Federico Rotman, of the Hubbs-SeaWorld Institute, holds a young California yellowtail at their facility in San Diego. The Institute is helping fund Rose Canyon Fisheries, which hopes to raise yellowtail and other species in a massive offshore farm 4.5 miles off the coast of San Diego. Gregory Bull/AP

If you eat seafood, you’ve likely swallowed some farmed fish: These days, the whale’s share of shrimp, tilapia, mussels, and increasingly salmon sold at American restaurants and seafood counters comes from the hands of aquaculturists rather than local fishermen.

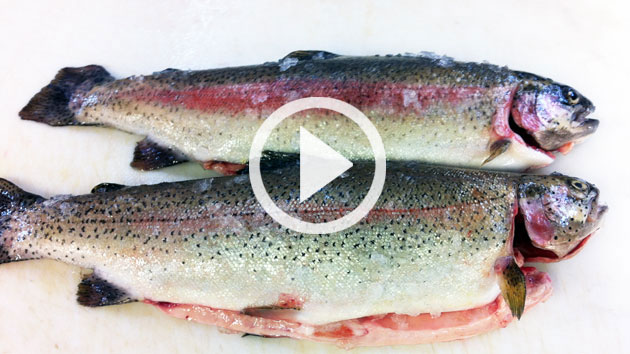

Yet while fish farmers have pretty much mastered the art of raising tilapia in ponds and shellfish next to coastlines, raising marine fin fish—think all the best kinds of sushi, like tuna, yellowtail, kampachi—presents some headaches. The closed saltwater tanks needed to house these species on-land are costly and energy intensive. When they’re raised in nets right by the coasts, waste can build up and damage nearby ecosystems.

That’s why many seafood entrepreneurs are applauding this week’s announcement by the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration: The agency will now allow the large-scale farming of fish in cages deep in the ocean, in waters regulated by the federal government.

The new rule, effective February 12, will allow American seafood farmers to apply for a permit to operate an offshore aquaculture farm in the Gulf of Mexico. According to NOAA, the move will help the US, which raises only 20 percent of its seafood in native waters, catch up with the rest of the world in terms of seafood output. Gulf offshore farms will produce up to 64 million pounds of seafood a year. “Marine aquaculture creates jobs, supports resilient working waterfronts and coastal communities, and provides international trade opportunities,” NOAA stated in a press release.

But not everyone is excited about these future offshore operations.

Gulf fishermen will have to compete with the new offshore ventures, and some worry that creatures that escape from deep underwater cages could breed or mess with their wild stocks. And while the farms will be several miles away from the coastline, some conservationists say that we still don’t know the long term effect such outfits could have on marine ecosystems. According to Politico‘s Morning Agriculture newsletter, several organizations, including the Center for Food Safety and Food and Water Watch, are “analyzing legal options” in regards to the new rule out of concern for the environment.

The announcement paves the way for offshore ventures in other regions of the US to acquire permits. Rose Canyon Fisheries has been waiting since 2014 for approval of its project, which will raise yellowtail jack, white bass, and striped bass in a massive farm miles off the coast of San Diego. Don Kent, head of Hubbs-Seaworld Research Institute, which is co-funding Rose Canyon, envisions the project as a way to correct America’s seafood imbalance—the fact that we import roughly 90 percent of the seafood we consume. “The big advantage we’ll have over those other supplies is the fact that we can grow it locally,” he told KPBS News.

Renowned food journalist Paul Greenberg isn’t convinced these ambitious aquaculture projects will solve America’s seafood dilemma. Americans often eschew native fish species and import exotic varieties instead, he told NPR’s The Salt. “Rather than trying to start up new and complicated ventures, first let’s try to eat the fish we’ve already got.”