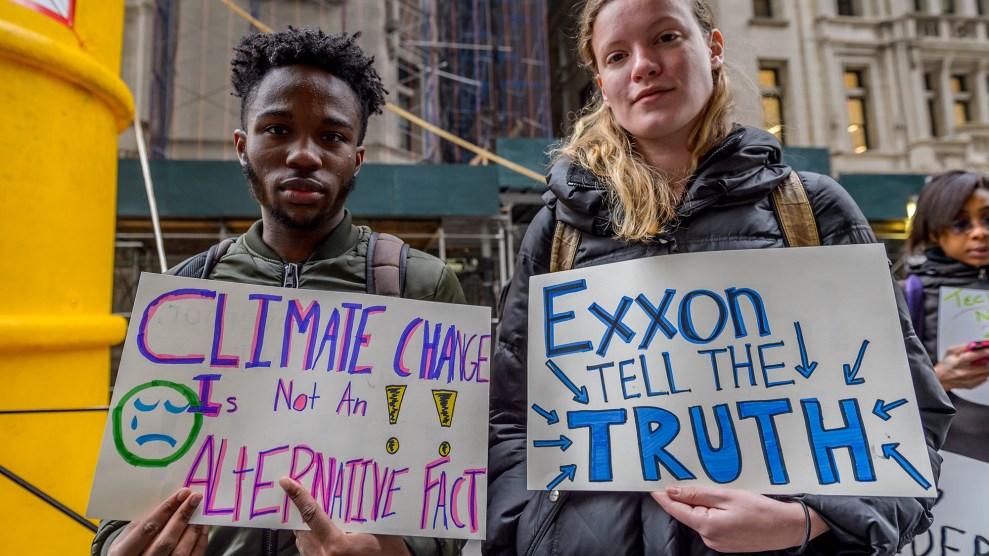

Climate justice activists at the Cop26 Climate conference in Glasgow, November 2021. A recent report notes the increase of climate change disinformation spreading on social media, particularly around the time of Cop26. Andrew Milligan/PA Wire/ZUMA

This story was originally published by the Guardian and is reproduced here as part of the Climate Desk collaboration.

Climate policy is being dragged into the culture wars with misinformation and junk science being spread across the internet by a relatively small group of individuals and groups, according to a study. The research, released on Thursday, shows that the climate emergency—and the measures needed to deal with it—are in some cases being conflated with divisive issues such as critical race theory, LGBTQ+ rights, abortion access, and anti-vaccine campaigns.

The study, published by the Institute for Strategic Dialogue and the Climate Action Against Disinformation coalition, found that although outright denials of the facts of the climate crisis were less common, opponents were now likely to focus on “delay, distraction, and misinformation” to hinder the rapid action required.

“Our analysis has shown that climate disinformation has become more complex, evolving from outright denial into identifiable ‘discourses of delay’ to exploit the gap between buy-in and action,” said Jennie King, head of climate disinformation at the Institute for Strategic Dialogue.

The report looked at social media posts over the past 18 months and particularly around the Cop26 climate summit in Glasgow last year. It found that the urgent need for wide-ranging mitigation and adaptation strategies were continually downplayed or condemned as unfeasible, overly expensive, disruptive or hypocritical. And it identified a number of specific “discourses of delay,” including:

• Elitism and hypocrisy: These posts focused on the alleged wealth and double standards of those calling for action, and in some cases referenced wider conspiracies about globalism or the “New World Order.” The study identified 199,676 mentions of this narrative on Twitter (tweets and retweets) and 4,377 posts on Facebook around the time Cop26 took place

• Absolution: It found 6,262 Facebook posts and 72,356 tweets around Cop26 which absolved one country of any obligation to act on climate by blaming another. In developed Western countries this often focused on the perceived shortcomings of China and, to a lesser extent, India, claiming they were not doing enough so there was no point in anyone acting.

• Unreliable renewables: Over a longer period—from January 1 to November 19, 2021—the study found 115,830 tweets or retweets were shared, alongside 15,443 posts on Facebook, that called into question the viability and effectiveness of renewable energy sources.

The report found that the most prominent anti-climate content along these lines came from a handful of influential pundits, many with verified accounts on social media. Analysis of 16 accounts “super-spreading” climate misinformation on Twitter revealed 13 sub-groups that largely converged around anti-science and conspiracy communities in the US, UK, and Canada. It said many “influencers” in this group originally came from a scientific or academic background and some were previously involved in the green movement.

It added: “This allows them to present as ‘rationalist’ environmentalists and claim greater credibility for their analysis, while continually spreading the discourses of delay and other misinformation or disinformation. It also gives them significant appeal online and the potential to galvanize far broader audiences, since they are frequently invited by conservative media outlets as ‘climate experts’.”

The report called for an internationally agreed definition of climate misinformation and disinformation, adding that tech companies should restrict paid advertising and sponsored content from fossil fuel companies and known front groups or individuals that repeatedly fell short of that standard.

King said: “Governments and social media platforms must learn the new strategies at play and understand that disinformation in the climate realm has increasing crossover with other harms, including electoral integrity, public health, hate speech and conspiracy theories.”