The view from the floor at W&L’s Warner Center Photo by Tim MurphyFred Thompson is winding his way through his prepared remarks at Washington & Lee University’s Republican Mock Convention, and, as he gestures to the audience once more with his reading glasses, it is clear he has left some children behind. The gymnasium floor at the Warner Center, peppered with big red signs indicating where representatives of each of the 57 states and territories should sit, is about three-quarters full of students in varying states of concentration. The Alaska delegate who was sleeping at the beginning of George Allen’s speech has dozed off again. His friend looks to be asleep too, but then he pulls out his phone and starts texting. A few rows back, another delegate tilts her head back and raises her eyebrows: “Jesus Christ, this is long.”

The view from the floor at W&L’s Warner Center Photo by Tim MurphyFred Thompson is winding his way through his prepared remarks at Washington & Lee University’s Republican Mock Convention, and, as he gestures to the audience once more with his reading glasses, it is clear he has left some children behind. The gymnasium floor at the Warner Center, peppered with big red signs indicating where representatives of each of the 57 states and territories should sit, is about three-quarters full of students in varying states of concentration. The Alaska delegate who was sleeping at the beginning of George Allen’s speech has dozed off again. His friend looks to be asleep too, but then he pulls out his phone and starts texting. A few rows back, another delegate tilts her head back and raises her eyebrows: “Jesus Christ, this is long.”

Since 1908, students at W&L, located about three and a half hours southwest of DC in Lexington, Virginia, have been convening every four years to pick the presidential nominee of one of the two major political parties. They form properly proportioned state delegations, adopt bylaws, and spend the better part of a year studying voting trends and polling data. Before they ever take the stage for the roll call, they’ve spoken with all of the delegations whose nominating contests fall earlier on the calendar, so as to best understand the hypothetical state of play—if Romney’s cleaning up in the early states, the stragglers know better than to go swing en masse for Ron Paul. It’s a political ritual akin to Groundhog Day, if only Punxsutawney Phil wore a blue blazer with boat shoes.

And they’ve gotten pretty good at picking winners: They’re right 76 percent of the time. At one point, South Carolina Rep. Joe Wilson (W&L class of ’69) pops up on the two 20 x 20 video screens to tell us, on behalf of uncommitted Republicans everywhere, “We are looking to the W&L convention to tell us who will be the Republican nominee.”

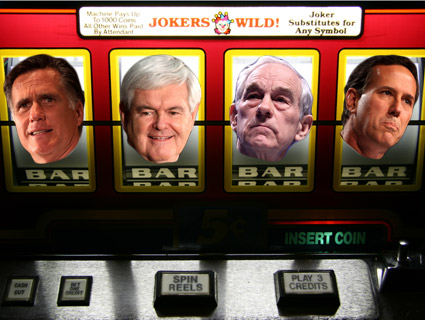

Given the way the race has panned out, that’s not such an unreasonable proposition. Five different GOP candidates have led the national polls at least once—six, if you count Donald Trump. Last week, just when Mitt Romney seemed to have finally taken control of the race with a big win in Nevada, Rick Santorum blew him away in three states. Santorum now holds a commanding lead in Romney’s home state of Michigan. The clusterfudge hasn’t been lost on the convention’s participants. “The Northeast region was joking about how we might go rogue and go Chris Christie,” says Frank Cullo, a senior who chairs the New Hampshire delegation.

Over three days, the student body hears from a series of speakers of various levels of repute before each delegation formally declares a winner (based on their reading of a variety of indicators). Dick Morris spends much of his Saturday morning address laughing over his applause lines with the kind of villainous cackle one normally expects from disgraced former political operatives who have secured lifetime employment with their former opponents. Fred Thompson mumbles his way through an unconvincing endorsement of Gingrich, in which he breaks Effective Surrogate Rules 8–14 by volunteering that his candidate “has more baggage than the airlines.” Haley Barbour hops on stage to the hook from Kanye West’s “Power,” and reflects on how nice it is to be at a school “where they still let ya pray.”

It wouldn’t be a Republican confab without a stealth smear campaign. Photo by Tim MurphyFinally it’s time for the roll call, the centerpiece of the whole event. The state chairs form a long procession up to the microphone, where they briefly introduce their state and announce how they’re voting, depending on whether their state allocates its delegates proportionately or winner-take-all. Texas, which splits its delegates between a caucus and a primary, is represented twice.

It wouldn’t be a Republican confab without a stealth smear campaign. Photo by Tim MurphyFinally it’s time for the roll call, the centerpiece of the whole event. The state chairs form a long procession up to the microphone, where they briefly introduce their state and announce how they’re voting, depending on whether their state allocates its delegates proportionately or winner-take-all. Texas, which splits its delegates between a caucus and a primary, is represented twice.

It’s a mix of earnest trivia, partisan one-liners, and dick jokes. Ohio gave us the Wright Brothers and “unfortunately, the American Federation of Labor. I know, it sucks” (60 votes to Mitt; 3 apiece to Newt and Santorum). Oklahoma announces “zero delegates to the best candidate, Ron Paul!” There are a few scattered boos when Wyoming tells us it was the first state to give women the right to vote. The Maryland delegate is dressed up in a full-body crab suit and informs us that Maryland is “the best place to get crabs” (Romney takes all 37 delegates).

Indiana’s May 8 primary finally puts Romney over the top. When Romney takes the nomination, there’s a loud pop. Red, white, and blue streamers drop from the ceiling, the gym floor explodes with applause, and DJ Khaled’s “All I Do is Win” blares from the speakers. The rest is a formality, but hardly dull: When West Virginia’s state chair, wearing a coal miner’s hard hat with a flashlight on top, recites the normally uncontroversial fact that his state has been around since 1863, he’s heckled by a kid who believes the state should never have broken away (“That’s unconstitutional!”). New Mexico, “home to all kinds of aliens,” gives 18 of 23 delegates to Romney; Guam “home to actual US citizens, unlike our current president,” gives its 9 delegates to Romney.

We wait around for a few more minutes for the man himself to call in and accept the nomination (“Congratulations! Thanks for coming! Boy, this is great; I love gymnasiums!”), but he doesn’t, and things start to get chaotic. The odd “USA!” chant breaks out, as does the compulsory “Ron Paul!” Finally, about 10 minutes later, Romney’s wife, Ann, calls in to graciously accept the nomination and inform us—reading from a script, from the sound of it—that Virginia is “a state with a rich history and one that’ll play an important role in the 2012 election.”

My initial impulse is to second-guess—how could they hand Romney the nomination by such a wide margin, given everything that’s happened in the last week? Why are they so bearish on Santorum? Are we sure Romney’s going to win Michigan? What would happen if Maryland’s actual state party chair showed up in Tampa dressed as a crab? But on second thought, maybe we could learn a thing or two from the whole affair. They’ve crunched the numbers, ignored the day-to-day fluctuations, and attempted to offer something we in the media would rather do without: finality. And why not? It’s been a pretty lousy year for pundits.