All across the country, with its wildly uneven distribution of reproductive health services, anti-abortion protesters continue to wage a war of attrition against abortion access—often transforming the public spaces in front of clinics into hostile zones that clients must navigate in order to access essential care.

It will only get harder now that the Supreme Court has gutted Roe with its decision in Dobbs v. Jackson Women’s Health Organization. While abortion access has become increasingly difficult in recent years, particularly for marginalized communities in abortion-hostile regions, we will soon face the grim reality that abortion most likely will be banned in at least 25 states. (Oklahoma didn’t even bother to wait for the Supreme Court to institute such a ban, which the governor signed at the end of May.) At the same time, abortion clinics that still remain are anticipating more protests by emboldened and potentially more aggressive anti-abortion activists who are seeking to transform the nation into a unified abortion wasteland.

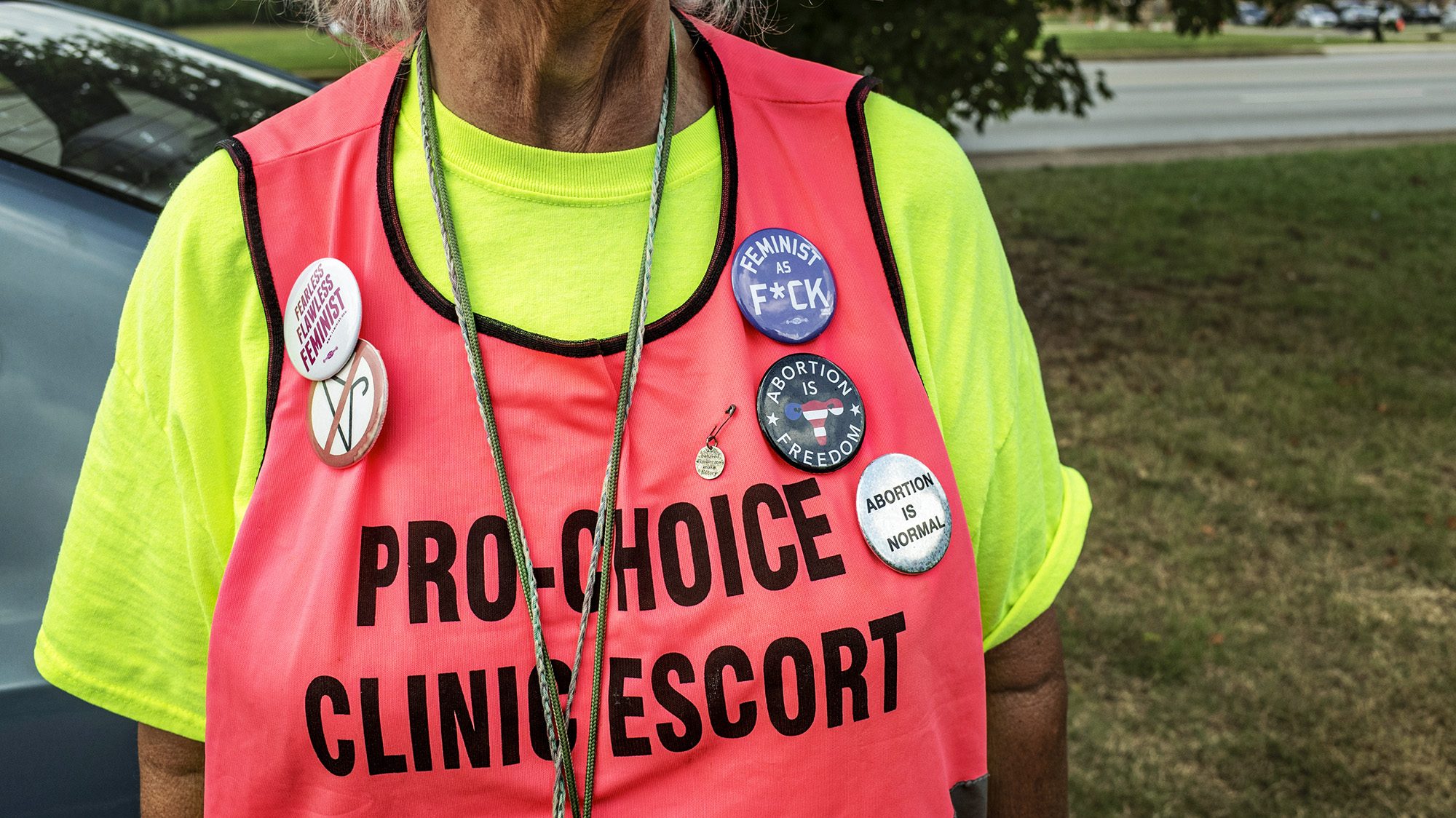

We have both witnessed what’s happening at these clinics but through different vantage points. a.l. Dawson has been a volunteer clinic escort at an urban reproductive health clinic, which has seen its share of violence over the years and is regularly besieged by protesters. However, this clinic is located in a state with a strong track record of supporting abortion rights and accordingly has not suffered the same kind of escalating attacks by anti-abortion forces that clinics in more abortion-hostile areas of the country have experienced in recent decades.

While working at the clinic, Dawson has navigated through protesters, leading those seeking abortions or other reproductive health services safely through the clinic doors. J. Shoshanna Ehrlich is a feminist legal scholar. (And, full disclosure, we are also married.) Ehrlich has studied the legal regulation of abortion, focusing on the gendered and racialized history of the nation’s abortion statutes, the abortion rights of minors, and the paternalism of the so-called “pro-woman/pro-life” antiabortion position, which positions women as the second victim of abortion.

But what does the experience of escorting clients look like through these dual prisms? Dawson recounts what took place over a typical two-hour shift this past winter, during which he sought to provide safe passage to anxious clients as they were confronted by well-organized anti-abortion protesters and so-called sidewalk counselors. Throughout Dawson’s on-the-scene account, Ehrlich weaves in the broader context of the anti-abortion movement’s oppositional tropes—specifically, abortion as murder, as reproductive trauma, and as racial genocide—and provides the intellectual context for the fear and harassment that clients, escorts, and providers endure on a daily basis in the contested spaces outside our country’s reproductive health clinics.

A clinic escort walks outside of the Planned Parenthood of Metropolitan Washington, D.C during a protest vigil sponsored by The Christian Defense Coalition and Priests for Life Carol Whitehill Moses Center.

Zach Gibson/Getty

On a sunny and chilly Wednesday morning, I make what has become a familiar walk from my home to the reproductive health clinic to begin my client escort shift. The clinic tries to have two volunteers for every weekday shift and three or four for the Saturday shifts. Often, it does not work out like that, and this is one of those times. I am on my own today.

Four years ago, I had just retired from my university teaching and research position, but I wanted to continue to be fully engaged in meaningful and progressive work, so I became a clinic escort. The attacks on women’s rights to make informed choices about their reproductive health were becoming more commonplace across the country. One thing I thought I could do was to offer some degree of safety for clients from the harassment they face as they enter a clinic.

In June of 2018, I filled out a clinic escort volunteer application and passed their background check. A month later I was informed I was accepted and went through a half-day training in September. Two weeks later I was on my first two-hour clinic shift with an experienced volunteer. Since that first shift, I have volunteered once a week, and sometimes twice a week, depending on the clinic’s staffing needs and my own schedule.

After walking six blocks, I see four protesters with signs standing on the curb 10 feet in front of the clinic entrance. The building is at the corner of a busy urban thoroughfare, and clients enter from the sidewalk. There is no clinic parking lot for clients. They either are dropped off in a car, take public transportation, or park at a public lot nearby.

I make no eye contact with the protesters as they stand with their signs chanting prayers. I take out my N-95 mask and put it on as I enter the clinic. I greet the two security guards near the metal detector, and we have a minute of friendly banter as I don my bright orange volunteer escort vest. The protesters have been relatively quiet so far, they say, but we all know that can always change in the blink of an eye.

The guards thank me for volunteering, and I reply with something like, “Right back at you.” Taking a deep breath, I tighten my mask, walk out the door, and begin my shift. I immediately survey the sidewalk scene. There are more protesters now. Two of them are positioned on each side of the entranceway to the clinic. Four more are on the curb in front and another two are at the corner where a side street meets the main thoroughfare. There is a roughly equal number of women and men. Most appear to be middle-aged and older; all are white.

One of the protesters holds a poster with a large image of a free-floating fetus and the message “When They Tell You That Abortion is a Matter Between a Woman and Her Doctor, They’re Forgetting Someone.” This poster of the fetus reminds me of why I do this work.

I move a few steps to the edge of the clinic’s property line until I’m just far enough so I can peer out to see foot traffic coming from both directions. In our training, we are told that protesters can’t cross over that line onto clinic property, but their shouting, singing, and prayers on a busy Saturday can sometimes be heard almost half a block away. This morning I hear them reciting The Lord’s Prayer in subdued voices.

As a general rule, escorts adhere to a non-engagement protocol, as they insulate and try to protect clients and clinic staff from the protesters and sidewalk counselors who have transformed the public space in front of clinics into a contested and hostile territory. In this regard, escorts are distinct from the often younger clinic defenders, who according to a recent New York Times article, “act more as counterprotesters” who deploy “loud and unapologetic tactics” in support of abortion providers

It is important to note that even though escorts are now commonplace, they haven’t always been an essential part of the clinic ecosystem. Following the emergence of radical direct action anti-abortion groups in the 1980s, such as Operation Rescue and the Pro-Life Action League, whose members had grown weary of efforts to upend abortion through more mainstream political pathways, reproductive health clinics became sites of increasingly confrontational protests and violent attacks. In response, as Lauren Rankin recounts in her 2022 book Bodies on the Line, clinics began to recruit volunteer escorts, who sometimes were drawn from state and local affiliates of the National Organization of Women, to help clinic staff and patients navigate these progressively more turbulent and dangerous spaces. Although this no longer seems to be a concern today, Rankin notes that during these early days “some clinic providers worried that having clinic escorts would actually inflame tensions by goading anti-abortion activists into bringing even bigger numbers to their front doors.”

As a general rule, escorts adhere to a non-engagement protocol, as they insulate and try to protect clients and clinic staff from the protesters and sidewalk counselors who have transformed the public space in front of clinics into a contested and hostile territory. In this regard, escorts are distinct from the often younger clinic defenders, who according to the New York Times, “act more as counterprotesters” who deploy “loud and unapologetic tactics” in support of abortion providers.

Their voices grow louder as they begin a new chant: “Holy Mary, Mother of God, save us from the sins of Hell.” Four protesters hold a crucifix with a string of rosaries and repeat the same refrain over and over again. One kneels, while the others stand. During the weekday shifts, virtually all the protesters appear to be Roman Catholic. On Saturdays though, there often is an evangelical bible group of Latinx families who come to sing and pray in front of the clinic.

I continue to try and avoid direct eye contact with them, but I shoot a quick glance to my right as they begin a new refrain, “Holy Mother, we pray for the souls of the murdered unborn…” These faces and voices are very familiar. I have seen and heard most of them repeating the same prayers and chants every week.

I walk back to the property line and adjust my mask, making sure it’s a tight fit for when unmasked protesters shout in my face. Their voices are quieter once more as they resume their prayers on both sides of the clinic entrance.

One of the protesters outside the clinic brandishes a sign with the classic image of a fetus, announcing, “When They Tell You That Abortion is a Matter Between a Woman and Her Doctor, They’re Forgetting Someone.” But let’s unpack what is happening here: The caption deploys three rhetorical moves intended to leave no question that the fetus is a human being. First, by identifying the fetus as “someone” who has been forgotten, the fetus becomes an individual, living child. After the bold-faced assertion, in smaller letters, the image is described as that of a “healthy, active intrauterine child,” which suggests that the only difference between a fetus and a child is the mere accident of geography—some children live inside the womb, others live outside it. Finally, the word “forgetting” implicitly positions the pregnant woman and the abortion provider as collaborating in the murder of this “someone,” motivated only by their own self-interests. In this rendering, abortion-seeking clients are cast as wrongdoers. Some anti-abortion leaders have over time rebranded pregnant women as victims who need to be protected from the “abortion industry”—a turn that interjected an overtly paternalistic leitmotif into this contested terrain.

This effort to make the distinction between a fetus and a child disappear is reinforced by the image in the poster. The fetus is bathed in a gentle light as it reaches imploringly towards an invisible savior, whom we can only assume is the pregnant person. This free-floating fetus occupies the entire visual field, thus creating the impression that it is a separate and autonomous entity, rather than one that is wholly housed within the womb.

Midway through my shift, a young, Black woman approaches the clinic entrance. As she gets closer, it looks like she might be 20 or in her late teens. She wears a dark hooded sweatshirt and sunglasses. I walk toward her smiling and say, “Are you here for an appointment?” With head bowed she nods a yes. I then say my standard line, “Welcome, please check in with security when you enter.” We cross the line that separates the public sidewalk from the clinic’s private property. Two women protesters race up to the boundary line, their voices a strange mixture of comfort and anger. One pleads, “Honey, don’t go in there. There’s only one choice they give you. We have a clinic where women have real choices.” I grit my teeth at this deception but say nothing. One of the most difficult parts of the job of a clinic escort is not verbally engaging with protesters.

The client turns her back to the woman urging her to seek another option as she rushes to get inside the clinic. I open the door for the client and position my body so as to block out the protesters’ voices the best I can. One of the women outside shouts, “What you do in there you will regret for the rest of your life.” I stand in front of the clinic door, hoping to obstruct the protesters from seeing through its tinted glass, and perhaps muffle their raised voices. What I’m doing might make this one client feel a little more protected from their harassment.

Abortion-rights and anti-abortion supporters stand outside of a Planned Parenthood abortion clinic in New York City.

Andrew Lichtenstein/Corbis/Getty

Clients are subjected to the direct entreaties of sidewalk counselors who claim to be concerned for their well-being. By threatening her with the possibility of a lifetime of guilt, the protesters are acting as if the “abortion-minded” woman needs to be redirected towards motherhood in order to save her from the consequences of what she is about to do. As my co-author Alesha E. Doan and I discuss in our 2019 book, Abortion Regret: The New Attack on Reproductive Freedom, as the anti-abortion movement grew increasingly confrontational and violent, some leaders began to worry that the public had come to see pro-life activists as fanatical “fetus-lovers” who lacked any compassion for women. Seeking to counter this perception, they urged the movement to also focus on the grieving “post-aborted mother” who would inevitably come to regret her rejection of motherhood as the second victim of abortion after the fetus. In so doing, they argued, it could reclaim the moral high ground as the true champions of both. As National Right to Life President at the time, John C. Willke pithily put it, “Why not love them both?”

The sidewalk counselors warn that inside the clinic “there’s only one choice they give you.” This admonition flies directly in the face of the informed consent protocols that reproductive health clinics use to ensure that clients are provided with non-judgmental information about all their pregnancy options so they can make independent and knowledgeable decisions.

Nonetheless, many anti-abortion activists are convinced that true consent is impossible. For example, in 2005, following a public hearing on proposed changes to the state’s informed consent law, lawmakers in South Dakota established a task force to investigate whether women had been misled into having abortions by providers who failed to inform them that “the procedure terminated the life of their existing offspring,” resulting in maternal grief upon realizing they were “implicated in the death of their own child.” Grounded in the legislature’s finding that “as a matter of scientific fact an abortion terminates the life of a whole separate unique being,” it is not surprising that the task force reported that “the procedure is…inherently coercive” because “it is so far outside of the normal conduct of a mother to implicate herself in the killing of her own child.” This view, while clearly incompatible with the concept of informed consent, is consistent with their argument that “abortion is a completely unworkable method for a pregnant mother to waive her fundamental right to a relationship with her child.

When the protester urges the client to go to a “clinic…with real choices,” she is referring to crisis pregnancy centers, which are run by anti-abortion groups. CPCs seek to persuade who they refer to as “abortion-minded” women to choose motherhood so as to avoid the ostensible trauma of abortion regret. As Amy G. Bryant and Jonas Swartz write in the AMA Journal of Medical Ethics, CPCs commonly “strive to appear as sites offering clinic services and unbiased advice” when in actuality most “are not licensed and their staff are not licensed, medical professionals.” Compounding this misdirection, a recent report, “The Alliance: State Advocates for Women’s Rights and Gender Equality,” found that in the nine states studied, “almost two-thirds of the CPCs promoted patently false and/or biased medical claims about pregnancy, abortion, contraception, and reproductive health care providers.”

Indeed, a quick perusal of the websites of the country’s largest umbrella organizations that provide support and resources to local CPCs makes clear that motherhood is the only choice they offer. Care Net’s stated vision, for instance, is a “culture where women and men faced with pregnancy decisions are transformed by the Gospel of Jesus Christ and empowered to choose life for their unborn children.” In a similar vein, the National Institute of Family and Life Advocates (NIFLA) broadcasts that it “exists to protect life-affirming pregnancy centers to empower abortion-vulnerable women and families to choose life for their unborn children.” NIFLA proudly declares, “Together, we can love them both by providing life-affirming options.”

The sidewalk counselors Dawson encountered are often depicted within the anti-abortion movement as being the last best option for changing the hearts and minds of women whom they believe are about to make a terrible mistake. According to the Pro-Life Action League, which was founded in 1980 by Joseph M. Scheidler, a pioneer of the militant direct action mode of protest against abortion providers:

“It is a last attempt to turn their hearts away from abortion and offer real help. Thousands of children are alive today because the Pro-Life Action League was there at the moment of crisis. We care about the women being exploited by the abortion industry as well as the innocent babies being killed. That’s why we’re there on the sidewalk outside abortion facilities.”

In a training video, Ann Schleider, current president of the League, emphasizes that the goal of sidewalk counseling is to prevent women from walking out of the clinic as the “mother of a dead baby.” Schleider stresses that in contrast to other “on-the-street” activists, sidewalk counselors are engaged in a “unique ministry” aimed at offering “compassionate outreach” to women in a time of crisis.

On any weekday the number of clients can vary from four or five over a two-hour shift to more than 20. On Saturdays, the numbers are greater, in part because of work schedules and the availability of supportive friends or partners who might accompany them to the clinic. Clients need to have scheduled an appointment ahead of time and wear a mask to enter the clinic. Once they go through security, they enter a waiting lounge. Each client might be there for a different reason: prenatal counseling, birth control, abortion services, or STD testing and care. While they wait for their appointments, they are shielded from the sounds and drama taking place outside the clinic.

I now see an elderly white man get out of a car and place a poster on a tripod opposite the front of the clinic. In large white letters on a black background, the message reads: “Stop the genocide of black babies.” Below it there is an image of an African American infant. I’ve seen this same poster and others like it on a regular basis. Clearly, it is aimed at Black clients and pedestrians. I never would have guessed that this poster’s charged messaging would be alluded to in a footnote to Justice Alito’s Supreme Court opinion months later.

The “stop the genocide” poster introduces a deeply racialized message into the protest space in front of the clinic. Accusing Black women seeking abortions as being complicit in betraying the interests of their community perpetuates the central message of the anti-abortion movement’s “Black Genocide” billboard campaign. Messages such as “Black Children are an Endangered Species,” and the “Most Dangerous Place for an African-American is in the Womb,” began as a campaign in 2010 with the placement of 65 billboards in mostly Black neighborhoods in and around Atlanta; it soon spread to other regions of the country.

In response to this campaign, the reproductive justice organization SisterSong, which was founded in 1997 in order “to advance the perspectives and needs of women of color,” established Trust Black Women. This partnership of more than 40 Black women-led organizations, has been at the forefront of the fight to shut down this pernicious effort to “relegate black women to breeding machines with no right to make personal choices about family formation.”

As evidenced by the “stop the genocide” poster, the effort to “shame- and-blame Black women who choose abortion” for endangering “the future of our children,” has expanded beyond the billboard campaign into the clinic protest space. The underlying eugenical thinking of this genocidal message has been given credence by Justice Thomas Clarence who claimed in his concurring opinion in Box v. Planned Parenthood of Indiana and Kentucky that abortion is “an act rife with the potential for eugenic manipulation…which can be used to target specific children with unwanted characteristics. Law professor Melissa Murray writes in the Harvard Law Review that Thomas advances “a masculinist vision of abortion” which casts Black women who have abortions as “co-conspirators with eugenicists …in orchestrating the Black community’s destruction.”

Needless to say, this conspiratorial thinking ignores the many reasons, including structural racism, poverty, and lack of access to health care, as to why Black women have a disproportionately high abortion rate.

Pro-life demonstrators attempt to convince a patient surrounded by volunteer clinic escorts not to enter the EMW Women’s Surgical Center, an abortion clinic, on May 8, 2021 in Louisville, Kentucky. Various anti-abortion religious groups and members of pro-life organizations gathered on the sidewalk near the clinic to wish approaching patients a happy Mother’s Day and convince them not to enter.

Jon Cherry/Getty

Most people who walk by the protesters and their posters ignore them. A few shake their heads at the more graphic images that purport to show aborted fetuses. I wonder if I might become numb to these depictions after seeing them week after week. My brooding is interrupted by a young woman who comes up to me and says quietly, “Thank you for your work.” She moves on before I can nod my head in thanks.

I glance at my watch, and only half an hour has passed. So far, there hasn’t been much traffic entering and leaving the clinic, but that can change.

And it does. As the young woman who thanked me walks away, a tall man I hadn’t seen before runs up next to her and shouts, “Don’t thank him. He’s part of the murder factory in there.” He points to the front of the clinic. She scoots away before he can spew more invective. He’s not done though. He turns around toward me and says, “Evil, evil, so much evil.” I feel I am looking into the eyes of a bully, one who could snap at any moment and commit an act of violence. I try to forget the feral look in his eyes as I step back to the clinic entrance.

I don’t have time to process the encounter because the woman who had entered the clinic earlier in my shift was now coming out of the building. I notice she has papers and a brochure in her hand, which likely is information about her next appointment. In a low-key voice, I ask, “If you need any assistance, let me know.” She manages a smile but shakes her head no. At that moment I see the two women who accosted her at the beginning of my shift walk toward the clinic entrance. I brace myself for what will happen next.

A red SUV pulls up to the curb. I assume it’s her ride. The protesters now are a couple of feet away from the clinic’s property line. They are primed and ready for action.

As the client moves away from the clinic entrance, the two women double-team her as she walks toward the car. One says in a sweet and maternal voice, “Dear, let us help you not make the biggest mistake in your life.” The other one chimes in, “We can take you to a clinic free of charge where we have counselors and support for you and the baby growing inside of you.”

Of course, the client might not even be pregnant, or she might have already had an abortion, but that matters little to the protesters. They see a vulnerable, young woman who seems tentative—just the kind of person they go after.

Don’t stop, I say to myself, hoping she can hear my thoughts. Whatever you do, keep moving.

But she does stop. Both women move closer to her. They are just 10 feet from me. I can only see the side of the client’s face, but she appears confused. One of them hands her a rosary, while the other woman says, “We have people who can take care of you in a loving and peaceful setting.” The woman who handed her the rosary follows up: “We can explain all the choices you have in how to take care of your baby without the shame and regret of being forced to end a life.”

The client stands there like a deer caught in the headlights. All three begin to move farther away, and I can no longer make out what is being said. What do I do? We are not supposed to intervene if the client chooses to speak with protesters or if there is no threat of violence or harassment. But in this instance, it’s just not clear if she is frightened and overwhelmed or trying to engage, so I decide to find out if she needs any assistance.

I catch up to the three of them and ask her, “Do you want me to walk you to the car?” My words seem to jar something in her mind, and she nods yes. Together we quickly walk. She gets in the front passenger seat of the car. One of the sidewalk counselors calls after her, “Remember, you can call the number we gave you any time of the day. Any time…” The car takes off before she finishes her sentence.

The other protester turns around and faces me. As she steps closer, I back away to make sure whatever she has to say doesn’t happen inches away from my face. The smiling countenance she wore with the client is gone. Her face is taut, and her voice becomes a snarl. “We have every right to talk with that girl. You can’t prevent us from helping her.”

I say nothing and walk back to the clinic entrance and resume my stance behind the clinic’s property line. I’m not sure if what happened is a small victory or just wishful thinking.

At noon I finish my shift. After I say my goodbyes and thank yous to the security guards I walk back out onto the street. Without my clinic vest, I appear to be just another pedestrian walking home or out to do errands, but I am aware that my right hand is shaking, and my heart seems to have skipped a few beats. This has happened before following a shift. It’s as if my body is reminding me that despite the protesters’ chants of divine love for “unborn life” those words often disguise a rage that might turn on me at any moment. I walk faster, but I know my hand will continue to shake until I get home.

Shortly thereafter, I suspended my clinic duties. A recent uptick in Covid infections and emotional burnout from dealing with protester behavior during the pandemic took a toll. In the meantime, in the wake of the leaked Alito draft opinion, other clinic escorts have told me they have noticed incremental changes in protester behavior. Their numbers have increased on some days, and two veteran women escorts told me that they have been verbally abused by male protesters in ways they never had experienced before. Another colleague told me that protesters appear more emboldened as they stalk the sidewalk in front of the clinic.

I began my clinic escort shifts in 2018 and now have resumed them this June. Have the approaches of the protesters changed? No. They seem to engage in the same range of protester behavior I have witnessed over the years. We escorts are bracing ourselves for what might change in the months to come.