Mother Jones illustration; Getty

For the six months Carlos remained in the custody of Immigration and Customs Enforcement, he barely understood what was happening.

Carlos (whose real name we are withholding to protect his identity) fled his home country of Brazil in early November 2019 after having received death threats, watching gang members shoot and kill his 20-year-old son, and losing other relatives to the violence of organized crime. He boarded a flight to Mexico City with his sister and two nephews and traveled three days on a bus to Mexicali, a border town across from Calexico, California. On their way north, he said, Mexican police seized their food and money. He was left with nothing but a police report attesting to his son’s murder.

“I ran away because there was no solution,” he told me. “I was going to lose my life.”

But when they had reached their destination, Carlos permitted himself some hope. As they waved to border patrol agents, Carlos felt as though the security of a new life in the United States was almost as easy as crossing a street. But soon everything became confusing. The border patrol agents conducted a search and asked questions, but they were in English, and as a Portuguese speaker he couldn’t understand a word. Then he was separated from his family. Carlos was sent to the Imperial Regional Detention Facility in Calexico, a remote facility about 135 miles east of San Diego that houses up to 704 immigrants, most of whom are seeking political asylum. A California DOJ report documenting a June 2019 visit to the facility found that 80 percent of Imperial’s population was seeking political asylum. His sister and nephews were moved to another ICE detention center. From then on, Carlos was on his own.

Back in Brazil, the 47-year-old construction worker had completed only one year of school. He couldn’t read or write in Portuguese, except for his name. He also didn’t speak Spanish—which runs counter to the common assumption about migrants from non-Spanish speaking countries in South America. Carlos was among more than 10,000 Brazilians admitted to ICE detention in 2019—almost double the number from the year before. ICE’s Language Access Plan latest report shows that among the top 10 languages with the highest volume of requests for language services, Portuguese was the only one with a fulfillment rate lower than 90 percent. The agency also failed to meet a fulfillment rate higher than 50 percent for all but two of more than 20 indigenous languages.

Margaret Cargioli is the managing attorney at the Immigrant Defenders Law Center, a Los Angeles–based social justice law firm that handles approximately 600 new cases a year. “Individuals who have limited education or limited language abilities are vulnerable to not only due process violations,” she says, “but harm.”

Lacking the ability to communicate on the most basic level, Carlos had even less control over his immigration process, indeed over the circumstances of his daily life, than detained asylum seekers already have. The period Carlos spent in ICE detention was defined—and determined—by disorientation and isolation. He didn’t know he had to file an application for asylum to fight his deportation order, or that he would have to make his case before an immigration judge. He had no idea where his sister and nephews were, or how to get in touch with them. From accessing legal assistance and medical care to being able to respond to questions from guards or other detainees, migrants like Carlos are possibly the most marginalized of an already marginalized population.

Two weeks after his arrival in detention, Carlos had an initial asylum screening interview over the phone with the mediation of an interpreter. The asylum officer asked him if he had received documents explaining the purpose of that interview and a list of pro bono or low-cost attorneys and legal services organizations that could help him. “I don’t know how to read,” Carlos said, according to his credible fear interview records. When asked if he had been read his rights, he said he didn’t remember. “I know that I signed,” Carlos said, and went on to tell the asylum officer he couldn’t go back to Brazil or he would be killed. “Please help me,” he concluded.

Carlos would find distraction in playing checkers and watching television. Three times a day, officers conducted a head count and detainees were taken to the recreational area outdoors, even during the winter, when Carlos said he was so cold he couldn’t feel his fingertips. In a shared dorm with about 60 other detainees, he avoided fights by being the first or last to shower. With each passing day, he felt increasingly helpless.

And then, in March, four months after he had first entered Imperial, the coronavirus pandemic hit.

Imperial is operated by the Management & Training Corporation (MTC) under the first of three five-year contracts with ICE, which pays the company $143.14 per bed per day. Inside the privately run facility, dozens of migrants share cells with four bunk beds a few feet apart and have limited access to personal hygiene products. Grievances filed by a detainee at Imperial between April and July show the facility initially provided only 4-ounce shampoo bottles twice a week and only started offering hand soaps and sanitizers after repeated requests from detainees concerned about the pandemic. Immigrants also complained about officers conducting unannounced searches and fire drills and forcing groups of 25 or so unmasked detainees to wait inside a small recreational yard.

In a class action lawsuit filed in April, the ACLU of San Diego demanded the immediate release of immigrants from Imperial “due to the urgent threat to their lives and health posed by COVID-19.” The suit outlined how detainees reported that ICE continued to bring new people into the detention center without quarantining for at least two weeks. Lawyers were told that one detainee wasn’t removed from her dorm until after a weeklong fever, and another reported having symptoms only to be told by guards to take a packet of salt. The suit also underscores the added challenges non-English and non-Spanish speakers face at Imperial, where 30 to 40 percent of the population in June 2019 spoke Punjabi.

To follow announcements about COVID-19, asylum seekers had to rely on bilingual detainees to translate for them and were forced to “gather in close proximity around televisions in the common area.” They also often experienced even longer delays in receiving medical care. A recent review by California’s DOJ of immigration detention in the state found that Imperial and two other privately run facilities were “unsuccessful in meeting detainees’ language access needs. The report, published this month, noted that no one kept track of detainees’ primary languages or of those spoken by bilingual staff. “Failure to overcome these language barriers results in detainees being unaware of critical information; staff misunderstanding detainees’ concerns and positions; and staff having heightened difficulty managing emergency situations,” the report concludes.

Reports of poor conditions at Imperial aren’t new. During an inspection last year, the Department of Homeland Security’s Office of Inspector General identified several violations of ICE standards, including prolonged use of segregation without appropriate medical check-ins. The report found that some detainees were held in isolation for up to 23 hours a day and that 11 of the 16 detainees placed in administrative segregation for their protection, or that of other detainees and staff, or medical reasons, were isolated for more than 60 days, with potentially grave mental health effects. The OIG also observed that medical visits were conducted at times when asylum seekers were sleeping and concluded that “medical checks were insufficient to ensure proper detainee care, medical grievances and response were not properly documented, and ICE communication with detainees was limited.”

Before visitations were restricted as a result of the pandemic, Carlos was already mostly cut off from the outside world. Even the few points of access available to other detainees were inaccessible to him. He didn’t know how to use the available tablets to schedule calls and file grievances (although the OIG report also found that the tablets didn’t always work properly). He relied on other asylum seekers—some from India, others El Salvador—to navigate the day-to-day demands of detention. When Carlos, with the assistance of a fellow detainee, finally filled out his asylum application in April, it didn’t include a lawyer’s signature under the “declaration of person preparing form” field, but that of another asylum seeker.

Sometimes other migrants from Brazil were among the new arrivals, and Carlos enjoyed a brief respite from his isolation. But, he said, it didn’t take long before groups of three or four people from the same country ended up being separated without an explanation. For the most part, Carlos kept to himself.

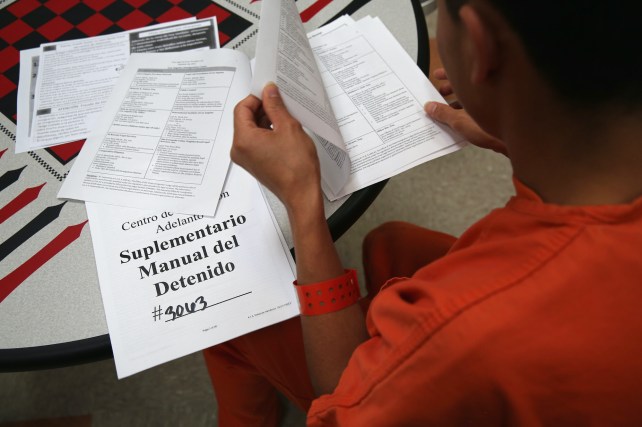

An immigrant detainee at the Adelanto Detention Facility in California.

John Moore/Getty

Other asylum seekers tried to help. They wrote letters to organizations working on their own cases asking if they could assist Carlos as well. At the time, Carlos said he didn’t even have money to buy paper, envelopes, or stamps. He received some responses from nonprofits, but most said they didn’t have the capacity to take on yet another case. In early March, a pro bono immigration attorney with the Catholic Charities of San Diego who worked on Carlos’ case briefly, filed a parole request with ICE on his behalf. It was denied.

Eventually, word of Carlos’ case reached a Brazilian translator at the fairly new organization Respond Crisis Translation, a global network of about 1,700 volunteers, often immigrants, speaking 88 different languages that partners with legal services providers and human rights groups to support migrants and refugees. “The US uses language to make access to asylum even more impossible,” the network’s founder, Ariel Koren, said, adding that COVID-19 has underscored the “language-based violence” that occurs in detention centers and often “gets lost” in the conversation. Since September 2019, the coalition has served almost 1,900 clients and translated nearly 15,000 pages worth of documents.

In April, Samara Zuza, the translator, connected Carlos with Cargioli and another attorney at Immigrant Defenders Law Center. Carlos had started working shifts at the detention kitchen seven days a week. The main upside: he got to eat more. He also earned $1.25 a day for eight-hour shifts that he then used to call the attorney with the Brazilian interpreter’s help. “I hadn’t spoken to anyone outside the detention until then,” Carlos said.

Zuza said that Carlos sounded scared and intimidated during their first conversation and had thought she was somehow affiliated with the government. “He was in complete shock” she said, “and just abandoned.”

His physical and mental health had dramatically deteriorated. After another detainee working in the kitchen tested positive for COVID-19, Carlos said he was placed in isolation in a windowless, 6-feet long and 3-feet wide cell. He presented no symptoms himself, but he started to have panic attacks and shortness of breath. Carlos said he tried to communicate with officers using gestures but was often ignored. “How were they supposed to understand me?” he asked. “They do it their way and there is no use in crying or begging.”

He estimates that he gained about 70 pounds while in detention. Without appropriate daily medication, Carlos said his chronic high blood pressure was through the roof, and sometimes he felt so dizzy he worried he was about to pass out. Soon, Carlos was showing symptoms of a possible heart attack. By the time the lawyers at Immigrant Defenders Law Center intervened, Carlos had reported having requested medical attention at least ten times over the previous months, without ever being provided a Portuguese interpreter.

Carlos had also complained of severe depression. Cargioli said they had to repeatedly call the facility to ask for a medical evaluation for Carlos and the reinstatement of his medication and to advocate for his immediate release. In early May, Cargioli said, an outside doctor, who did not speak Portuguese, visited Carlos at the facility and concluded that he had also developed diabetes while detained. Interpretation wasn’t provided, so the physician talked to Carlos in Spanish and used images from Google and a translation app to prescribe him a diet. Carlos was put back on medication for high blood pressure and had to be monitored for risk of kidney failure. (According to the California DOJ report, Imperial only had one physician and two nurse practitioners working full-time and only 4 percent of detainees were receiving mental health care as of June 2019.)

With Carlos’ medical records in hand, on May 8, Cargioli called the deportation officer’s supervisor directly. Four days later, ICE authorized his release on parole without a bond. “He may not have ever been released, and he could have quite literally died,” Cargoli said. “It shouldn’t have to take a managing attorney to speak to a supervisor to get someone to take a human being’s life seriously. It speaks volumes about what could be happening at detention facilities all across the United States.”

Since February, ICE has reported 9,029 confirmed cases of COVID-19 and at least eight deaths among detainees, a figure advocates warn is likely an undercount because it doesn’t account for people who had contracted the disease in detention but might have passed away after being released. About 1,000 employees of private contractors operating ICE facilities have tested positive, including at least six staff members at Imperial. According to a Detention Watch Network report from December, ICE facilities contributed to more than 245,000 cases of community spread of the disease nationwide.

Despite facing public pressure from advocates, doctors, and legislators to release immigrants at higher risk of falling ill or dying from COVID-19 in detention, former acting director of ICE Matthew Albence said “releasing non-violent immigrants to protect them from being infected and sickened with coronavirus” could send the wrong message about the enforcement of immigration laws and be a “huge pull factor” for migrants to cross borders.

ICE has reportedly released thousands of detainees. Between February 2020 and January 2021, the average daily detained population plummeted from 37,876 to a little under 15,000. On its website, the agency says it has let 2,661 people go as a result of court orders—510 from detention centers in California—many of which they are “actively litigating.” That includes a ruling in a federal class action lawsuit ordering ICE to identify and protect vulnerable immigrants in its custody. On appeal, a government attorney argued the judge’s decision was based on anecdotal evidence and put the agency “in a tough place to be.”

In July, a district court denied the ACLU’s April lawsuit to release at-risk immigrants detained at Imperial. The federal judge called the facility “a lone bright spot for Imperial County,” arguing that it had successfully implemented preventive measures to avoid a similar “calamity” to Otay Mesa Detention Center in San Diego, one of the detention centers hardest hit by the coronavirus outbreak. At the time, only two detainees had tested positive at Imperial. As of late January, the number has gone up to 23 confirmed cases and 4 currently under isolation or monitoring, according to ICE’s data.

The House Committee on Homeland Security released a report in September concluding that “ICE has set the stage for outbreaks at its facilities.”

“Instead of prioritizing bed space, ICE needs to put the health of its migrants in its care first,” Chairman Rep. Bennie G. Thompson (D-MS) said in a statement. The House Committee also noted that ICE facilities demonstrated “indifference” to the mental and physical health of migrants and failed to meet basic standards of care that are “a matter of life and death for migrants and employees.”

In addition, one of the most common complaints from the more than 400 detainees interviewed for the report was the lack of access to an interpreter and translation services. Migrants at California’s Otay Mesa said that those who spoke languages other than English or Spanish were subject to more abuse.

“One of the hardest things is to watch the system re-traumatize families and individuals and not being able to be face-to-face with my clients, which is what they deserve,” says Kate Goldman, manager of the Center for Latin American and Caribbean Studies at Brown University. She has worked as a translator for 20 years and is currently head of academic and university partnerships for Respond Crisis Translation. “When they can’t see you or feel anything other than your voice, it just makes everything that much more difficult. It also makes it even more crucial to have a skilled interpreter because every word has more weight.”

After his release in May, Carlos reunited with his sister and nephews, who had already been freed and moved in with a family friend on the East Coast. He is attending therapy sessions and has been prescribed medication for depression and anxiety, on top of sleeping pills. Some nights he has nightmares that he’s still in detention, and wakes up screaming. He’s still being treated for high blood pressure and diabetes. He says he has lost weight like a “deflated balloon.”

Carlos has found work cleaning gardens and backyards and is waiting for his main asylum hearing in September. One of his goals is to learn how to read and write. “To have never been arrested in your country and then being stuck in a place where no one speaks your language…I suffered a lot,” he says. “It felt like an eternity, like I would never leave.”