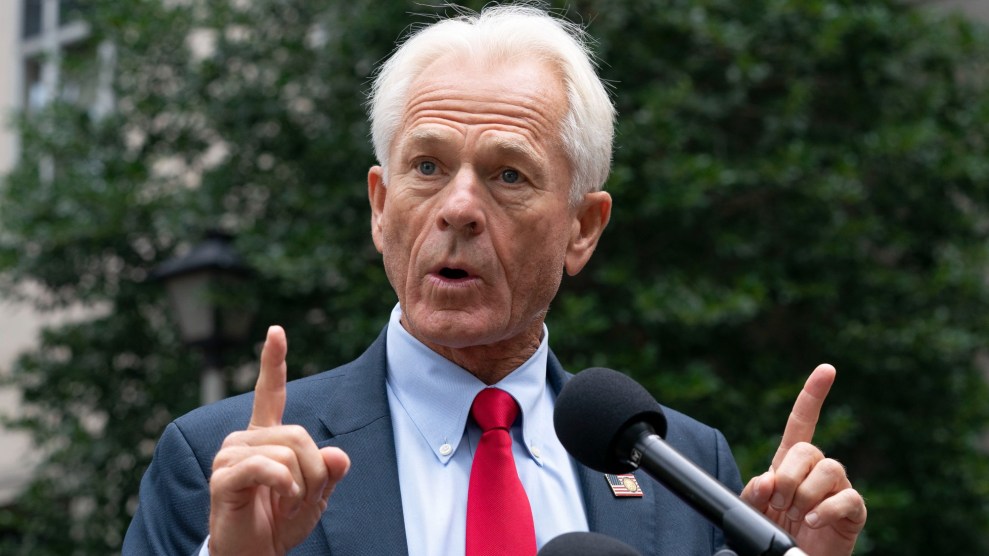

Peter Navarro, who did not testify in his own defense, addressing press, and protestors, outside court on September 5.Jim Lo Scalzo/Zuma

Donald Trump and many of his acolytes take the position that the words “executive privilege” are more or less magic.

Trump, a private citizen, last year tried to assert “executive privilege” to refuse to turn over documents the current executive branch demanded that he return. Trump adviser Steve Bannon argued last year that “executive privilege” allowed him to refuse to comply with a 2021 subpoena from the House’s January 6 Committee, despite the fact that he hadn’t worked in the White House since his 2017 firing.

Former Trump adviser Peter Navarro made a similar assertion last year when he blew off a February 2022 subpoena from the same committee, citing a supposed “executive privilege” assertion by Trump that he did not bother to explain or document.

Executive privilege is a real thing. But that is not how it works. Thus, a DC jury convicted Navarro of two counts of contempt of Congress Thursday following just a few hours of deliberation and trial that lasted barely a day. It follows Bannon’s contempt conviction last year, as well as repeated appeals court rejections of Trump’s post-presidential executive privilege claims and Trump’s indictment for refusing to return classified government documents he secreted out of the White House.

Courts have long recognized that presidents can sometimes assert executive privilege to deny Congress information on confidential advice from executive branch advisers. But the power is limited. Presidents have to actually invoke privilege. Subjects of congressional subpoenas, even if they have a real privilege claim, have to engage with lawmakers and specify what they can and can’t share.

That’s where Navarro screwed up. In an emailed response to a committee lawyer who informed him of a subpoena seeking information related to his actions in the lead up to January 6, Navarro wrote “executive privilege” without explaining further. He later claimed Trump had privately told him to invoke privilege, but he never documented that instruction and didn’t show up for a scheduled deposition or bother to say if he had information the subpoena sought.

Prosecutors argued in court that Navarro’s decision to largely ignore the request broke the law. If he wanted to argue executive privilege, he needed to assert it in response to specific questions and explain if he had documents he was not providing due to privilege.

“The defendant chose allegiance to President Trump over compliance with the subpoena,” Assistant US Attorney Elizabeth Aloi told jurors Thursday. “That is contempt. That is a crime.”

Navarro, unlike Bannon, worked in the White House during the period the committee asked him about. But prosecutors said the actions the panel sought to investigate—Navarro issued a report falsely claiming that voter fraud cost Trump the election and helped devise a plan to use objections to the certification of electoral votes to stop Joe Biden from taking office—were unrelated to his official duties as a trade adviser to the president.

Before the trial, US District Court Judge Amit Mehta barred Navarro from arguing to jurors that Trump had told him to ignore the subpoena. In a pretrial hearing, Mehta called Navarro’s claims of a never-documented conversation with Trump “weak sauce.”

Navarro’s lawyer, Stanley Woodward, scarcely offered a defense during the trial. He called no witnesses. Navarro didn’t testify in his own defense, despite regularly addressing the press outside the courtroom and tweeting through the trial, with frequent fundraising appeals.

Jury in deliberations now. We're in God's hands now. The only thing certain are more legal bills. That's the Democrat's lawfare game.

Will have more once verdict is in. In the meantime,

you can help me fight these weaponized partisan bastards at https://t.co/GRvBWtLTQT https://t.co/uHxYnfWL4A— Peter Navarro (@RealPNavarro) September 7, 2023

Woodard’s main defense was to argue the government had not proven that Navarro’s failure to comply with the subpoena was willful, a necessary component for contempt of Congress, rather than a mistake. Woodward faulted the government’s failure to investigate Navarro’s location on the day of his scheduled deposition, suggesting, without the jury present, that prosecutors had not ruled out the chance Navarro was stuck on DC’s Metro or otherwise detained.

Navarro’s lawyers seemed mostly focused on prevailing on appeal. Navarro has repeatedly suggested that his case will be decided by the Supreme Court. (Bannon’s appeal of his contempt conviction, currently before DC’s Circuit court, will probably provide a preview of Navarro’s chances.)

For now, though, Navarro’s quick conviction offers a lesson on the wisdom of asserting subjective constitutional interpretations in the face of established case law. Navarro faces a maximum of a year in prison on both contempt counts. He is unlikely to get that harsh a sentence, but may well spend months behind bars due to his defiance. Bannon was sentenced to four months, which he will serve if his appeal fails.

Trump and company may feel that “executive privilege” is a powerful incantation that elevates them above the hassles of legal oversight. But so far, at least, the courts disagree.