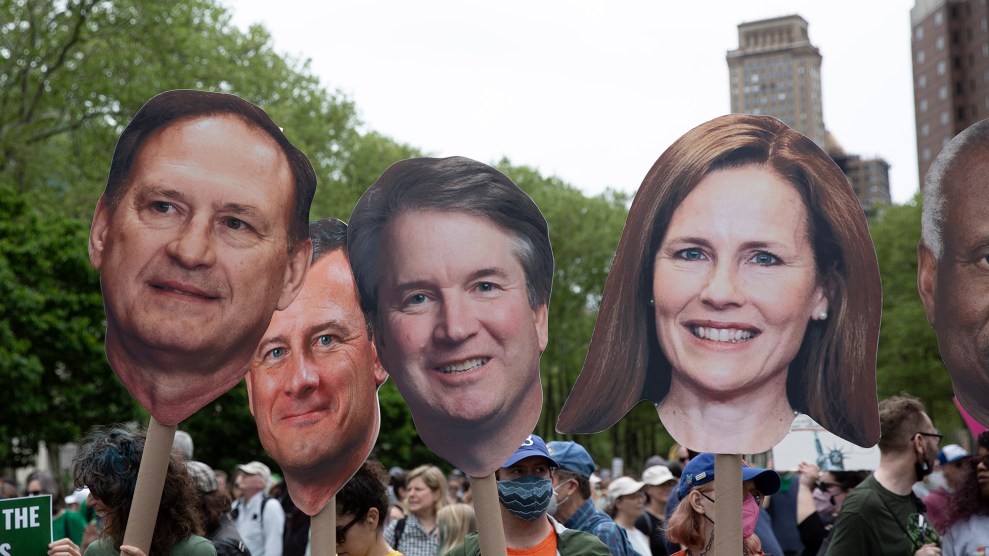

Protesters hold cardboard cutouts of the Supreme Court Justices that support overturning Roe v. Wade. Gina M Randazzo/Zuma

Some Supreme Court opinions are hard to unpack. Justice Samuel Alito’s majority opinion striking down Roe v. Wade, though, can be summarized in just a few words. “The Constitution does not confer a right to abortion; Roe and Casey are overruled; and the authority to regulate abortion is returned to the people and their elected representatives,” he wrote.

The first two clauses are the news, but the last line, more than just a quick housekeeping note, is the story of how we got here. The defeat of Roe was made possible by cutting corners and seizing every advantage in an undemocratic system—it was a redistribution of power bordering on theft.

There are layers to the crisis of legitimacy here, but the most obvious one is this: Of the six justices who voted to end the constitutional right to an abortion—Chief Justice John Roberts’ caveats are the sort of thing that only he could care about right now—five were appointed by a president who first came to office after losing the national popular vote. In the cases of Roberts and Alito, the president who appointed them was himself placed in office with the help of the Supreme Court. And Neil Gorsuch owes his job not just to Donald Trump, but to a Senate that blocked a Democratic president from filling the seat for a year.

In returning power to the states—or Congress—the justices are now returning the ball to uneven playing fields, which in some cases they have played a part in creating. The Senate is undemocratic in its composition—as Mother Jones CEO Monika Bauerlein noted earlier this year, Republican senators represent 41 million fewer people than Democratic senators—and in its ethos. It is bound by an anti-majoritarian set of rules, and filled with people (including some Democrats) who simply don’t believe that the chamber should swing in accordance with the national will. The Supreme Court has gutted the Voting Rights Act at the federal level, inviting states to attack the franchise as they see fit. And in places like Wisconsin, Democratic-leaning electorates have been simply unable to elect Democratic legislatures because of an impenetrable gerrymandering wall constructed more than a decade ago. The Supreme Court has largely given the green light to such efforts in Wisconsin and other states. Abortion rights are now in the hands of “the people and their elected representatives,” Alito says—but those aren’t the same things, and he’s helped ensure that the latter isn’t bound as closely to the former.

One of the defining stories of the last two decades is the transfer of power from a minority of the electorate to an all-powerful assembly of justices, who in turn have bestowed that power upon the most reactionary of states; it’s like money-laundering for democratic legitimacy—a crowning achievement for an age of conservative minority rule.