Below is our list of creatures and other things that ruined a ruinous year, and the ones that made it just a little more bearable. It is by no means exhaustive. It features a turkey, a cat, two ogres who were dead before 2020 began, some workers who couldn’t bear to work anymore, some journalists who worked overtime, the fucking Senate, eggs, and more.

As coronavirus infection rates are rising and the death toll is climbing to horrific heights every day, millions of people are facing eviction, hunger, poverty, and illness. Meanwhile, Senate Majority Leader Mitch McConnell (R-Ky.) seems completely unbothered by the widespread misery engulfing the country. After agreeing to a COVID relief package in March at the beginning of the public health crisis, which included $1,200 stimulus checks for more than 127 million people, and $600 a week unemployment insurance for the people out of work, nine months into the pandemic, the Republican senator from Kentucky spent months resisting passing any more aid. A few points of contention existed with several items in the various bills—one gnarly issue was that the Dems wanted funds to go to states and cities while the Republicans viewed local aid as bailouts for liberal enclaves—but McConnell and his party’s recalcitrance boiled down to much more than a few dollar signs.

The majority leader had bigger interests to protect: namely making sure that corporations would have liability shields over coronavirus lawsuits. Not only would McConnell’s wealthy friends and funders not face repercussions for failing to keep workers safe, the Senate’s inability to pass a bill meant that the Biden administration would have an even more difficult job in trying to fix the economy. Then, McConnell could argue, since the economy is in such bad shape, the government couldn’t afford to spend money to help the public. Win, win—if you’re a Republican senator.

When another coronavirus aid package finally passed three days before Christmas, it was nine months into the crisis and didn’t even come close to what the public actually needs. And since it’s worth keeping score, six Republican Senators voted against it.

The Republicans’ refusal to act on a meaningful coronavirus relief package is part of their larger pattern of either ignoring or trampling on the common good. Whether it’s trying to dismantle the Affordable Care Act or passing tax cuts that disproportionately favor the wealthy, this year has revealed that not only are their priorities backwards, many of them seem perfectly fine with untold economic ruin, unimaginable human suffering, and the systematic undermining of democratic institutions. And while the GOP certainly doesn’t hold a monopoly on grotesque self-interest—though they seem determined to prove that they’re the best at it—as far as I’m concerned, the US Senate, especially Republicans in the so-called world’s greatest deliberative body, has been unique in displaying monstrous contempt for the common good.

And it’s not just coronavirus relief they made close to impossible. As the Black Lives Matter protest movement, a multiracial and generational demonstration that took root in cities, suburbs, and small towns, exploded earlier this year, some senators concluded that this era was the perfect time to open a new front in the battle against civil rights.

Exhibit A could be Sen. Tom Cotton (R-Ark.), who wrote an incendiary and controversial op-ed for the New York Times entitled “Send In The Troops.” (After criticism from readers and NYT employees, an editors note was attached, the top Opinion’s editor was fired and another one was demoted.) Cotton argued that much like the military needed to force a high school in Little Rock, Arkansas, to integrate its schools, it also needed to quash protest movements. “One thing above all else will restore order to our streets: an overwhelming show of force to disperse, detain and ultimately deter lawbreakers,” Cotton wrote. “But local law enforcement in some cities desperately needs backup, while delusional politicians in other cities refuse to do what’s necessary to uphold the rule of law.”

Of course, in his rush to demand that the American military be deployed on American streets, he failed to mention that the troops were sent to his home state in 1957 because racist whites refused to let Black students inside. The military was sent to protect Black students.

But it was not just protesters demanding rights that drew Cotton’s ire this summer. He was also singularly obsessed with arguing against statehood and representation in Congress for Washington, DC. Cotton once posited that sure, the District may have a bigger population than Wyoming, but Wyoming was a “well-rounded, working-class state.” I’m sorry, could you repeat that Senator? I couldn’t hear you over the sound of your racist bullhorn.

But despite the many controversies surrounding Trump and his administration—when he shut down the federal government over funding for a border wall, his years-long refusal to release his tax returns, or his incessant and incendiary tweets that would have had Republicans calling for Barack Obama’s resignation—the GOP Senators stood beside him, terrified of his sway over the conservative base. Instead of a system of checks and balances, the Senate was there to defend Trump and ignore his misdeeds while working to please corporate interests at the expense of everyone else.

Donald Trump’s absurd, long-shot and yet still terrifying attempt to reverse the outcome of the presidential election might not have gained so much traction without some friends in high places. Before the electoral college vote, the Washington Post only found 27 Republicans in Congress who would acknowledge that Biden had won the election. Sens. Ted Cruz (R-Tex.) and Lindsey Graham (R-S.C.) are the best examples of Republicans whose towers of convictions can be toppled by the gentle winds of political convenience. Remember, they were both once representatives of the NeverTrumpers, and had very good reasons for their positions. Cruz, still upset over Trump’s obscene insults to both his wife and father, pointedly refused to endorse Trump at the Republican National Convention in 2016. And Graham, still smarting from Trump’s publicizing his personal cell phone number, warned that if the GOP nominated Trump, they would get destroyed—and deserve it.

Ah, how times have changed. Over the last four years, both men seem to be fighting over the spout to see who can guzzle more Trump Kool-Aid. (Graham was the source of mockery in 2017 after tweeting about Trump’s spectacular golf game.) After Trump lost the presidential election by more than 6 million votes and 74 electoral college votes, they still couldn’t find their principles. Graham tried to get election officials in Georgia to toss out ballots, and Cruz agreed to help the president argue his baseless case in front of the Supreme Court, should the new conservative majority yield to the president’s demands and grant a hearing. Fortunately, despite Trump’s confidence that appointing three new justices during his term meant they would rollover like the Republican Party, the nine justices declined to hear the suit.

Though I’ve singled out a few individuals, the problem of the Senate won’t be solved by simply voting McConnell, Graham, and Cruz out of office—and people have tried! The entire institution is a dysfunctional mess. Because each state gets two senators regardless of size, and the two major parties have divided themselves along rural and urban lines, Republican Senators often only compete in smaller and less-populated states. As a result, in the incoming Congress (excluding the Georgia runoffs), the Democrats will represent at least 20 million more people than the Republicans. But if Republicans win at least one of the Senate seats in Georgia, they’ll have the ability to obstruct any part of the Biden agenda they don’t like—which is to say, all of it.

It’s been a deeply terrible year. The pandemic, the killings of Black people that sparked racial justice uprisings, climate disasters, and a slow-motion coup attempt—destined to fail, but designed to undermine democracy—have all combined to form sort of a rolling nightmare for the United States. In November, Donald Trump’s loss offered a moment of hope, but now that Biden has secured the electoral college vote and even McConnell managed to acknowledge Biden’s victory a mere five weeks after it happened, the threat of a Republican-led Senate looms large. Any short-term solutions, economic aid, or a competent pandemic response, are likely to be hampered by McConnell’s greed, partisan blindness, and utter disregard for the welfare of the American people. Any long-term solutions, fighting climate change or expanding healthcare access, would be dead-on-arrival. The GOP has already signaled that the party plans to obstruct the Biden administration any chance they get. As bad as 2020 has been, the Republicans in the Senate are poised to make 2021 just as bad—or, hard to imagine but it’s possible, even worse.

Nathalie Baptiste

There was a point for all of us, somewhere near the beginning of the pandemic, where we said to ourselves, oh shit.

One of my first oh-shit moments arrived after reading Ed Yong’s sobering feature, “How the Pandemic Will End,” in the Atlantic in March. The coronavirus, Yong wrote, was “unlikely to disappear entirely,” and he explained that it was possible that “COVID-19 may become like the flu is today—a recurring scourge of winter.”

I repeat: Yong wrote this in March. The day it published, the United States had so far detected around 68,000 cases of COVID-19 and documented less than 1,000 deaths, according to the CDC. In the days ahead of its publication, California became the first state to mandate its citizens stay home; Dr. Anthony Fauci, director of the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases, said that Americans would likely need to socially distance for “at least several weeks”; and President Donald Trump said he wanted to have the country “opened up and just raring to go by Easter.” While the rest of the country simmered in uncertainty, Yong’s piece was a wake-up call. (And let’s not forget, of course, that Yong basically predicted the pandemic—and warned how unprepared we’d be for it—back in 2018 and 2016, respectively.)

I apparently wasn’t alone in my shock about the story’s findings. The piece was shared by the likes of Barack Obama, Rep. Adam Schiff (D-Calif.), and even Catfish star Nev Schulman. While I can’t tell from the outside how many people read Yong’s piece, Atlantic editor-in-chief Jeffrey Goldberg cited Yong’s work, among that of others, in bringing a surge of 36,000 new subscribers in March, along with 87 million unique visitors to their website, Nieman Lab reports. “We have never, in the 163-year history of this magazine, had an audience like we had in March,” Goldberg reportedly wrote in an email to staff.

Over the next nine months, Yong, already one of the country’s best science writers, would emerge as a leading coronavirus communicator, writing about masks, immunology, and the state of COVID research, among other areas. The guy was churning out Atlantic feature stories like they were free samples at Trader Joe’s. (Check out his most recent cover story, “How Science Beat the Virus,” here.) As much of the media clumsily figured out how to responsibly and accurately report on the ever-moving target that is the coronavirus, he delivered sharp and potentially life-saving information and analysis. As an early-career science journalist a few years out of college, I felt like a gnat watching an Olympic gymnast.

Even before this year, I was mildly obsessed with the award-winning writer for his articles on odd-ball topics like milk-producing spiders, toxic hippo poop, the history stored in whale earwax, and the wonders of hagfish slime (!?). The stories were accessible, fresh, and, from what I could tell, founded on a love of science. The pandemic only solidified my admiration for what I’ve at least dubbed in my internal monologue as “Yong-form journalism.”

Let me give you a specific example. This paragraph—about false-positive rates in early antibody testing from his April article “Why the Coronavirus Is So Confusing”—made my little nerd heart flutter:

False positives are a problem, too. Many companies and countries have pinned their hopes on antibody tests, which purportedly show whether someone has been infected by the coronavirus. One such test claims to correctly identify people with those antibodies 93.8 percent of the time. By contrast, it identifies phantom antibodies in 4.4 percent of people who don’t have them. That false-positive rate sounds acceptably low. It’s not. Let’s assume 5 percent of the U.S. has been infected so far. Among 1,000 people, the test would correctly identify antibodies in 47 of the 50 people who had them. But it would also wrongly spot antibodies in 42 of the 950 people without them. The number of true positives and false positives would be almost equal. In this scenario, if you were told you had coronavirus antibodies, your odds of actually having them would be little better than a coin toss.

It’s not especially elegant prose, or deeply investigative, but it’s instructive, clear, digestible. It doesn’t underestimate nor overestimate the intelligence of readers. And it transforms a relatively complex topic into something one might bring up at a dinner party among friends (okay, okay, at least with my friends). And that’s what science writing is all about.

Jackie Flynn Mogensen

When people sheltered in place this spring, coyotes patrolled the streets of San Francisco. A herd of goats reclaimed a town in Wales. Endangered Thai turtles set a 20-year nest-building record. Los Angeles, which invented smog, had three straight weeks of clean air.

Yet in the Morcom Rose Garden in Oakland, California, nature was not healing.

Gerald, a roughly 20-pound wild male turkey missing a tail feather on his left side, had been a longtime fixture of the tranquil, volunteer-tended park, tolerating the joggers, birdwatchers, and picnickers who passed through his home and sometimes fed him snacks. He liked to spend his mornings waiting in a nearby carpool line with commuters.

But 2020 changed us, and it also changed Gerald. This spring, reports of turkey attacks in the rose garden flooded Facebook and Nextdoor. Local news reports told stories of Gerald kicking and pecking visitors, even jumping on their backs and chasing people into trees. One fleeing woman ended up in the hospital. His favorite targets included older people and baby carriages. In late May the city’s parks department took the extraordinary step of closing the garden “to provide some time and space to work to prevent human-wildlife conflicts.”

Human-human conflict followed as neighbors retreated to social media to stake out pro- and anti-turkey stances. Some called for Gerald to be cooked. The parks department got a permit to execute him June 22, then granted clemency when over 10,000 people (myself included) signed a petition to save Gerald from being euthanized.

You see, if Gerald is a monster, we’re his Dr. Frankenstein. Wild turkeys wouldn’t even be in California without us: Humans forced them here from other states to be hunted. Human behavior also could explain Gerald’s transformation. The director of Oakland Animal Services believes that being fed may have caused him to lose his fear of people; locals think the recent influx of visitors to the rose garden agitated him. I would point you to his heroic qualities: Some have posited that Gerald was simply protecting his chicks.

In any case, Gerald, provided the single most entertaining local news cycle of this godforsaken year. Consider his escapades as officials attempted to neutralize him without harming him. According to Oaklandside’s definitive account:

First, they tried to reinstill a sense of fear in Gerald so that he might avoid humans on his own. They hazed him by charging him and opening umbrellas in his face, though they avoided the most extreme idea—throwing rocks at him.

When the hazing didn’t work, California Fish and Wildlife agreed to relocate Gerald. But first, they had to capture him. They initially tried luring him with food in hopes of caging him, but one park visitor continued to feed Gerald on a daily basis, rendering the bait ineffective. They tried tossing loose nets over him, but he ran away. Oakland Animal Services stepped in, laying netting on the ground, hoping to scoop Gerald up in a snare, but he escaped. Benjamin Winkleblack, assistant director of Oakland Animal Services, baited Gerald with robotic turkey calls, several decoy hens, and an umbrella painted with the likeness of a male turkey. All told, the entire staff at Oakland Animal Services, a number of employees from California Fish and Wildlife, and a team of twenty volunteers failed to capture Gerald.

Gerald evaded apprehension until an expert animal trapper, Rebecca Dmytryk, finally ended his reign of terror. One day in mid-October, after staking out the garden, she tried luring him in with blueberries and sunflower seeds, but then her net gun failed. So, thinking fast, Dmytryk hunched over like one of Gerald’s older victims and pretended to be afraid. When the turkey closed in, she grabbed him by his neck.

Gerald was relocated to the nearby hills, but within a week he found his way to a playground. A spokesperson for the California department of fish and wildlife told the Guardian that its “law enforcement officers went and picked him up again and took him to another location.” Stay free, Gerald.

Madison Pauly

Before 2020, here’s how I would’ve described my cat, Smarty Cat: “His paws have never touched pavement.”

And it was true: Despite being a 12-year-old rescue, Smarty Cat embodied all of the privileges of a kept kitty. He’s particular in his tastes: the afternoon sunshine must hit him just right, he will only eat food that’s slathered in gravy, and he screamed bloody murder any time he was moved from the relative stability of his normal routine.

So when I embarked on a cross-country road trip this summer, my biggest concern was how he’d handle it all. Would he meow his way across America? Would he file for emancipation with the powers that be? Would he even survive?

Turns out I have a really chill cat. He spent days upon days cooped up in a car and he mostly slept. He can adapt to whatever circumstances you throw at him, and he’s still not afraid to like nice things. But mostly he kept me sane and for that I am grateful.

And the description still holds: His paws still haven’t touched pavement.

Jamilah King

If you thought your journalism had value beyond entertainment, would you really be making it available to fewer people, unedited, mid-pandemic-depression? And only to people who can pay? Eat shit. Media’s Vizzinis—Greenwald (“unencumbered analysis!”), Squid Matt (“woke left!”), Mild Matt (“fiercely independent!”), penis-size correspondent Andrew Sullivan (if you must), the Singal guy—can’t hurt you by whining about “epistemic closure” from behind the gates of their influencer house. If the plague profiteers score a 10 for evil, these guys barely register. But they set a sad example: If you make it, if you’re really good, you start a hot-take OnlyFans. If I were being gracious, I’d say it raises questions about their values. If I were being blunt, I’d say it yields a pretty depressing answer. What the hell is wrong with you people?

And don’t lecture me about some kind of return to an industry norm. I couldn’t pay when I first got to this media thing, and I couldn’t pay before that. I have been unable to pay since I was this high, and one of the (so many!!!) lessons was to write for Team Can’t Pay only. Because the vast majority of people, certainly the people who most urgently need real news and maybe even decent analysis, can’t pay for your fucking Substack.

Yes, I know print news costs. I also remember reading the New York Times at the library. Sometimes a fellow Can’t Payer beat you to the crossword, but you could still stay informed, and we took advantage of that without fail. There was a principle at work here: Society is better off when media is free and widely accessible. For a time this more or less harmonized with the prevailing business model. Publishers didn’t sweat the low costs of news access because every added reader meant more eyeballs on the Sears ads, where the real money got made. But the old model has cratered, and the commitment to the ideal of widely accessible media is being tested.

There are no perfect answers (absent huge media subsidies), but some are at least better and more public-spirited. A lot of good energy in the industry is going toward creating subscriber-based media cooperatives. At outlets like The Brick House or Defector, gifted journalists are putting it on the line, navigating new routes through a mercenary economy. My outlet keeps my work free and still provides a good union job; I’m lucky, and there should be more. If you have to charge, charge for something with social utility—don’t funnel cash to the comfortable. It is not a coincidence that these co-ops make jobs for people who need them. It’s not a coincidence that they add color to the industry.

The pinnacle of this profession is to create something with others, something egalitarian, in the spirit of communicating valuable shit to the biggest cross-section of people you can. You acknowledge—just by taking part in any shared enterprise—that one of the things your colleagues do is check your bullshit, complement your gaps, and curb your worst tendencies. Your expertise, authority, access, or resources, such as they are, go toward common goals. It rules.

The alternative is called cream-skimming, an expansive term for screwing small fries. For public goods, it’s serving only the profitable users. In bank lending; it’s cashing in on the safest loans (from the best-off borrowers) and leaving everyone else with a worse pool of risk. In media, it’s trashing your colleagues and skipping town because editors are dumb and you’re smart.

If you’re already loaded and your work isn’t worthless, for God’s sake put it where people can read it. At least the clicks these guys got on their lil’ musings helped subsidize some good reporters. If, when we had the chance, this industry had fought for the kind of media subsidies you see in countries that are marginally less of a racket, maybe journalists wouldn’t be as depressingly outnumbered by bullies, grifters, and death merchants.

Through about the mid ’70s, the US looked poised to keep building out its patchwork social democracy. Then Bonzo and the Koch Youth hit the welfare state like a swarm of locusts, and the idea of adding public goods was out of the question. The unregulated globalization they wrought has been a petri dish for public and private scam-artistry; the quantity and variety of investigable bullshit has exploded everywhere. Just not the backing to unearth it.

Meanwhile, these voxholes want you to pay for what? These embarrassments felt censored? Get a real job, you reprobates. [It is not the policy of Mother Jones that anyone should get a real job.—Ed.]

Daniel Moattar

One afternoon, I looked at the room that has served as my office, gym, restaurant, doggy daycare, Zoom background, and home for most of this year and flew into a rage.

My complaints were many. The room was cramped. The room was cluttered. The room was always 15 degrees hotter than the rest of the apartment. The couch—starting to develop a permanent crater from housing my ass in the exact same spot for between 8 and 12 hours a day—hurt my back.

I convinced myself that, despite all the problems, there was a solution. I needed a desk. If I just had a desk—a proper workspace—everything would be a little less terrible. Already unglued from reality, I decided on the worst way to pursue this harmony: I decided to build it myself.

But how? In ancient times, perhaps cave dwellers learned to build fires by watching their cave-neighbors. In the recent past, you could have asked a friend to come over and guide you through home improvement tasks. In a pandemic, there was a single choice. I went to the only good website on the entire godforsaken World Wide Web: wikiHow.

For the uninitiated, wikiHow is a Wikipedia-esque crowdsourced encyclopedia of step-by-step instructions on how to do almost anything. You can learn everything from how to clean dirty ski gloves to how to defend human rights. Among some of the site’s founding principles: knowledge should be widely accessible, users should own the content they produce, and when it comes to content, more is more—there’s no issue too big or too small to justify a wikiHow explainer. As Kaitlyn Tiffany wrote for the Atlantic last year, wikiHow uses “radical collaboration to assemble a model for how to live a life.” She continued:

wikiHow is a website no one thinks about until they need something […] It’s one of very few common resources that have been remixed mostly for fun and almost never for evil, and it may be the largest commercial platform in existence that hasn’t been accused of exploiting its users.

So much of everyday life has moved online since the start of the coronavirus pandemic. And yet the internet seems as dangerous as ever. Every day I log on feels like an exercise in dodging landmines of disinformation and desperately guarding whatever semblance of personal data I have left. But wikiHow is my online safe-harbor. Back in April, it taught me how to make a no-sew face mask out of a bandana when every mask sold online was backordered for weeks. And I’m not alone. According to Elizabeth Douglas, wikiHow’s CEO, the site’s traffic jumped 25 percent early in the pandemic, with hundreds of millions of people like me trying to make sense of their new, locked-down world. Health and wellness articles started trending; the article How to Make Hand Sanitizer has more than 2.1 million views so far; How to Use Hair Clippers, and How to Find Replacements for Toilet Paper were also popular.

Then spring gave way to summer, and staying at home started to wear on us all. We looked for new COVID-approved hobbies. Millions of people have asked How to Fix Dough That Won’t Rise, How to Play Monopoly, and How to Send a Google Hangouts Invite. I learned how to tie dye a sweatsuit (my new work-from-home uniform) and how to save an overwatered plant (through no fault of wikiHow, this one was unsuccessful; RIP rubber tree).

Recently, the site partnered with the United Nations to combat misinformation online, with articles such as How to Find Trusted Advice on COVID-19, and Mental Health America to provide advice and resources for people struggling with stress, depression, and anxiety during the pandemic.

“It’s wikiHow’s mission to help everyone on the planet learn how to do anything, and we’ve always done that with a warmth, gentle humor, and inclusivity not often found on encyclopedic or educational sites,” Douglas told me. She said through months of shutdowns and sheltering in place, the site has tried to answer obvious questions that people would normally ask their family or friends, as well as the not-so-obvious. “[W]e could have never predicted that every household in North America and beyond would need to read an article like ‘How to Freeze Milk‘, but we are there.” (That article in particular has a perfect five-star rating from 100 percent of reviewers.)

wikiHow is the ultimate pandemic hero because it’s utilitarian, earnest (see: How to Support an Autistic Family Member at Christmas), and even willing to laugh at itself (see: How to Appreciate wikiHow). Tens of thousands of Reddit users contribute to r/weirdwikihow and r/wikihowmemes, where they share original and meme-ified versions of wikiHow’s iconic illustrations.

On TikTok, youths reenact the most outlandish wikiHow suggestions as part of the viral #wikichallenge.

@ricekrrt #firstpost #fyp #foryoupage#wikihow #wikichallenge @shammymanny

These days, as my city heads back into lockdown, I’m feeling slightly better prepared for a winter spent inside, alone. I did end up building and staining a hybrid desk-console-table thing—using a drill and sandpaper and polyurethane and, of course, wikiHow. It’s not the cure-all I’d hoped for, but it turned out better than I expected, which is more than I can say about the rest of this year.

Laura Thompson

Quitters, in the United States, don’t get the love they deserve. Stick it out in quiet desperation is the twenty-first century sutra. Quitters have to beat the odds. They face a marketplace that’s no carrot and all stick: constantly hitting new heights of unregulated cruelty, run by giant bad actors who think minimum wage is $7.25 more than you deserve. Whatever finally did it, the story is usually so ugly you wonder how they held out in the first place (bills).

But sometimes your conscience quits before your paycheck hits—without consulting you—and you realize you can’t, literally can’t, put up with the next grope, the next racist taunt, the next little act of cruelty towards colleagues or clients or customers, and you’re out.

This year, we’ve talked to many people who quit their jobs. They, like you, glued themselves together every morning with anxiety over rent, debts, people to feed, and then hauled themselves back into work. And then, one day, they said no. These aren’t always stories that grab headlines. They’re small, intimate tales of capital and life during this pandemic, like a shelf of chipped and colorful mugs.

Happy holidays to the quitters. Read their stories.

Daniel Moattar

Just before the election, Miles Taylor revealed that he’d written the anonymous New York Times op-ed “I Am Part of the Resistance Inside the Trump Administration” while serving as the Department of Homeland Security’s deputy chief of staff. I was curious what kind of person would present himself as a heroic resister after having helped lead a department that separated thousands of families at the border. So I did some Googling and found 2020’s Monster of the Meritocracy.

Taylor’s path to power started in the halls of Congress, where, working as a congressional page as a teenager, he ran into Vice President Dick Cheney and wished him luck in his reelection bid. Taylor wondered in his high school paper why he, a Democrat, would wish a Republican good luck. But in what would become a pattern, he cut himself some slack. While his classmates were worrying about how they looked to that “special someone,” he was worrying about how he looked to the vice president. He styled himself a young insider, having already interviewed Chris Matthews and dined with Sen. Dick Lugar (R-Ind.).

On a break from Indiana University, he interned for the Defense Department and then for Cheney before becoming, at 20, the youngest political appointee in the Bush administration after getting a spot at DHS. As a Marshall Scholar, he split his time between Washington and Oxford while working to open a DC charter school, write a book on “The Rise and Fall of America’s Post-9/11 ‘Freedom Agenda,’” and produce a documentary about congressional pages. After Oxford, he worked on the Republican staff of the House Homeland Security Committee.

Taylor could have left Capitol Hill for any number of lucrative (if mildly monstrous) gigs. Instead, under President Donald Trump, he rejoined DHS, which had just implemented the first Muslim ban. From there, he quickly rose from an adviser position to chief of staff of the 240,000-person department.

Here are a few of the things DHS did as Taylor climbed the ladder there: It implemented a new Muslim ban, which Taylor publicly defended. It moved to strip some 700,000 immigrants who’d come to the country as children of their work permits, and it tried to do the same to hundreds of thousands of people who’d been living with Temporary Protected Status for decades. It announced a wealth test for prospective immigrants. It separated thousands of families at the border and forced asylum seekers to wait in dangerous Mexican border cities, where they were extorted and kidnapped.

What exactly Taylor was doing while all this happened is unclear. In his telling, he resisted. He claimed, for example, that he tried to stop, or at least slow down, the “zero tolerance” policy that split up families at the border. A Trump administration official provided a different perspective to BuzzFeed, saying, “On multiple occasions, I sat within inches of Miles Taylor during meetings solely focused on ‘zero tolerance’ policy, and he was neither silent nor vocally opposed to the weighty decisions before us.” We do know that none of Trump’s assaults on immigrants prompted Taylor to publish his anonymous op-ed; he decided to write it because Trump resisted lowering flags to half-mast after John McCain died.

Taylor faced no immediate consequences for his work at DHS. After he left, Google quickly hired him as its head of national security policy engagement. When some employees later objected, the company misled them by saying Taylor was “not involved in the family separation policy.” As emails obtained by BuzzFeed showed, Taylor provided talking points and a “Protecting Children Narrative” to then-DHS Secretary Kirstjen Nielsen as she claimed that there was no family separation policy.

Along with his Google responsibilities, Taylor found time to write his book, the #1 New York Times bestseller A Warning. In the book, the author, “Anonymous,” writes that family separation was a stain on the country and the leaders of DHS without revealing that he was one of them. Taylor later said he regretted not doing more to stop the policy. But when news broke a few months afterward that more than 500 parents separated from their children still hadn’t been found, Taylor returned to his usual obfuscating, falsely suggesting that it was because a lot of the parents didn’t want to “claim” their kids.

This is the way Miles Taylor talked about family separation LAST WEEK ("It's horrible. But…") when news broke parents of 545 separated kids still cannot be located. He later deleted the tweet. pic.twitter.com/2QW0TpsNVv

— Jacob Soboroff (@jacobsoboroff) October 28, 2020

A week before the election, Taylor revealed he was Anonymous. By December, he was playing the victim. A Washington Post profile reported that he was moving between undisclosed locations after receiving death threats, that his finances were in “tatters” but not in tatters enough to be without private security, and that he’s had “serious marital problems.” Told that he sounded like someone with electoral ambitions, he wouldn’t say whether he was planning to run for office. The meritocracy has more rungs to climb.

Noah Lanard

A few years back, I was at a minor league baseball game in Geneva, Illinois, watching the Kane County Cougars play the mighty Burlington Bees, when a player on the visiting side looked up from his folding chair in the bullpen and asked me how long it would take to get to Chicago from there.

At the time I found it amusing (this kid really called me “sir”). Ever since I’ve found it kind of affecting. At the lowest levels of the minors, a baseball game feels astonishingly intimate. Your grasp of what is happening—stripped of the histories and stakes that shape a big league matchup—feels smaller, but your sense of the people playing it is overloaded. You can sit along the third-base line, feet up on the dividing wall, and hear everything: the ambient noise of warmups; teenagers from Georgia and the Dominican trying out each others’ slang; the exultation and frustration. The veil of mystique that separates performers from fans often slips, if it’s there at all. I’ve seen players carry on conversations for innings at a time with total strangers.

The question about Chicago was the whole minor league experience, in a way. You’re somewhere in the exurbs, trying to make it to the city. Most people never will. I told him it was half an hour by car.

There will be 40 fewer minor leagues farm teams next year than there were in 2019. Those cutbacks hit hardest in the South and Midwest. West Virginia lost all four of its minor-league franchises. The entire Appalachian League got the boot. (It has been reconstituted as a summer league for unpaid college athletes.) The minor leagues—which rely on in-person interactions like concessions and ticket sales—were hit hard when the pandemic forced the cancellation of their 2020 seasons, but that’s not why these franchises got kicked to the curb. Plans to dramatically reduce the number of minor league franchises and players were in the works long before that, because Major League Baseball is filled with insufferable ghouls.

You don’t have to speculate about why big-league clubs decided to reduce their minor-league affiliates by 25 percent. They brag about it. In a 2019 piece at FiveThirtyEight titled “Do We Even Need Minor League Baseball?” baseball insiders argued that the minors were an inefficient way of grooming players to become major leaguers. There were more effective ways to, say, add velocity to a teenager’s fastball or improve a hitter’s launch angle than playing games—this kind of work could be done at closed-door facilities, and any time of year. And there were just so many minor leaguers. Why pay all those prospects, when only 10 percent of them will ever get to Chicago?

It should go without saying that one of the teams driving this movement—though by no means the only one—was the Houston Astros:

[T]he Houston Astros, a model of modern player development, bucked that trend a few years ago. After the 2017 season, they reduced their affiliate count from nine to seven clubs. The Astros believed they could become a more efficient producer of talent with fewer farm clubs.

Of course they did. At the time, the Astros were being feted as baseball’s new meritocrats. Their ex-McKinsey general manager reshaped the organization with a consultant’s eye that allowed them to win by being smarter. Then, just a few weeks after that story ran, we learned that they actually won their World Series with an elaborate (and in retrospect hilarious!) cheating scheme in which team personnel would bang on trash cans to indicate what pitch was coming next. It turns out “rules” are the ultimate inefficiency.

Paying lots of people to play baseball was a problem, in developmental and financial terms, to be solved by paying substantially fewer people to play less baseball, in substantially fewer places. It’s a testament to the almost religious levels of self-absorption among Major League owners and executives that they didn’t think (or perhaps just did not care) about just how awful it sounds to tell people, publicly, that baseball games are a wasteful byproduct of professional baseball, as opposed to the entire point of professional baseball.

Even as other sports produce better highlights or cooler players, baseball’s great asset is that it’s there. A game is a nice place to be, with friends or family, reasonably close to where you live. It’s a beer garden and a playground, a Hinge date, a happy hour, a place to go when you’re on the road and you don’t want to be alone. One turn-of-the-century Masshole called his saloon “Third Base,” because it was the last place you stop on your way home. The jargon’s changed but the spirit’s the same: It’s a kind of Third Place. Most people who go to these games will not particularly care if a pitcher throws 90 miles per hour instead of 93. They might not even be able to tell you what happened on the field at all. Getting rid of the ubiquity that’s sustained its popularity for 150 years gets sold as streamlining. It’s really just strip-mining.

I mourn the overhaul from the comfort of a city that still has three professional baseball teams. But, still, it hit us. In November, the New York Yankees cut ties with their Staten Island affiliate, as part of this huge and historic contraction in minor league baseball. Richmond Bank Ballpark on Staten Island, one of the best places to watch a baseball game in the United States, won’t have a team anymore.

This is a tragedy. The park is a five-minute walk from the ferry, and right on the water. If you sit in the right spot, you have a spectacular view of Lower Manhattan. Huge ocean-going ships pass just beyond the right field fence. The Staten Island Yankees of the short-season class-A New York–Penn League have played there since 1999. It is entry-level baseball; the players are talented but raw. The last time I was there I witnessed a game-winning pickle.

I find this crushing, as a baseball fan, but it’s not just a baseball story. By this point in the 21st century, you should know enough to run full speed away from people who talk about optimization—people who take over beloved institutions with little appreciation for what those institutions actually do, who talk about getting better by getting leaner, about rooting out inefficiencies and pivoting into a new “space.” These people buy newspapers and gut them. They buy your company and make you build a stage for the announcement where they lay you off. They take over the post office and, well, you know. As the pandemic blew up the global economy, those trends were only exacerbated. Governments might let crises go to waste but big businesses don’t. They use these moments to accelerate consolidation and remake industries. Most of America’s largest companies laid off employees during the pandemic even as they turned a profit.

What little leverage minor league franchises might have had disappeared with their 2020 seasons, although some, like the Staten Island Yankees, are pursuing their options in court. This month, after the realignment became official, the league offered a tepid helping hand to the franchises it had consigned to the scrap heap. Some of them will be absorbed into MLB-sanctioned summer leagues for college baseball players or “draft leagues” for players looking to showcase their wares for scouts—which is to say, they will be replacing rosters of low-paid workers with unpaid amateur volunteers. Others are abandoning the farm system entirely to try their luck in the independent leagues. Nearly two dozen franchises are still figuring out what, if anything, they’ll do next.

For years, baseball sold you a dream. In 2020, it snapped its fingers.

Tim Murphy

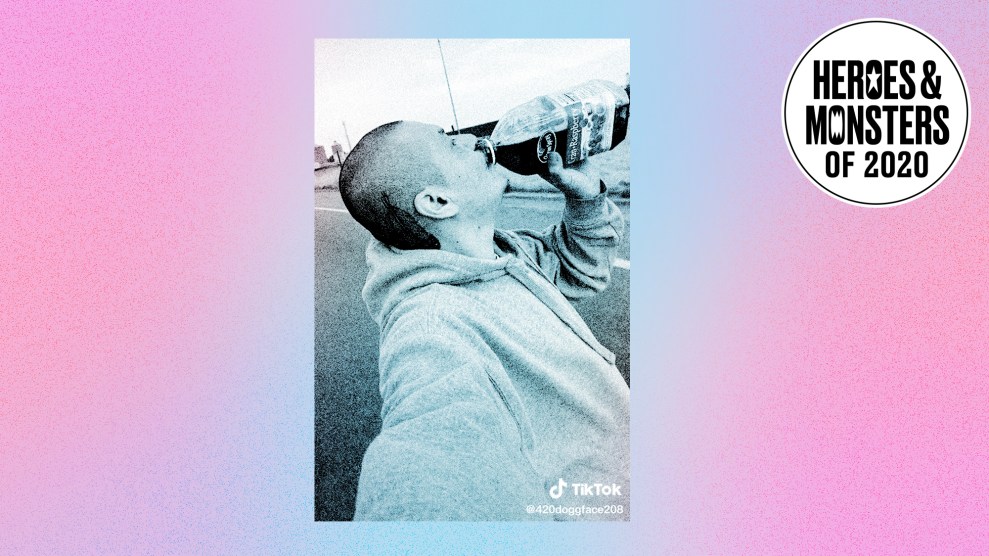

Like many of you, I was inside a home I’d spent far too much time in when I first saw Nathan Apodaca rolling into the pantheon of good vibes. Being too old in spirit, but apparently not in age, for TikTok, I assumed he was an outsider who’d hit on something genius, not DoggFace, the Idaho man who’d been dancing and lip syncing for years.

A year before, the Latinx culture site ReMezcla had dubbed Apodaca, whose mom is Northern Arapaho and whose dad is of Mexican descent, Tío TikTok for his renditions of old hits on a platform dominated by teens. He’d been on Instagram since 2016, where he started out posting photos of his daughters playing with his dog or practicing viola. When they weren’t around, the posts—a photo of edibles for a 2 Chainz concert in Denver, for example, using the hashtag #420Souljahz—skewed stoner dad.

After his daughters introduced him to TikTok, he found his niche with videos that used the potato warehouse he’d worked in for nearly two decades as a stage. His general philosophy comes through in a post of him putting together cardboard bulk bins to System of a Down with the caption “work sucks sometimes but o well SMILE.” He hit 1 million views with a post that was just him dancing to Doja Cat.

Apodaca was only skating down the road in September because he kept a longboard in the back of his Dodge Durango. It had more than 330,000 miles on it, and he knew to expect mechanical difficulties. So when the battery went out on his way to work, he started skating, the New York Times explained.

Since he posted the video of his improvised commute, his life has entered the realm of fantasy. Ocean Spray and an Idaho car dealership gave him a cranberry-red pickup with a juice-filled bed. He moved from an RV without running water to a five-bedroom, two-story house. The experience of having one floor for sleeping and another for living has been a revelation. As he told People, “We have a whole house underneath us.” On a trip to Las Vegas, he proposed to his girlfriend, Estela Chavez, whom he met at the potato warehouse, by trying to sing Adam Sandler’s “I Wanna Grow Old With You” in her native Spanish. (She said yes.) During a visit to a Beverly Hills cosmetic dentist, he got veneers.

The subtext is that Apodaca wound up with running water, space for his daughters to visit him, and a truck he can count on because he managed to maintain immaculate vibes without those things, not because he was doing a job we’ve been at pains to praise as essential. And since this is 2020, the latest news is that Apodaca and Chavez have tested positive for COVID-19. He’s still dancing. Now to “I Will Survive.”

Noah Lanard

Presumably, some political appointees who served in the Trump administration did so with earnest intentions, hoping to bring dignity and professionalism to the task of advancing the Republican agenda of deregulation, austerity (for non-cronies), and upward wealth redistribution. Then there were the full-on MAGA-bots like Sonny Perdue, the Georgia politician and agribusiness entrepreneur who became agriculture secretary. He spent his 2020 like he spent the other years of his Washington stint: flattering his boss at every opportunity, and lavishing largesse on political allies while undercutting poor people and food-system workers.

Perdue is a kind of an easy-going Southern version of the president he served so zealously. Like Trump, he’s a former Democrat who ascended to political power (in Perdue’s case, Georgia governor) in a stunning upset. As governor from 2003 until 2011, he celebrated the state’s legacy of chattel slavery—signing 2009 legislation making April “Confederate History and Heritage Month,” honoring the “more than 90,000 brave men and women who served the Confederate States of America.” He was an early adopter of race-motivated voter suppression, signing into law one of the nation’s first “strict” ID laws.

Purdue merged the voter-fraud myth with another racist fantasy, also fervently indulged by Trump, that undocumented immigrants burden taxpayers by siphoning welfare benefits. “It is simply unacceptable for people to sneak into this country illegally on Thursday, obtain a government-issued ID on Friday, head for the welfare office on Monday, and cast a vote on Tuesday,” he declared, backing up his rancid lies with a crackdown on undocumented people. His anti-immigrant machinations worked all too well, creating a crippling labor shortage for Georgia’s immigrant-dependent farms and poultry slaughterhouses.

As governor, Perdue mastered the Trumpian strategy of using know-nothing bigotry as a beard for brazen self-dealing, sometimes involving his own family. In 2005, Georgia state Rep. Larry O’Neal—Perdue’s personal lawyer—managed to pass what the Atlanta Journal-Constitution called a “seemingly mundane tax bill” that included a “a last-minute change” that saved the governor an estimated $100,000 in state taxes.

In 2010, at the tail end of his second term as governor, Perdue named his cousin, David Perdue—who had just stepped down as chief executive of Dollar General discount stores—to the board of the Georgia Ports Authority. According to the Atlanta Journal-Constitution, it was a plum post for the political novice, which he used as a springboard that helped propel him to a US Senate seat in 2014. In this 2017 post, I recount some of the port-related shenanigans the cousins Perdue got up to together, including launching a port-reliant export business. (David Perdue is now locked in a tight runoff election that could decide which party controls the Senate in the next Congress.)

Meanwhile, in 2020, the pandemic ravaged meatpacking workers and put millions out of work, causing a surge in the need for food assistance—both very much areas of concern for the agriculture department. @SecretarySonny (to use his folksy Twitter handle) stayed the course that characterized his entire time at UDSA. The COVID-19 crisis served as yet another opportunity to promote the political fortunes of his boss, without impeding his pursuit of a pro-agribusiness, anti-worker agenda. In July, with the economic fallout from the pandemic generating a massive hunger crisis, Perdue alighted on North Carolina, a key swing state, to stage a rally promoting congressionally mandated food aid as an example of the personal benevolence of Donald Trump. The harangue, which ended with the ag secretary leading a chant of “four more years,” earned Perdue a knuckle-rap from the Office of Special Counsel for violating the Hatch Act, which forbids government employees from campaigning while on the job. The Perdue USDA also insisted that federally funded grocery boxes distributed by food banks contain a letter signed by Trump, touting the administration’s coronavirus response.

While Perdue puffed up the generosity of his boss, the USDA was busy botching the food-relief effort, awarding fat contracts to distributors ill-equipped to handle them, with the result that “some parts of the country got a lot of food, while others got very little,” NPR reported.

Undeterred by the pandemic-led spike in hunger, Perdue also doubled- and tripled-down on a long-held goal: boosting work requirements for the Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program that would eliminate food aid for at least 1.2 million people—about a third of them households containing senior citizens, nearly a quarter with children, and 11 percent with a disabled person, according to nonpartisan think tank Mathematica.

Not satisfied with fighting to take food off the tables of poor families, Perdue also set his sights on farm workers. At the beginning of 2020, Perdue yearned publicly for a way to cut federally mandated wages for migrant farm workers on guest visas. Then the pandemic hit, ripping through migrant farm worker communities, who toiled on with little in the way of protective gear or opportunities for social distancing. Perdue’s response? He continued his effort to cut their wages, ultimately teaming with the Department of Labor on a rule change that will result in an aggregate wage cut worth at least $170.68 million annually over the next ten years—a transfer of money from low-wage workers to relatively wealthy farm owners.

Similarly, while the pandemic savaged meatpacking workers, killing at least 563 as of mid-December, the ag department kept on with a trend it had started in 2019: allowing giant poultry companies to speed up their slaughterhouse kill lines. Faster kill lines boost packer profits even as they put already pandemic-stressed workers under greater strain, while also making proper social distancing even more difficult. An investigation by the Food and Environment Reporting Network’s Leah Douglas found that at least 40 percent of chicken plants operating at the higher speeds experienced COVID outbreaks, versus 14 percent for the overall meat sector. Coronavirus-riddled slaughterhouses, in turn, emerged as primary vectors for spreading the pathogen to surrounding communities.

The Perdue USDA’s largesse to large-scale farmers and agribusinesses went beyond cutting wages and protective measures for their workers. In July, as the general election heated up, the department tapped a Depression-era funding mechanism called the Commodity Credit Corporation to come up with $14 billion—without having to consult Congress—to hand to producers of commodities like corn, soybeans and wheat, ostensibly for losses due to the coronavirus. Using the CCC to hand billions to big farmers—major Trump supporters in 2016— is a signature move of Perdue’s USDA. Citing export losses from Trump’s trade war with China, the USDA lavished mainly huge soybean, hog, and cotton farmers with $28 billion in 2018 and 2019—more than double the price tag of President Barack Obama’s 2009 auto bailout.

Through it all, Perdue maintained his extraordinary podcast, The Sonnyside of the Farm, a monthly testament to the genius of his boss and the glory of big agribusiness. Launched in October 2019, a week after the House of Representatives announced an impeachment inquiry against Trump, the show began with an appearance from Sarah Huckabee Sanders. Entitled “President Trump’s Affection for American Farmers,” the episode featured the host and former White House press secretary competing to see who could lavish the most praise on Trump. Sanders: “one of the the most fun, engaging, charming, and charismatic people I’ve ever been around.” Perdue: “he has an amazing instinctive ability to make decisions.”

In the podcast’s final episode before the election, released Oct. 29, Perdue hosted another MAGA loyalist, the high-living former Wall Street man and TV personality Larry Kudlow, the non-economist who Trump improbably chose to lead the National Economic Council. Kudlow used the opportunity to fluff Trump’s economic record. He praised the tax cuts and the program of deregulation, which, he claimed, “benefitted the people who needed it most,” those “in the middle, and the lower rungs.” It’s little wonder that Trump would train his benevolence on the little people, because “he’s a blue-collar guy” who “worked for years in the construction yards, with all kinds of folks, all colors,” Kudlow informed Perdue’s listeners.

Enlivened by these bald lies, and perhaps feeling a competitive spark, Perdue replied that Trump is “the embodiment of the amazing spirit that built this country.” He sounded quite satisfied after a year spent campaigning for his boss while inflicting lasting damage to poor people and food-system workers during a deadly pandemic that the administration did so very little to control.

Tom Philpott

Earlier this month while washing dishes, my dad jokingly asked my mom, “Can you talk right now or are you doing ‘hot girl shit?'”

My sister and I looked at each other in shock. My dad, a bit clumsily, was remixing a popular TikTok. This genre of TikTok usually depicts someone pretending to cut a phone call short in order to do “hot girl shit.” This can mean anything from applying glamorous, Euphoria-style make up to playing Minecraft. Either way, Megan Thee Stallion’s “Girls in the Hood” blasts in the background.

@wehatelissa

It was hilarious and weird to hear these words come out of my father’s mouth because it signaled to me just how much TikTok had influenced the way we communicate. Admittedly, we had spent the past day repeating the phrase. Even so, the standard of what’s meme-able, and how the app has shifted perceptions of reality during the pandemic, has been bracing.

As of April, the Chinese-owned app had over 315 million downloads in the first quarter of 2020 according to market analytics firm, Sensor Tower. When TikTok launched in 2018, not long after absorbing its predecessor Musical.ly, it filled a crucial gap in the world of short form video. This was only two years after Twitter bought and killed Vine in 2016 (RIP to a real one).

TikTok snuck into every facet of life, seeping onto other social media platforms like Instagram and Twitter, birthing new celebrities, music, and lingo. Briefly, it became the subject of debate around national security. This year, TikTok became our way of curating and articulating our pandemic lives in short phrases and gestures—of making each moment of life memeable—even when we didn’t hit record.

This has allowed TikTok to offer an unending window into niche pockets of the world beyond our own as we quarantine. The app transports you from planttok to skatertok to lesbian TikTok, and to even more unexpected windows like cartel TikTok and prison TikTok. Everyone from Jason Derulo to the Washington Post to Kellyanne Conway’s daughter, Claudia is on the app. TikTok helped pass the time: it forged online communities, cultivated the next generation of cinematographers, and provided an outlet for many Zoomers to process the turbulence of 2020.

But what’s monstrous about TikTok—a massive and unwieldy piece of artificial intelligence—is how much it allows users to dominate those spaces once they’ve found them. Many of TikTok’s most popular sounds and dance trends are created by Black people. And then appropriated widely. TikTok owes its growth, in part, to digital blackface, and how profits and virality garnered from the app more often fall into the hands of wealthy white teens. Digital blackface—wherein non-Black users use Black slang, affect, and body language to essentially put on a virtual minstrel show—is not unique to TikTok. Its roots run deep into every facet of the internet from memes, to GIFs, to the catchphrases and sounds used on TikTok many of which feature images or audio by Black people. It goes back to Elvis Presley.

On TikTok, non-Black creators mimic Blackness by lipsyncing audio or writing comments ripped from Black reality television, Black YouTubers, and ordinary Black people in the media. Minstrelsy is rewarded by ascending these videos to viral heights while the voices of Black creators and the complexity of Black experiences—beyond racist troupes—are eclipsed.

Black creators like @demimykal have tried to draw attention to how younger TikTokers have “literally colonized and white washed almost every Black cultural trend” online. Yet there are no signs that online minstrelsy is slowing down. Besides, what would American internet culture even look like without it?

Just four days before George Floyd was killed by police officers in Minneapolis, Black creators on TikTok staged a “black out” to raise awareness about how Black people were treated on the app and urged users to change their profile pictures to a black fist and follow other Black TikTokers. Two weeks later, the company released a statement apologizing for the unfair treatment of Black creators and announced plans to build a creator diversity collective.

Today, TikTok continues to express its commitment to combating racist algorithms and elevating Black voices. But digital blackface is a widespread epidemic.

On the best days, TikTok is a beautiful crisis of infinite worlds—too many rabbit holes to fall down and a welcome respite from these uncertain times. On its worst, it sheds light on America’s obsession with clout and money, and appropriating not only Blackness, but many communities of color, without giving credit where credit is due.

I am uncertain about the future of TikTok, how the app will evolve or continue to befuddle governments around the world, how it will dictate our vernaculars, our dance moves and the music that plays on the radio. I just hope that in the year to come we can appreciate viral videos for their singularity, their glimpse into the random messiness of life captured online not at the expense of people of color.

Lil Kalish

The protagonist of The Queen’s Gambit, the Netflix show about a child chess prodigy who ascends to the game’s greatest heights, is Beth Harmon. Harmon is what we might call a “cool girl.” She likes beer. She likes chess (technically a sport). She is “chill.” She, almost exclusively, rolls with the boys. And she is just as good as or better than the boys at all of the things they like: chess, drinking beers, and getting girls.

None of this is unrealistic. And (minus her beer skill being born of her alcoholism) they’re all to varying degrees good or neutral. But, in context, it’s kind of weird. Despite the sexism we know was rampant at the time in chess—and still is—everyone seems to love Harmon.

The men she faces off against might sometimes seem skeptical and dismissive of an unknown woman having the gall to challenge them at chess. But after Harmon crushes them, they are gracious. They vigorously shake her hand and wish her the best. Men often don’t treat even each other, let alone women, like this. They lose poorly.

In this way, The Queen’s Gambit can play as a lovable fantasy. As Carina Chocano wrote in the New York Times Magazine, traditionally in “literature and film, the male genius is lionized” while “the female genius is institutionalized.” In real life, Harmon could not rise as easily as she does. That she does, can “cheer us up.”

But there’s something irksome about the fact that even a fantasy like The Queen’s Gambit can only go so far. Beth’s success is individual. This is in contrast to those around her, instead of normal. Almost all of the women in the show who are not Beth are cruel or dumb or cruel and dumb. In the universe of The Queen’s Gambit, the only way to be a woman worthy of anyone’s time is to be an extremely good chess player, or for a fleeting moment, a mordantly witty Parisian model. The other exception to this sits squarely in another tired trope: the sassy Black best friend, who exists mainly to help Harmon finesse her way through tricky moments in the plot.

The cardboard quality of side characters gets covered up by stylishness. The show coasts off its solidly fine, but not great, plot by infusing it with beautiful shots, coloring, and all of the other lavish trappings of prestige TV. These ornaments can try to turn otherwise mediocre shows into the high-brow, but it never quite works. “Everything is brooding, tortured anti-heroes,” Matt Christman writes in an essay describing the frequent emptiness of these pieces of art for Current Affairs, “[with] ironically counterposed musical choices.”

In The Queen’s Gambit’s case, prestige TV tics can’t cover up a reductive arc. Harmon is basically the same person she was as a child: observant, quiet, opaque, and chill. She seemingly reins in her struggles with substance abuse but doesn’t change in any other discernible way from her prior days of drinking and taking tranquilizers.

From her first chess tournament to her big showdown in Moscow, instead, she remains one of the guys.

In The New Yorker, Sarah Miller points out that the central tension driving Harmon in the novel version of The Queen’s Gambit has been nearly stripped from the show. In the book, Harmon requires chess to realize she has worth. In the Netflix version, Harmon’s arc is already completed once you meet her. She “doesn’t need chess to survive,” Miller writes. “She’s a confident girl who finds everyone annoying and wears great clothes and flies off to beautiful places to be weird around guys….If she didn’t play chess, it would be ‘Emily in Paris.'” When a writer at Life asks Harmon about the difficulties of being a woman in a male-dominated sport she says there is none.

There is something alluring about creating a fictional world in which the lived struggles of women, people of color, and LGBTQ people don’t exist. But the line between that and creating an elaborate way of saying they actually don’t exist can be fine. It feels like The Queen’s Gambit walks back and forth across it. Maybe more prevalent sexism exists in the fictional world of The Queen’s Gambit. But we don’t see it. If it is a problem, it’s something to worry about elsewhere, among a few bad apples, not an embedded part of the cultural pathology. That pathology somehow is broken by female success, like magic. As Chocano writes, it’s a fun escape. But it is also a decidedly male fantasy of genius—genius honed in isolation, tortured, full of forgivably toxic byproducts, aloof from society, worshiped rather than nurtured and enabled by others.

This version of genius feels like a disservice to what many oppressed groups must do instead: work together. In the show, this is given too little attention. When Harmon has her first period during her tournament, she is saved by the only other female player there who has a spare tampon. It seems like a certain friendship is about to play out. However, that camaraderie never comes to fruition. The character isn’t heard from until almost the end of the series when she tells Harmon that her success is inspiring for women. By that time, Harmon has literally forgotten who she is.

Ali Breland

“Sunlight is the best disinfectant.” As an allegorical aphorism, it is almost never true.

Enabled by social media, conspiracists, white supremacists, and general hoax types have garnered more exposure—more “sunlight”—and their hate and ignorance has only gone viral and grown. What has slowed down toxic provocateurs like Alex Jones, Milo Yiannopoulos, Baked Alaska, and many others has been their removal from social media. That is a better disinfectant.

It turns out giving hateful rhetoric airtime and a platform doesn’t repulse everyone. In many, cases it actually appeals to them. At scale, sunlight isn’t very helpful. But when administered by consummate deadpanner and budding gonzo journalist Andrew Callaghan, it’s not only effective—it’s very entertaining.

Callaghan created All Gas No Brakes, his YouTube channel, in 2019. Since then he’s been crossing the country in an RV stuffed with friends, documenting the outermost threads that make up America’s extensive tapestry of subcultures. In the past year or so, they’ve made it to FurFest, the Adult Video News Awards, and Talladega Superspeedway. As coronavirus ravaged the U.S. he didn’t slow down, throwing on a mask to get uncomfortably close to the bizarre underbelly of Americana.

Most of Callaghan’s videos are great. But his most important work has come from his forays into the far-right, where he’s just turned the camera on and mostly let them speak.

“I understand sometimes when the left is like ‘Ah well, [the Proud Boys] are violent!’ It’s ‘cause we make self-defense look like assault,” a shrugging Proud Boy leader, Enrique Tarrio, told Callaghan at a summer rally for the group, a neo-fascist organization that describes itself as “western chauvinist.” Its often violent members have managed to dodge the brutal tendencies of police, sometimes even getting chummy with them—something critics suspect is because the groups share discreet relationships, which reporting shows is at least sometimes true.

A few minutes later Callaghan bluntly asked Tarrio: “Do Proud Boys communicate with the police?”

“We do,” he admitted.

Some of Callaghan’s interview subjects that day similarly incriminated themselves explicitly—and, implicitly, the rest of the Proud Boys, by making it clear that there are some absolute dangerous weirdos in the group.

He lets a man dressed only in what looks like a black morph suit—except for his hunting-camo hat and wraparound sunglasses—make himself look even more and more buffoonish the longer the tape rolls, as he confidently prattles off the obscure conspiracy theories he believes. Another guy wearing a softball helmet and ski goggles while holding a massive Trump flag muses that Black Lives Matter maybe isn’t so bad, before he decides to cut the interview short after realizing what he just said out loud.

Callaghan then turns to a guy nearby who has an unspecified vendetta, as evinced by a sign he was holding, against George Soros. One can guess why, given the anti-Semitic roots of far-right attacks targeting the liberal philanthropist.

This is generally how Callaghan’s interviews go. Aside from some cuts to move things along and making Vic Berger-styled surrealist and goofy edits to underscore the absurdity of his subjects, Callaghan mostly just lets them hang themselves with their own rope. And, every time, they do. In almost every video, his patient but general questioning about why they believe what they do consistently reveals anti-Semitic thinking. These are the people he always finds, uncoincidentally, hanging around Proud Boys rallies, Flat Earth events, anti-coronavirus lockdown protests, and the like.

It’s really effective. The far-right groups of 2020, wittingly or not, are antecedents of the far-right internet culture of the mid-2010’s. Their vocabulary of terms—cuck, beta, redpill—came out of 4chan and Gamergate adjacent and affiliated Reddit communities. These were spaces where cruelty was disguised as irony. Being racist was a joke, a troll for the lulz. So ironically throwing up the white power sign to troll the libs in public, while privately identifying as a white supremacist segregationist, is just a slightly less online version of what 4chan trolls were doing in 2014. Callaghan meets them on their own terms. They make jokes to disguise their racism. Callaghan makes journalism that elucidates their racism, disguised as a joke.

Inevitably, journalists reporting on and outlets and publications running straight news stories about the far-right will always register, in some minds, on a frequency aside from irony or disgust. This often well-intentioned coverage will nonetheless prove attractive to swathes of the country, especially the irony-poisoned internet youth who Proud Boys and the like try so hard to convert. While sternly condemning neo-fascists in a crisp, expensive suit and ironed tie is something fancy people who wear fancy suit and ties should definitely keep doing, a self-serious broadcaster raising an eyebrow and saying that the alt-right is “racist” in a slightly raised baritone is never going to resonate with the extremely online. But with his rumpled clothes and flat affect, All Gas No Brakes has figured out how to out-irony the edgelords.

Callaghan himself isn’t just in it for the bit. His lampoons are laced with empathy for some of the subjects he’s critical of. In an interview with Twitch political personality Hasan Piker, Callaghan lamented how often anti-Jewish bigotry came up in his filming. “It’s unfortunate, because these are very curious, investigative people, who are willing to put in tons of independent research time—which most people aren’t down to do,” he explained, bemoaning that their interests and conspiracy thinking always “go back to the Jews every time.”

Given he’s handling such dark currents, Callaghan isn’t blithe about the limits of letting people speak completely freely in videos that will reach a big audience. (All Gas No Brakes videos have been watched 61 million times on YouTube alone, where the channel has 1.5 million subscribers.) He told Vice in an April interview that despite disseminating hours of candid conservations with some of the most unsavory people he can find, he’s still holding on to footage that he has ”refused to broadcast because doing so would directly give a platform to hate speech.” He told the news site that he once cut an interview short because an interviewee at a Flat Earth conference alluded to denying the holocaust.

In his video documenting the Proud Boys rally, Callaghan made sure to include clips from the event showing a student journalist who was shoved to the ground and kicked in the head by a Proud Boy, and of another who accused an independent journalist of bias since she was “Arab.” In highlighting moments like these, Callaghan’s All Gas No Brakes shows what it actually takes to make sunlight work as a disinfectant. In a year where hate, violence, and those who push them have been an ever-present specter, that makes him a hero.

Ali Breland

Roughly three months into a life concealed indoors, a surprise game show appeared on Netflix’s “Top 10” list.

That show, Floor Is Lava, is billed as such: “Teams compete to navigate rooms flooded with lava by leaping from chairs, hanging from curtains, and swinging from chandeliers. Yes, really.”

Had I read the description in another era, my husband and I likely would have skipped. But this was June and our pandemic diet demanded the dumbest forms of everything. What could be dumber then, and therefore more essential for the moment, than cheering on adults traversing across low-budget sets plastered with absurd graphics to compete in a goofy obstacle course for a cash reward of $10,000? Not much!

It’s far from the best show I watched in 2020; that honor probably belongs to I May Destroy You. It definitely wasn’t the worst; Queen’s Gambit, what a corny disappointment! But years later, send me a screenshot from any Floor Is Lava episode, and I’ll be sure to recall how much wine I overdrank that night and why the dumb came as such a balm against the cascade of despair and horror emanating from outside. I’ll also probably torture you with (very false) claims that I could perform better than the contestants we saw in June.

“Want proof?” I’ll ask. Naturally, you won’t. But I’ll ignore that, whip out this photo from then, back when my husband and I filled evenings taking to our own furniture to try the lava on for size.

Inae Oh

On October 5, President Donald Trump lumbered out of the doors of Walter Reed Medical Center, three days after he’d been checked in with a case of COVID-19. He stopped, raised his right hand in a fist and shook it a few times in a motion that combined a pumped-up “rock on” and a jerking-off “whatever.” The gesture instantly conveyed that humility would not be a lasting effect of Trump’s run-in with the disease that he’d downplayed even as it had killed more than 200,000 Americans to date. He was still winning.

The Trump fist pump is the visual punctuation mark of his presidency, dropped during arrivals and departures, at the kickoff of a speech or in the afterglow of a rally, even in a Christmas message. In the moment, it can come off as a cheesy throwaway move. It often makes Trump look like a duck-faced doofus, like when he did a double-fisted pump in the cab of a big rig or on his way to a 9/11 commemoration. But when it’s frozen in photographs, the fist hardens into a defiant, menacing embodiment of authoritarian swagger.

Trump’s presidency opened with the image of him raising his clenched fist at the end of his inaugural speech, in which he’d embraced the nativist slogan “America First” and called for “total allegiance” to the nation. It signaled not a transition but a power grab. This July 4, he posed, fist aloft, in front of Mount Rushmore before denouncing “far-left fascism that demands absolute allegiance,” a rhetorical denial of his own anti-democratic instincts that a historian noted “echoed a classic technique of past fascist leaders.”

Like so much of Trump’s flirtation with autocracy, the fist pump hides its darkest intentions behind plausible deniability: If athletes, musicians, and kids can lift or waggle their fists in excitement, why can’t the president, or his fans? And isn’t the raised fist also the symbol of Black Power and leftist solidarity? In late June, Trump retweeted a video of a fist-pumping supporter in Florida shouting “white power!” The White House claimed the president had not heard the slogan but remained impressed by the “tremendous enthusiasm” on display.

Even if the fist’s ideology is gloved, it is an obvious articulation of Trump’s constant need to assert his energy and dominance, not just to us but to himself. It’s a flash of power posing, of “gestural metonymy”: A fist is powerful, therefore forming a fist imbues you with power. The earliest photos I’ve seen of the Trump fist pump are from the 1990 opening of his Taj Mahal casino in Atlantic City. In them, he stands next to a giant magic lamp, like he’s just had his wishes fulfilled with the erection of another tower with his name on it. (If you think all this armchair psychologizing is, um, getting out of hand, let me just add that this is a man who was so psyched out by Spy magazine mocking his allegedly short fingers in the ’90s that he was compelled to announce the correlation between the size of his totally-not-tiny paws and his penis during a primary debate in 2016.)

Coming from a master of branding boondoggles, Trump’s fist is easy to dismiss as more ironic than iron, a slight of hand distracting attention from a flawed product. (After Trump went bankrupt, the Taj would eventually be sold off for 4 percent of its original value.) Yet as with so much of Trump’s behavior, the fist pump is no less terrifying for its brazen dumbness. No doubt it will provide one of the final images of his presidency—a valedictory, ham-fisted attempt to brandish his grip on our democracy even as he walks away from the carnage.

Dave Gilson

One morning when the pandemic was a few months old, a roommate walked past me as I was cooking breakfast. He then turned around, confused.

“Are you making fucking deviled eggs at 9 a.m.?” he asked.

“Yes,” I replied, and we laughed. But to be clear, I was not merely making deviled eggs. I was making Jacques Pépin’s “Eggs Jeannette“—a dish his mother made him when he was a child. It’s just one example of how this 85-year-old master French chef guided me through 2020 with his calming videos explaining how to cook for myself in ways that felt personally affirming, tender, even loving.

Pépin explains the secrets of Eggs Jeannette in a video, one of many the longtime cooking show host has uploaded through PBS’s YouTube page this year. He boils some eggs, disyolks them, combines the disyolks yolks with a persillade (parsley and garlic chopped together) and adds a bit of milk. He then adds this combination to the whites—making deviled eggs. But here’s where it gets interesting. Pepin then fries the deviled eggs in olive oil (yolks side down), gracefully using a fork to flip them. He places the fried deviled eggs atop a mustard vinaigrette, created with egg yolk detritus. Following the master, that morning, I too sprinkled some parsley on top.

As with most of Pépin’s recipes, this one is both simple and elegant, tasty when eaten and appealing when served. Granted, it takes more time than scrambling, but far less than you’d expect. I’ve loved making Eggs Jeanette, even on a weekday morning, moments before a Zoom call, which, of course meant I was late and would need to turn off the video so I could eat. And yet, that day—and on many other mornings during this year—I felt as if this was exactly what I needed to do.

“My mother would be proud of me,” Pepin says at the end of the video, looking affectionately at the dish. “Happy cooking.”

For the past few months, I have been happily, maybe a bit compulsively, cooking eggs (or should we say oeuffs?) with Pépin. I have watched his new PBS videos, “American Masters at Home,” and his classic “Fast Food My Way.” I have made his soufflé, his country omelet, his French omelet. I have learned the correct techniques with which to scramble, fry, and poach an egg. I have heard him say, time and again, beat the eggs firmly by going side to side in a bowl with a fork. I sprinkle herbs on top. He picks his herbs his from his garden; I pick mine at Safeway.