a lot of pain inside, so I cut to let it out, to feel that pain on the outside.”

Villegas has encouraged Carlos to talk to a professional about it. “He actually lets me know that he’s going to do it,” she said. “Which is very difficult, because obviously I don’t want him to hurt himself.”

Carlos mentioned that he struggles with depression and that he tried to end his life by taking a bottle of pills while he was waiting in Tijuana. He described having flashbacks of traumatic situations and told me he didn’t want to talk about it anymore. “That’s why you have to keep the door closed,” he said. “Turn off the basement light and don’t turn it back on, because what’s there is ugly.”

At one point he pointed to his phone and said when he starts to feel down, he turns to his friends online. “When I feel discouraged,” he said, “I tell the group, and almost instantly I have like 56 messages from them motivating me, so I read them and I start to feel better.”

For months he’d been pouring his energy into helping other teens in the group connect with their families. He showed me a message he received from a boy whose brother was still in ORR custody. Carlos had been asked to contact the boy’s mother in Honduras on Facebook and ask her to take a picture of the boy’s birth certificate. Once Carlos got that photo through a Facebook message, he was able to send the birth certificate to the family member in the United States to get the boy out of the government shelter and into the home of his relatives.

With no relatives of his own in the United States, Carlos hopes to keep living at a long-term shelter in Los Angeles and continue going to school. Despite being 18 years old, he entered the United States alone as a minor and can apply for Special Immigrant Juvenile Status, which would allow him to remain in the country legally. He also has an asylum case pending after fleeing Honduras. There is no court date set for him yet, but Villegas said he is working with a lawyer in Los Angeles who will help him.

It could be months or even years before his immigration case is settled. But for now Carlos is getting used to life in the United States. It hasn’t been easy, but he feels safer here: “I can sleep now.”

This story has been updated to reflect new immigration data.

If you or someone you know is contemplating suicide, call the National Suicide Prevention Lifeline at 800-273-TALK (8255).

Image credit, from left: Megan Jelinger/ ZUMA, Lemmer Creative/Getty, Anadolu Agency/Getty, Carol Guzy/ZUMA, Carol Guzy/ZUMA, Carol Guzy/ZUMA