Patients entering the bright third-floor offices of Houston Women’s Reproductive Services used to follow the familiar steps for a routine medical appointment: check in, get your blood pressure taken, have other vitals examined. But for the past nine months, the typical rhythms and protocols have been completely upended. These days, patients seeking abortion care are rushed straight to an ultrasound—lab work comes later. They are often overcome with palpable anxiety. “Our patients are absolutely panicked when they come in. They are nervous wrecks, they are trembling with fear,” says administrator and founder Kathy Kleinfeld. “It’s heartbreaking. So we try to get them the answers they need right away.”

The answer they need immediately is if they are within the narrow six-week mark and can qualify for an abortion in Texas under a draconian law, Senate Bill 8, that bans abortion care in the state once embryonic cardiac activity is detected. “We are all holding our breath during every sonogram,” says Kleinfeld.

The small staff of four full-time employees is also consumed with urgency and anxiety; if abortion care takes place past the strict timeframe, that could mean costly and destructive career-ending lawsuits.

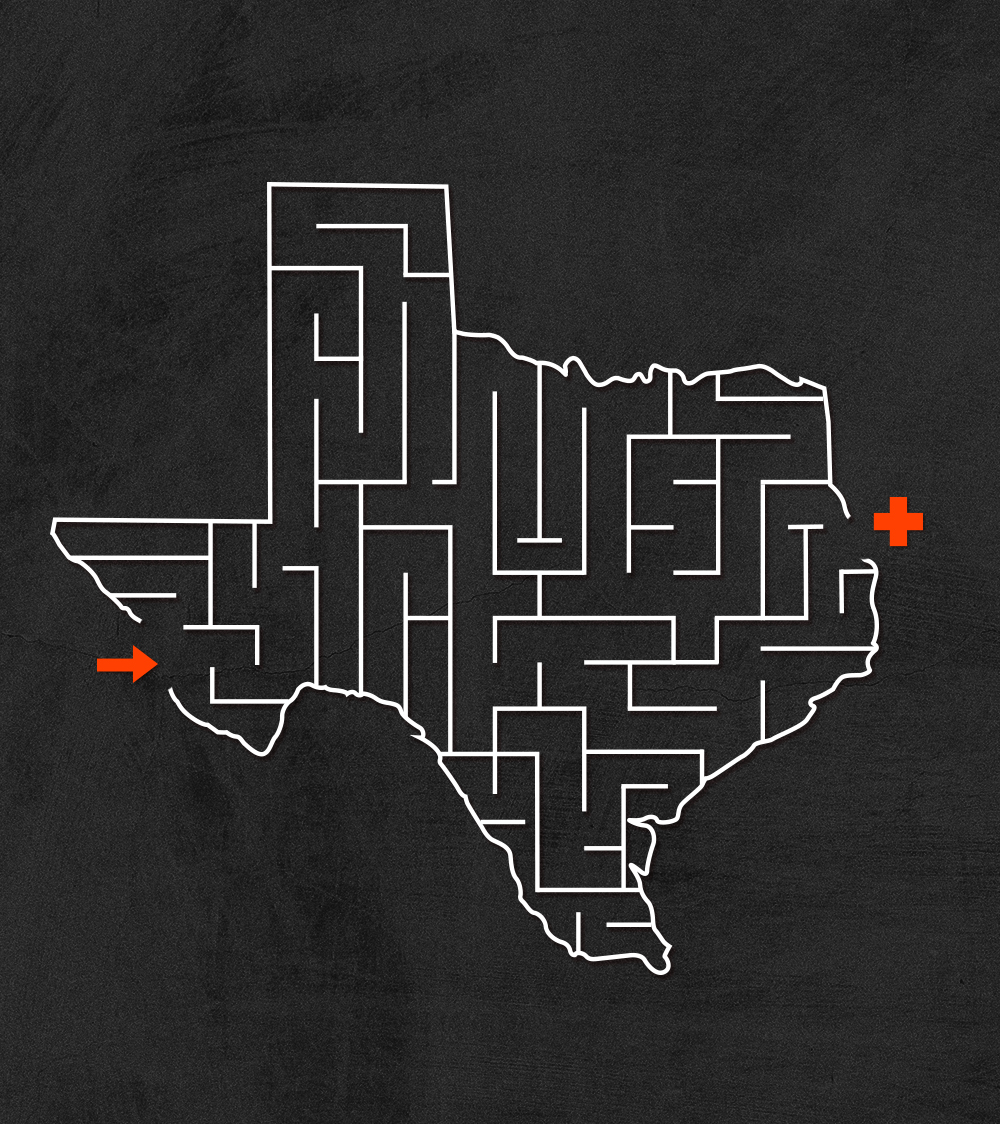

There are some who are within the window and can obtain abortion care at the clinic. They usually “burst into tears” of relief, says Kleinfeld, though they still have to wait 24 hours following the ultrasound, as mandated by another 2011 state law. But then, there are the more than 300 in-person patients—and thousands of callers—who the clinic has been forced to turn away since the ban took effect. These are the people, Kleinfeld says, who feel “devastated” and “deeply shocked.” Some end up confused and dazed, burdened with processing how and even if they can secure the resources and manage the logistics required to make the trek out of state. How is it possible to get child care, time off work, and money for transportation and lodging? Providers and advocates resoundingly stress it is low-income Texans and people of color who have been disproportionately affected by the severe law and who are most likely to carry unwanted pregnancies to term.

As a result, Texas clinics have been transformed into what are essentially somber travel agencies. Since September of last year, when SB 8 took effect, an average of nearly 1,400 Texans traveled out of state for abortion care each month, a figure nearly equivalent to the number that traveled every year between 2017 and 2019, according to the Texas Policy Evaluation Project. Some are forced to travel hundreds, even thousands, of miles for an abortion, causing a “domino effect” by delaying care for others at health clinics across the country, according to the Guttmacher Institute.

Kleinfeld now refers to her clinic staff as “navigators,” as they are tasked with shepherding distraught patients to medical care far from home—helping them find transportation, lodging, and even meals. “We are like de facto travel agents because of this law,” she says. “Our secondary—and even primary—jobs now are to truly be navigators.”

One of these navigators can’t believe how her work has changed—and feels shock at history repeating itself. As a college student at the University of Texas at Austin 50 years ago, she helped guide people in Texas to abortion access prior to Roe. “It’s absolutely scary watching this happen again,” says Kitty, who asked to be identified only by her first name. She hears the same “desperation, sadness, and anger” as she did when she was assisting abortion-seeking Texans in the late ’60s and early ’70s. “It’s unbelievable.”

It is also a harbinger of what is to come across the country if, as expected, the Supreme Court guts the landmark 1973 ruling in the coming weeks, which would be followed by 26 states certainly or likely banning abortion care. “All the adjustments we’ve had to make,” Kleinfeld explains, “are unfortunately a preview of what clinics in other states may soon need to do.”

Living under what was the nation’s most restrictive abortion law for most of the past year, Texas clinics have been forced to adapt and transform their practices, or face SB 8’s punitive consequences. Erroneously dubbed a “heartbeat” bill by anti-abortion advocates, the law offers no exceptions for rape or incest and is, in effect, a near-total ban as it cuts off abortion care before most people are even aware they are pregnant. Its novel private enforcement mechanism empowers any individual—including anti-abortion vigilantes with no connection to the patient—to sue abortion providers or anyone who “aids or abet” care for damages of at least $10,000, effectively chilling clinic operations. The law has already inflicted irreparable harm in a state that’s home to 10 percent of the country’s reproductive-age population.

While medication abortion and telehealth may seem like an ideal solution for abortion-seeking Texans, particularly those who cannot travel, state lawmakers added major barriers to that option as well. Senate Bill 4, which took effect in December, bars the mail delivery of abortion medication and shortens when a patient can take that medication from 10 weeks to seven weeks of pregnancy, despite the fact that the Food and Drug Administration lifted federal mail restrictions and approved use for up to 10 weeks; SB 4 instead requires doctors to give the pills in-person. Providers who violate the law could be saddled with a state felony, a $10,000 fine, and up to two years in prison. Kleinfeld says requests to travel out of state for telehealth services are rare. (Of course, some Texans have not let SB 4 prevent them from accessing self-managed abortion online, turning to channels outside the US health care system; after SB 8, Austria-based provider Aid Access saw a sharp rise in Texans requesting abortion pills.)

So over the past few months, Kleinfeld and her team have become experts on, as she puts it, the “complex web” of abortion hurdles in surrounding Southern states and beyond. She has memorized a list of restrictions, which she expertly rattles off: If a patient wants care in Arkansas, they’ll need to make two trips to the clinic and wait 72 hours between the ultrasound and the procedure; New Mexico doesn’t have a waiting period; in Louisiana, they must wait 24 hours and make two clinic visits, and so on. When we speak in mid-May, Kleinfeld tells me she needs to be vigilant about shifting laws—particularly in Oklahoma, where nearly half of displaced Texas patients were getting abortion care. At the time, a six-week ban, modeled after Texas’, was in effect in Oklahoma, drastically narrowing a crucial pipeline for abortion-seeking Texans and forcing Kleinfeld to further redirect patients. In the weeks since, a total ban has also been put in place there, dealing a final blow to that line of care. “It’s been so important to know the laws in other states as we try to arm patients with the most accurate information to navigate access,” she says.

One strategy for implementing the most effective “travel agency” has been to strengthen lines of communication with abortion funds and out-of-state providers. Clinic staff sometimes texts other clinic staff directly on their personal cellphones to ask how long patients will need to wait for the next appointment; other times they juggle a number of different Slacks and listservs (“There are so many,” remarks Kleinfeld) among providers across the nation. Collectively, they all feel an unprecedented sense of solidarity in their mission to connect patients to care.

“It’s never been more imperative to network with outside clinics and abortion funds,” Kleinfeld explains. “That’s certainly been a big change, we now need to be in constant communication.”

Whole Woman’s Health, which operates four clinics in Texas and five in other states, has made a similar pivot. Its Texas clinics have seen approximately 50 percent fewer patients since SB 8 took effect and a rise in those seeking care outside the state. So Amy Hagstrom Miller, the organization’s president and founder, has hired new staff solely focused on helping patients get appointments across state lines. They call this new travel assistance service the “Abortion Wayfinder” program, which seeks to streamline and facilitate a sometimes complicated process. By networking with other abortion support groups, Whole Woman Health’s staff members make appointments in other states on behalf of displaced Texas patients, including at its own Virginia and Minnesota sites. If needed, Whole Woman’s Health will dip into its own abortion fund, Stigma Relief, and coordinate with national and local abortion funds to provide financial support to cover the procedure, as well as travel and other logistics. Over the past few months, the program has helped 60 low-income patients, with $1,000 each.

Nonetheless, even with assistance, the financial burdens of travel and managing the logistics aren’t always easy for patients, especially those who are already struggling economically. Some don’t have credit cards, for instance, which makes booking hotels and flights more difficult; others have never taken an Uber before or boarded an airplane. One patient, says Hagstrom Miller, refused a flight to Alexandria, Virginia, as she had never flown before and couldn’t leave her children behind. Instead, she made the 26-hour drive from the border city of McAllen, with her whole family in tow. (These stressors are far from unique: Nearly 60 percent of those who have abortions are already parents, and of that number, a third have at least two children, according to the Guttmacher Institute.) Other providers note the difficulty in travel for undocumented residents navigating access amid in-state Border Patrol checkpoints. Minors confront other complications; some hotels, for instance, require guests to be at least 21 years old.

So what may seem like a straightforward journey from one place to another often becomes fraught with unexpected difficulties and challenges, particularly for already vulnerable Texans. Hagstrom Miller explains that the need for the program was obvious to those who worked there, but the challenge was creating an infrastructure to support all of its various elements. “One thing has been very clear,” Hagstrom Miller adds. “When patients decide they want abortion care, they are very determined to be unpregnant.”

For transportation that doesn’t involve air travel, they are working to devise scalable ride-sharing programs with other groups. They also manage a database that keeps track of which airlines have the most reliable schedules and service and the team has developed relationships with hotels that specifically don’t stigmatize against abortion and even with sandwich shops in other states to help patients obtain meals—unusual roles they never thought they’d fill.

“I think we will see that some clinics will remain open without providing direct [abortion] services but will be there to support patients and do everything possible to help them get access to care in other states,” says Elizabeth Nash, who tracks state reproductive health policy at the Guttmacher Institute. “Texas clinics have already started figuring this out…It’s a real testament to the perseverance of these clinics.”

Working hand in hand with the clinics are abortion funds, which have long been on the frontlines of connecting low-income patients with access. They too have seen their operations change as they face unprecedented demand. Fund Texas Choice offers financial assistance to patients for transportation to clinics and has functioned as a de facto state travel agency since it started in the wake of House Bill 2, which shuttered half of Texas’ clinics and gave way to several “abortion deserts” in the massive state. (Although the multi-part state law was overturned by the Supreme Court in 2016, most of the defunct clinics have been unable to recover and reopen their doors, underscoring HB 2’s lasting impact.)

These efforts have only grown under SB 8. Before the law took effect, less than half of the 40 clients Fund Texas Choice served a month required out-of-state travel; today, 99 percent of the now 100 clients it serves monthly do, involving on average more than 1,300 miles roundtrip. As surrounding states continue to restrict abortion care, Fund Texas Choice program manager Sahra Harvin worries about how the increase in distance will in turn hike the average cost per client, especially amid rising gas and airfare prices. While the group was able to assist every caller before SB 8, call volume has jumped sixfold, and even after adding new staff, they are still unable to meet demand.

“We don’t need to imagine a post-Roe environment. We know firsthand what it looks like,” says Harvin. “We’ve seen how there are not enough hours in the day to help everyone that calls us, and that demand will likely rise. It should not be up to funds and practical support organizations to ensure the people of this state access essential health care—we are just filling the gap where the state has failed.”

Similarly, Texas Equal Access Fund, which operates in the state’s north, went from supporting a quarter of its callers in traveling out of state to almost 90 percent. The majority of clients seeking help from the Lilith Fund, which serves central and south Texas, are also now going out of state, which has led the group to increase the amount spent per client from an average of $348 in 2020 to $587 in the months since SB 8 took effect.

This is further hurting the most vulnerable Texans, including Black, Indigenous, and other people of color, people with disabilities, people in rural areas, young people, and undocumented people, who constitute most of these funds’ callers. Indeed, more than 70 percent of TEA’s callers are BIPOC, with Black women making up the majority of its client base. Most lack health insurance and, due to federal Medicaid rules and a Texas law that prohibits public and private insurance covering abortion, they must pay out of pocket.

“Abortion bans are systemic discrimination and racism in action—and the impact of SB 8 and other abortion restrictions have been extremely harmful to our most marginalized communities,” says Kamyon Conner, TEA’s executive director. “The added cost and logistics to go to another state make getting an abortion very hard for people who don’t have access to paid time off or are unable to take any time off to get care. We worry that people will just go without the care they need.”

Anti-abortion laws are “blatant misogyny and white supremacy in action,” echoes Lilith Fund executive director Amanda Beatriz Williams.

With the future sustainability (and job security) of Texas clinics up in the air—especially independent providers, which face a greater threat of closure—investing in building clinics elsewhere may turn out to be the most strategic path forward for the post-Roe world.

Some providers are already eyeing expansion in “safe haven” states that are working to enshrine abortion rights and even expand abortion access. In her office, Hagstrom Miller keeps a map of the US that outlines which states will likely protect abortion access if Roe is struck down. While she’s had it up since 2019, today it’s become indispensable. She uses it to explore where she might open a new clinic next; her team is currently evaluating cities in Illinois and North Carolina as possible options. After SB 8 went into effect, Whole Woman’s Health opened a new clinic in Minnesota, which is expected to be a safe-haven state; it’s situated near the Minneapolis–St. Paul airport for easier access for out-of-state patients. Today, some 30 percent of that clinic’s clients come from Texas, a figure that is expected to rise “drastically,” she says.

But Nash from the Guttmacher Institute stresses that not even people who live in those safe haven states are immune from the damaging policies of abortion-hostile states, since patient displacement is causing a ripple effect across clinics in all regions. “Despite what’s been happening in Texas, and now Oklahoma, it hasn’t seemed to quite penetrate into the public consciousness,” says Nash. “Some of that is because abortion is very stigmatized and some of that is because people don’t think these laws will affect them. But, in fact, what we are seeing is that what happens in one state causes disruption across the country. Providers from California to Maryland are seeing the effects of high patient volume, delayed wait times, and capacity shortages.”

While all the changes that Texas abortion clinics have been required to make have been exhausting, one of the most difficult and emotionally taxing parts has been turning away more and more patients while adhering to a law that directly contradicts their values and principles as compassionate medical providers. Beyond acting as travel agents, clinic directors say staff have become informal trauma counselors, as they interact daily with angry, terrified, confused, and desperate patients, some of whom are forced to continue pregnancies against their will in a state that has a tattered social safety and family planning net. In many cases, there is nothing staff can do for them other than to “listen, hold their hands, and dry their tears,” says Hagstrom Miller.

“You will feel immense guilt and grief as you are forced to carry out the state’s will against your own conscience,” she says, offering advice for other abortion providers. “The psychological and emotional impact this will have on you will be traumatic. But please remember, it is not your fault. There is no way to fully prepare other than to make time and space for the sadness.”

Kleinfeld says that in order to continue the work even while turning hundreds of clients away, she and her team try to focus on the individual victories—the patients who are able to get care within the narrow sliver of time still allotted by law. When we speak again in early June, she shares the story of a young woman who called her Houston clinic panicked since she believed she was eight-weeks pregnant and thus past the legal limit in Texas. Kleinfeld advised her to come in for an ultrasound anyway; it turned out the patient had miscalculated the date of her last period and was only five-weeks pregnant and able to receive abortion care at her hometown clinic.

“She was over the moon,” says Kleinfeld. “She was so relieved and so happy that she didn’t need to travel out of state…When a patient comes in and is actually within the legal limit, it’s like, ‘Hallelujah!’ Those moments help keep us going.”