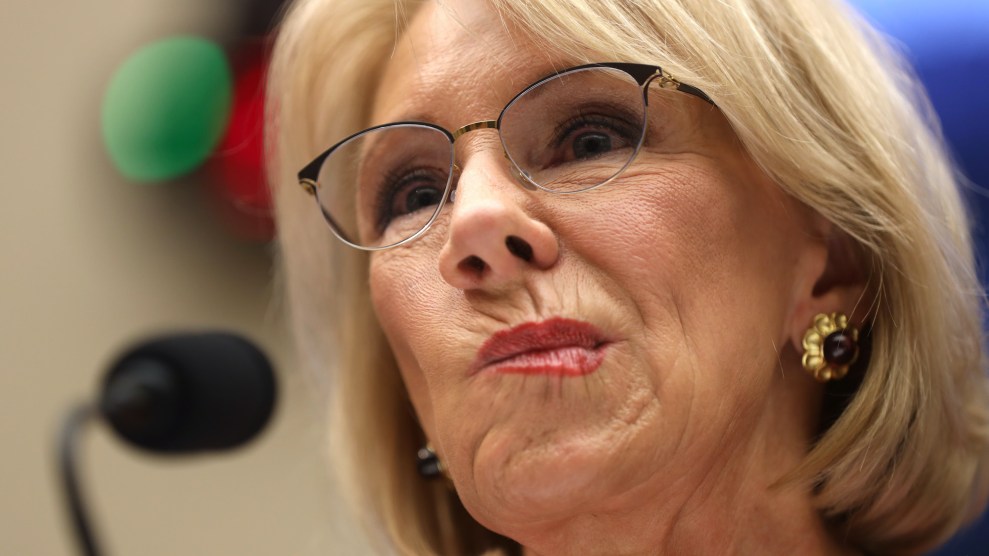

Alex Wong/Getty

Last week, when Education Secretary Betsy DeVos released new rules for how schools should handle reports of sexual assault and harassment, the American Civil Liberties Union issued a statement: “See you in court.”

On Thursday, it made good on its promise, filing a federal lawsuit against DeVos, the Education Department, and its assistant secretary for civil rights. The ACLU argues that Trump administration’s new campus sexual assault rules “dramatically reduce schools’ responsibility to respond to sexual harassment and assault” and “inflict significant harm” on survivors. The complaint is the first of several lawsuits expected to challenge a long-anticipated regulation that dramatically reinterprets Title IX, the federal civil rights law that prohibits sex discrimination in education.

The lawsuit was filed on behalf of four groups that advocate for student survivors of sexual assault and harassment, including Know Your IX, Girls For Gender Equity, Stop Sexual Assault in Schools, and the Council of Parent Attorneys and Advocates. Additional lawsuits from students, nonprofits, and state attorneys general are anticipated.

Since 2017, when DeVos rescinded the Obama administration’s guidelines on campus sexual assault, she has advocated ensuring “due process” for accused students and fairness in campus sexual misconduct cases, contrasting these changes with the previous administration’s emphasis on survivors’ rights. When the final Title IX regulation was released last week, she told reporters that it “recognizes we can continue to combat sexual misconduct without abandoning our core values of fairness, presumption of innocence, and due process.”

Both the Education Department and the ACLU predict that under the new rules, fewer reports of sexual misconduct will trigger investigations that could lead to an accused student being disciplined under Title IX. In its own justification for the regulation, the Education Department estimates that colleges on average will conduct one-third fewer sexual misconduct investigations under the new rules. “This is shutting students out of the reporting process before they even have a chance to have their report investigated,” says Ria Tabacco Mar, director of the ACLU’s Women’s Rights Project. She says the ACLU supports “fair process for complainants and respondents alike.” But, she adds, “creating barriers and making students jump through hoops to report sexual assault and harassment does nothing to ensure due process for all.”

The new rules require colleges’ disciplinary hearings to adopt many of the features of criminal trials, including live hearings and the cross-examination of the complainant and the accused by each party’s lawyer or representative. But in addition to overhauling the mechanics of campus disciplinary proceedings, the rules have also “radically reduced” colleges’ legal obligations to respond to sexual assault and harassment, the ACLU’s lawsuit argues.

The ACLU’s lawsuit focuses on the new rules’ “double standard” for harassment on the basis of sex. While schools must address harassment based on race, national origin, or disability if it is “severe, pervasive, or objectively offensive,” DeVos’s new rules define sexual harassment more stringently: If the alleged harassment is not “severe, pervasive, and objectively offensive” (emphasis added), the school must dismiss the complaint.

“It may seem like a small change, but it’s quite significant,” Tabacco Mar says. “You could have an instance of harassment that’s severe—something that we all acknowledge is reprehensible—but if it only happens once, then maybe it’s not considered ‘pervasive.’ On the other hand, you could have conduct that’s pervasive—something that’s happening to a student every single day—but because no particular incident is itself severe, schools are free to ignore the sum of the parts.”

There are other double standards in the new rules, according to the ACLU’s complaint. Unlike other types of harassment, sexual harassment is only required to be investigated if it is reported to a specific campus official such as a Title IX coordinator. “Under the prior standard, institutions could be on notice if students reported the conduct to trusted adults such as a campus security officer, professor, or athletic coach, if staff themselves witnessed the harassment, or if the incident was publicized in the media or flyers about the incident widely posted at the college,” the ACLU writes in its complaint. “No longer.”

All schools will be permitted to apply the “clear and convincing” standard of proof to determine whether a student is responsible for sexual misconduct. This is a higher standard than the “preponderance of the evidence” standard required by Obama-era guidance. (The “preponderance of the evidence” standard requires evaluating whether the misconduct was “more likely than not” to have occurred—the same standard of proof used by the Supreme Court in evaluating civil rights discrimination cases.)

The ACLU lawsuit notes out that while the new rules appear to allow schools to choose which standard of proof to apply, they also require schools to use the same standard for students and faculty. Because many colleges have collective bargaining agreements with faculty that require them to use the “clear and convincing” standard in faculty misconduct cases, those schools will effectively be forced to hold sexual harassment claims to a higher standard than other violations, Tabacco Mar says.

According to the ACLU complaint, the new rules also bar school administrators from conducting a formal Title IX investigation into most reports of sexual misconduct that occur off-campus, even if they affect the on-campus lives of students who, for instance, may have to share a class with their attacker. “Taken together,” the complaint says, provisions in DeVos’ regulations “radically undermine Title IX’s mandate that institutions prevent and respond to sexual harassment that interferes with students’ educational opportunities.”

Outside of court, survivor activists are planning ways to resist DeVos’ regulation, such as encouraging schools to voluntarily investigate complaints that the new rules would allow them to ignore. On Thursday, during a webinar hosted by the Institute for Research on Male Supremacism, Alexandra Brodsky, a staff attorney at Public Justice, reminded more than a hundred educators, researchers, students, and activists that the new regulations do not take effect until mid-August, giving them time to lobby school administrators who are deciding how to implement the new rules.

“This rule is not law yet,” Brodsky said. “A great tactic for getting your school to do the right thing is reminding them not to rush to comply with regulations that might be defeated in court.”

Read the full complaint here: