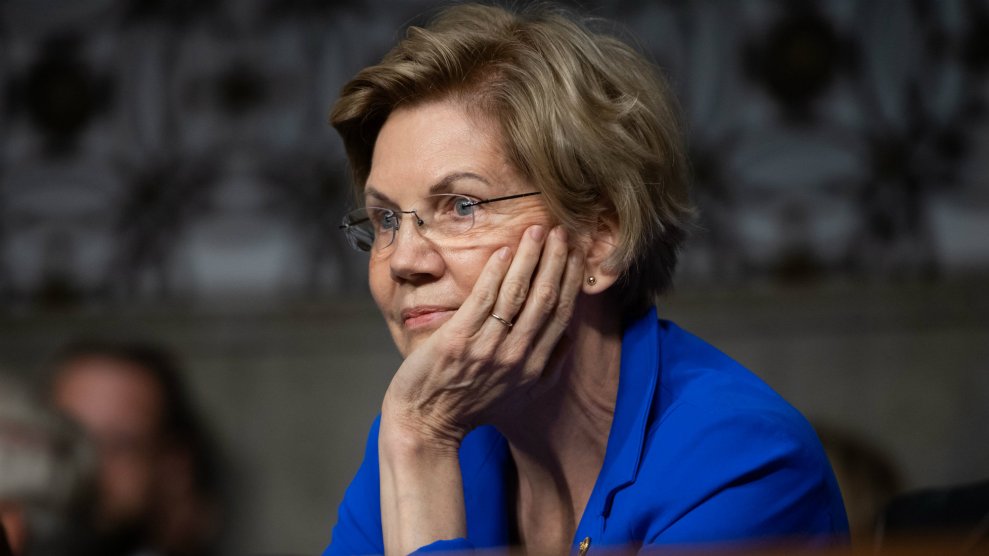

Sen. Elizabeth Warren (D-Mass.) was one of few lawmakers to challenge Defense Secretary Mark Esper's ties to Raytheon, a Massachusetts-based defense giant.Saul Loeb/AFP/Getty

The confirmation hearing for Secretary of Defense Mark Esper was a snoozer.

A few Senate Armed Services Committee members spent nearly three hours heaping praise on Esper, a decorated Gulf War veteran, for his decades of service in the military and as a staffer on Capitol Hill. The comity was interrupted only once, when one of the panel’s newest members, Sen. Elizabeth Warren (D-Mass.), chose to focus on a more recent line on Esper’s resume: specifically the seven years he spent lobbying for the defense giant Raytheon.

“This smacks of corruption, plain and simple,” she told him. “Will you commit that during your time as defense secretary that you will not seek any waiver that will allow you to participate in matters that affect Raytheon’s financial interest?”

Esper declined Warren’s request to make such a commitment and passionately defended his record. Committee chair James Inhofe (R-Okla.) apologized for what Esper “had to be confronted with” from Warren, describing the interaction as “unfair.” No one else had followed up on Warren’s efforts to have Esper stay out of Raytheon’s affairs entirely. Days later, 90 senators voted to confirm him.

Warren, a consumer protection icon who entered politics with a reputation as the bane of Wall Street, has spent the past several months treating defense contractors, generals, and civilian Defense Department officials to the same sort of withering criticism she grew famous for heaping on banking regulators and Wells Fargo CEOs. Her perch on the Armed Services committee has produced heated exchanges with Pentagon leaders over the department’s carbon footprint and its bloated war-fighting budget, but no topic has invigorated her more than the influence wielded by the $226 billion defense industry.

“It’s clear that the Pentagon is captured by the so-called ‘Big Five’ defense contractors—and taxpayers are picking up the bill,” Warren declared in November. “The defense industry will inevitably have a seat at the table, but they shouldn’t get to own the table.”

Defense giants and their allies in the Pentagon have long benefited from what Warren decried in May as “this business of more, more, more for the military.” Despite winding down its Middle East wars, the United States is still projected to spend $1.25 trillion on national security this year, according to the nonpartisan Project on Government Oversight (POGO), and Pentagon officials continue sounding the alarm for more funding to ward off China and Russia’s development of new cyberweapons and missiles. Warren, like many lawmakers from both parties, has frequently criticized corporate lobbyists for their swampy wheeling-and-dealing in Washington, but her “focus on DOD to this degree is new,” says Mandy Smithberger, director of POGO’s Center for Defense Information.

By tackling Pentagon spending and contractor malfeasance, Warren, one of the top-tier Democrats in the 2020 presidential primary, has been able to shore up her national security chops and tie the Defense Department to her attacks on corrupt government bureaucrats. This approach has also allowed her to be a different sort of Pentagon critic in the Democratic primary, unlike Sen. Bernie Sanders (I-Vt.) and Rep. Tulsi Gabbard (D-Hawaii), who have more directly assailed American military interventions. “It’s a ‘good government’ position, not a ‘left’ position,” says Gordon Adams, a former Pentagon official whose 1981 book, The Iron Triangle: the Politics of Defense Contracting, outlined the problem of close ties between government officials and industry leaders. “She’s saying the relationship is too cozy. And, she’s dead right.” Warren’s signature ethics plan would go “much broader than the current law,” says Craig Holman of Public Citizen, a consumer rights advocacy group. She proposes barring ex-national security officials from lobbying for foreign governments and urges prohibiting defense contractors from hiring senior DOD civilian and military leaders “for four years after they leave the Department.”

Despite criticizing the defense industry’s “stranglehold” on the Pentagon in November, Warren cannot completely disavow these companies, which have tremendous influence in her home state of Massachusetts. General Electric enjoys what the Boston Globe dubbed “near-deity status” in Lynn, where the company’s aviation plant has been based for more than a century, and both GE and Raytheon, the firm at the center of her exchange with Esper, are among Massachusetts’ top five employers. During her first Senate campaign in 2012, she tried to win their support and called William Swanson, then Raytheon’s chief executive, to chat about the “defense industry in Massachusetts” and the impact of federal budget caps on defense spending, the Globe reported at the time.

In February 2015 she received the type of headline from Politico her presidential campaign would likely cringe at now: “Warren takes care of defense business back home.” The article cited her support for several defense programs that employed Massachusetts residents but received less-than-stellar reviews from watchdogs like the Government Accountability Office. One program Warren supported, the Army communications network known as the WIN-T, had been slated for cuts until she and other Massachusetts lawmakers campaigned to rescue it. Four years later, Senate Armed Services Committee chair John McCain (R-Ariz.) deemed the program a “failure,” and even Gen. Mark Milley, then the Army’s top uniformed officer, admitted he had “serious, hard questions” about its efficacy. (The Warren campaign would not say whether she would still support this program now.)

Ted Kennedy, who occupied Warren’s seat in the Senate for more than four decades, also had to balance his broader industry criticism with support for economic engines in his home state, such as the GE plant in Lynn. “A lot of defense contractors would be criticized, but when it came to jet engines at Lynn—that he would vote for,” Adams says. (The full Massachusetts congressional delegation, including Warren, championed a $517 million contract for the plant in February.)

Warren’s campaign consulted POGO and People Over the Pentagon, a coalition of progressive groups that advocates deep cuts in defense spending, in the months following the campaign launch in February. Their influence is apparent in her Pentagon ethics plan, which Warren released shortly after the White House announced in May that Trump would nominate Patrick Shanahan, a former Boeing executive, as secretary of defense. (Trump never formally nominated him; Shanahan withdrew from consideration in June after reports emerged of violent turmoil within his family.)

Warren had her own history with Shanahan, who left Boeing in the summer of 2017 to serve as deputy to Trump’s first defense secretary, James Mattis. In March, she sparked an internal investigation into Shanahan for allegedly favoring Boeing during Pentagon meetings. He was ultimately cleared of any wrongdoing, but the central issue for Warren—an appearance of bias—remained relevant when Esper, the former Raytheon lobbyist, was later up for the same position. “My fundamental concern is that the relationship between the Defense Department and giant defense contractors has become far too cozy,” Warren said in a statement opposing Esper. Only five senators joined her in voting against him.