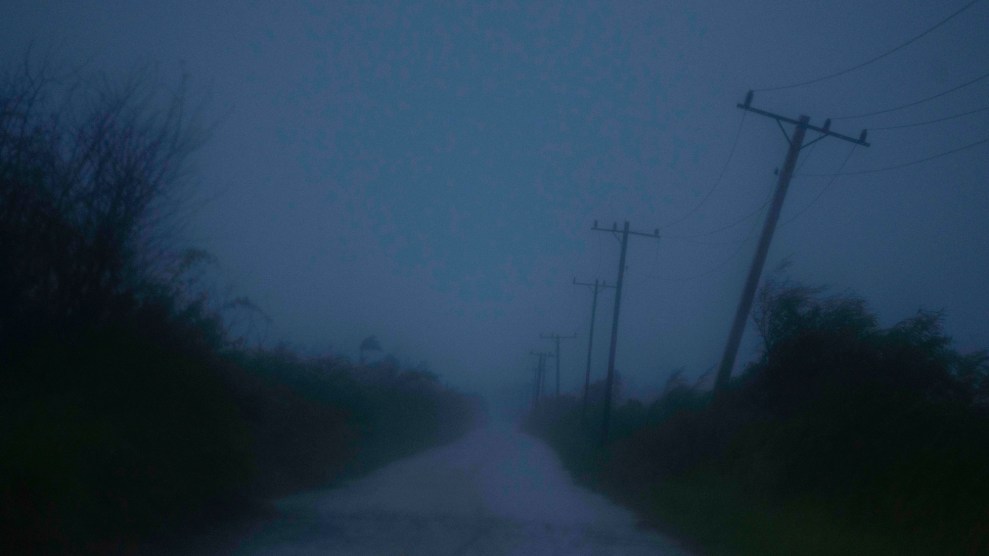

Jake Bittle/Grist

This story was originally published by the Grist and is reproduced here as part of the Climate Desk collaboration.

More than 72 hours after Hurricane Ida made landfall, plumes of dark black smoke were still rising from four towers at the Shell plant in Norco, Louisiana. Enormous flames billowed out of these towers in the heart of the petrochemical region known as “Cancer Alley,” and a thick smudge of smoke floated across the sky away from the plant.

The refinery has a history of significant flaring and compliance issues. In the last few years, the US Department of Justice and the Environmental Protection Agency have fined it for flaring more than allowed—and the facility has run into trouble with state authorities for failing to prevent emissions of sulfur dioxide and other toxic chemicals.

At least as of Thursday, it remained unclear when the flaring—where plants release gases into the air, often to relieve pressure and ensure safety—would stop.

“As a result of impacts related to Hurricane Ida, Shell’s Norco Manufacturing site is without electrical power,” said Cindy Babski, a spokesperson for Shell. “While the site remains safe and secure, we are experiencing elevated flaring. We expect this to continue until power is restored.”

In response to a series of follow-up questions, Babski confirmed that the facility relies on power delivered from Entergy, the utility that serves part of Louisiana, Mississippi, Texas, and Arkansas, which has said it may be multiple weeks before power returns to the New Orleans metro area. Babski said the company did not have a timetable for restoring power to the plant.

It’s unclear exactly what the facility is flaring and how much of it is being spewed into the air. The company is required to report unusual flaring activity to the Louisiana Department of Environmental Quality, the agency responsible for overseeing air quality in the state. A spokesperson for the agency told Grist that since the department’s records office had suspended normal operations due to the hurricane and loss of power, they weren’t sure if Shell had submitted flaring reports.

On the ground, residents noticed the increase in flaring. One resident in the nearby subdivision of Ormond Estates, who identified himself as Brad and was in the process of clearing debris from his yard, told Grist, “That’s not normal. That’s an ‘oh shit’ thing.” Julie Dermansky reported for DeSmog that many residents in the town of Norco said they’d never seen such significant flaring at the site. “That’s not normal. That’s an ‘oh shit’ thing.”

Increased flaring has become an annual occurrence during hurricane season. When Hurricane Harvey hit the Texas coast in 2017, about 40 petrochemical plants released about 5.5 million pounds of pollutants into the atmosphere. During Hurricane Laura last year, a Grist analysis found facilities in Texas flared more than 4 million pounds of excess pollutants.

On the one hand, flaring is a necessary evil to ensure the safety of operations. During hurricanes, when wind speeds top 130 miles per hour and there is potential for flooding, a refinery’s equipment is more likely to malfunction, and plant operators may abruptly need to shut down operations, forcing them to find a way to empty the equipment of any petrochemicals currently being processed. As a result, refineries often burn tens of thousands, if not millions, of pounds of pollutants to avoid the dangerous buildup of toxic chemicals.

These flares can also be avoided with adequate planning and preparation. By shutting down operations in a controlled manner well ahead of the hurricane making landfall and installing equipment that prevents excess flaring, refineries can prevent enormous pollution events during hurricanes.

“Refineries and chemical plants have kept getting better at reducing their everyday emissions,” said Dan Cohan, a professor at Rice University who has studied fossil fuel infrastructure. “We’ve gotten to a point where an enormous proportion of emissions happen during these startup, shutdown, and upset events,” such as when facilities lose power or a piece of equipment breaks.

In the aftermath of Ida, flare fires could be observed at several major facilities in the New Orleans area. The Norco smoke in particular was darker and more voluminous than the smoke rising from several other plants, including the nearby Valero and Marathon complexes. Cohan said that given the dark color of the smoke coming from Norco’s towers, he imagined many of the flared compounds were toxic.

Cohan said that most plants are required to have some kind of backup power source so they can avoid flaring, but that Shell’s backup didn’t seem to be sufficient. “The challenge at these sites is that you’ve got hundreds of chemical processes occurring with dozens of toxic compounds, all of them requiring electricity to keep running properly,” he said. “There’s a lot that can go wrong.”

Norco’s abnormally voluminous flaring may be explained by its long and checkered history of noncompliance with environmental rules. In 1988, a massive explosion at the site killed seven workers and injured 42 others, kicking off a yearslong environmental justice campaign by the residents of Diamond, a small community sandwiched between the Norco facility and another Shell plant. More recently, in 2018, after officials discovered that Shell had modified four of the company’s flares illegally to emit significantly more emissions, the company entered into a settlement with the EPA and Justice Department. As part of the settlement, Shell is required to spend $10 million on upgrades to reduce emissions from the four flares. The settlement also required the company to reduce the amount of waste gas it sent to the flares and pay $350,000 in fines. A Shell spokesperson said all upgrades required under the consent decree have been completed.

The Norco facility has also come under scrutiny for emitting high levels of benzene, a toxic carcinogen. A 2020 analysis by the Environmental Integrity Project found that the facility exceeded a federal threshold for benzene levels that is safe for human exposure for most of 2019. By the end of the year, however, the company was able to reduce its benzene emissions and meet health standards.

This year the facility ran into trouble with environmental authorities again. In June, the company emitted a slew of toxic chemicals, including sulfur dioxide, toluene, and volatile organic compounds into the atmosphere. Although the company reported it to the Louisiana environmental agency as an unpreventable event, the agency determined that the release was preventable. Staff forwarded the incident to enforcement officials within the department to review.

Despite Shell’s assurances that the Norco plant is “safe and secure,” several sections of the plant appeared to be inundated with the remnants of flash flooding from Ida, with water sitting more than two feet high in many places. At the front entrance of the plant on Highway 61, a security guard threatened to prosecute a Grist reporter for taking photographs of the flooded site.“We have cameras and can take down your plate number,” she said.

The Norco facility sits right along the Mississippi River, occupying some of the highest land in the parish. Thus, it enjoys much better flood protection than many nearby residential areas. A study by Darin Acosta at the University of New Orleans found that the Norco plant and the nearby Shell Motiva refinery occupy almost 75 percent of the high ground in St. Charles Parish, with the result being that lower-lying communities on the edge of Lake Pontchartrain bear the brunt of storm surge flooding.

Furthermore, Norco and other plants on the east bank of the Mississippi are protected from river flooding by a 20-foot river levee. Government officials can also open the nearby Bonnet Carre Spillway during times of high water to prevent the Mississippi from overtopping its banks, making it very unlikely that the river would overtop the floodwalls and enter the site.

Even so, the riverside land beneath the plant is low-lying and has poor drainage, which means that flash floods and heavy rains from storms like Ida cause water to pile up fast and stay put for a long time. Shell didn’t respond to a question about how the Ida flood had affected the facility, but earlier this year the company reported flood-related equipment failure to the Louisiana environmental agency. In March, after heavy rainfall, an oil sump at the plant was “overwhelmed and overflowed” into the surrounding area.

The finer details of Ida’s impact remain unclear, but the waterlogged plant site and the plumes of black smoke are a testament to just how risky oil production in the Gulf Coast can be. The Shell facility and other plants around it all seem to have survived the storm, and chances are they’ll still be there for the next hurricane.

The question is what happens when that storm strikes.