A person promotes abortion pills with boxes containing a quick code providing information on access to abortion pills outside the Supreme Court.Chris Kleponis/Sipa/AP

More than half of all abortions in the United States are currently performed by taking a set of pills. The first, mifepristone, interrupts the hormones needed to continue a pregnancy; the second, misoprostol, expels the contents of the uterus. For decades, the FDA has approved both drugs to be used together to end pregnancies before 10 weeks. Over the years, the agency has repeatedly honed its regulations of mifepristone, setting specific regulations on who may prescribe it, and how it can be dispensed.

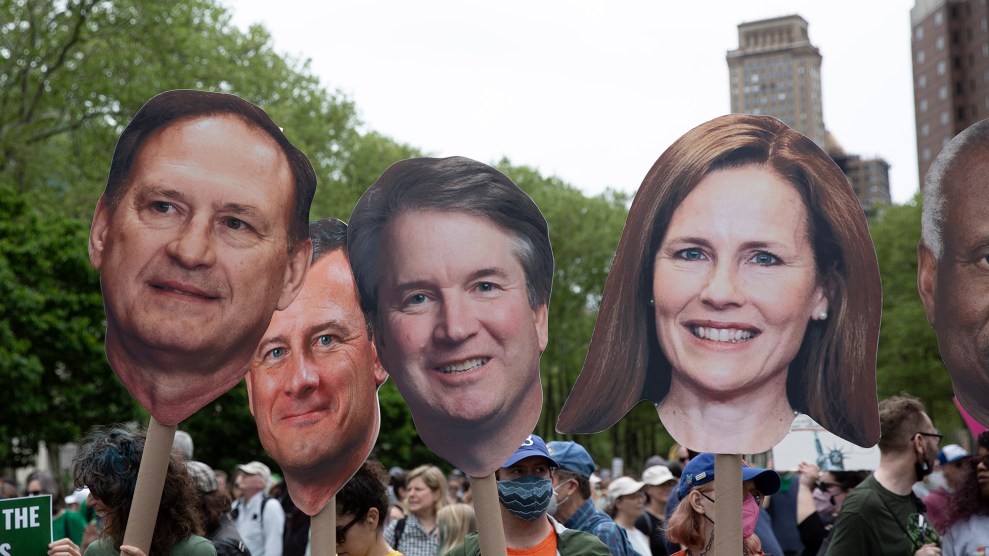

But today, the Supreme Court’s decision in Dobbs v. Jackson Women’s Health Organization cleared the way for states to enact abortion bans, including prohibiting medication abortion. But do states really have the power to ban a medication approved and regulated by the FDA? This open question is poised to become an important new front in the legal wars over abortion, now that Roe v. Wade has been lost, according to Rachel Rebouché, interim dean of Temple University’s law school.

Making this question more urgent, in reaction to the Supreme Court’s decision this morning, Attorney General Merrick Garland issued a statement saying the Justice Department “will use every tool at our disposal to protect reproductive freedom.” One of those tools: The constitutional principle of “preemption,” which could theoretically be applied to stop states from banning abortion medications, because the FDA already allows them.

It’s something that, in a paper earlier this year, Rebouché and her colleagues argued the federal government could do in the very scenario we’re faced with today.

Now, it looks like the attorney general agrees with them. “We stand ready to work with other arms of the federal government that seek to use their lawful authorities to protect and preserve access to reproductive care,” Garland said in his statement today. “In particular, the FDA has approved the use of the medication Mifepristone. States may not ban Mifepristone based on disagreement with the FDA’s expert judgment about its safety and efficacy.”

I called up Rebouché to learn more about what the attorney general’s statement signals for the legal battles to come. Our conversation has been condensed and edited for clarity.

What’s the attorney general saying here?

So the attorney general is offering support for an argument around “preemption.” Under the Supremacy Clause of the Constitution, when the federal government speaks on an issue, it “preempts” state laws or state policies that contradict the federal government.

The idea is that Congress gave the FDA the authority to regulate the safety of drugs. Taking a drug off the market, when the FDA has decided it is a drug that is safe and should be on the market, contradicts the FDA decision making.

So Garland is arguing that states can’t ban mifepristone because the FDA has permitted it.

That would be the idea. The FDA has spent a lot of time evaluating the safety and efficacy of mifepristone—the first drug in medication abortion, and the only drug that’s approved by the FDA to terminate a pregnancy.

And the regulation of mifepristone has been so exceptional. It’s similar, in its safety profile, to something like penicillin; it’s 10 times safer than Viagra. But in comparison to other drugs with the same safety profile, it has so many more restrictions. Many people believe that the strict restrictions on mifepristone reflect political concerns more so than concerns around the safety of the drug itself.

In short, [the preemption argument says that] when the FDA uses its statutory power to restrict access, to determine that only certified providers can prescribe a drug—it is the last word on the safety and the availability of a drug.

Why is it so notable that Garland made this statement today, as we prepare for half the country to make abortion illegal?

If FDA policy preempts state abortion law for medication abortion, it would create an exception in state bans across the country. The consequences could be profound. Twenty-six states could ban abortion, but they’d have to permit the distribution of mifepristone, coupled with misoprostol, for terminating pregnancies before 10 weeks.

That would create a huge loophole in state abortion bans—if courts agree with Garland. Where do the courts come down on this question?

It’s not a situation that’s been settled by the courts. It’s an underdeveloped area of law, because most states don’t try to ban drugs that the FDA approved. When Massachusetts tried to ban and then limit the availability of a certain opioid, a federal district court said that Massachusetts was preempted because the FDA had allowed the drug with other restrictions.

Should we expect more cases on the issue now that Roe has been overturned?

This idea is already being pressed in one court in Mississippi. GenBioPro, the generic manufacturer of mifepristone, has sued the state under a preemption doctrine. Mississippi’s regulation of mifepristone differs from the FDA in requiring, for instance, a person pick it up at a health care facility. We don’t know how that case will turn out yet.

And certainly the federal government could assert its own preemption authority in court—the FDA, represented through the Department of Justice.

Let’s war game this out a little. If lawsuits are filed, either by the federal government, or by manufacturers, they’d go to federal district courts, and given the lack of case law, it’s hard to predict which way they’ll rule. Potentially, could this issue go up to the Supreme Court?

It certainly could. If, for instance, the Ninth Circuit disagrees with the Fifth Circuit about whether FDA policy preempts [state law], that’s a circuit split the Supreme Court would resolve.

What’s really interesting about the question is that the Supreme Court—which just ruled today that its states’ prerogative to decide questions about abortion—would then be asked to decide if a federal agency gets to trump state law.

The Supreme Court has not been necessarily friendly to protecting agency power. The Court this term is hearing a case about what the Environmental Protection Agency can or cannot do. There’s been a series of cases suggesting that federal agencies shouldn’t be accorded deference, as they had in the past. A federal district court in Florida applied that kind of reasoning to say that the CDC shouldn’t be accorded deference to require masks on planes.

Could there be unintended consequences of pursuing this legal argument?

If you think about the opioid example, Massachusetts believed that the opioid in question was more dangerous than what FDA policy on it had suggested, and it sought to solve that problem. There could be the unintended consequences, in that states that want to have stricter control on drugs than the FDA might be precluded from doing so.

Of course it’s important to pursue strategies while being mindful of what their future consequences could be outside of the area you’re thinking about right now. But I also think that what’s refreshing about the attorney general’s statement is that we are now in uncharted territory. As of today, and going forward, the legal landscape becomes even more complex, the landscape for abortion access becomes much harder to navigate, even though it was very hard to navigate before. If the federal government wants to try to open access, then this is one means to try.

We don’t know what’s going to be successful. It may not win in the Supreme Court, if it gets there. It may take years to get there. It’s not clear. But the other option is not doing it. And not acting has its own consequences, too.