The Trust Women clinic in Oklahoma City. Sue Ogrocki/AP

Roe is dead. In the coming weeks, abortion will be banned in 13 states with trigger laws, and 13 more are likely to severely restrict or end abortion access. As my colleague Becca Andrews said earlier this week, it’s not an exaggeration to say “the sky is falling.”

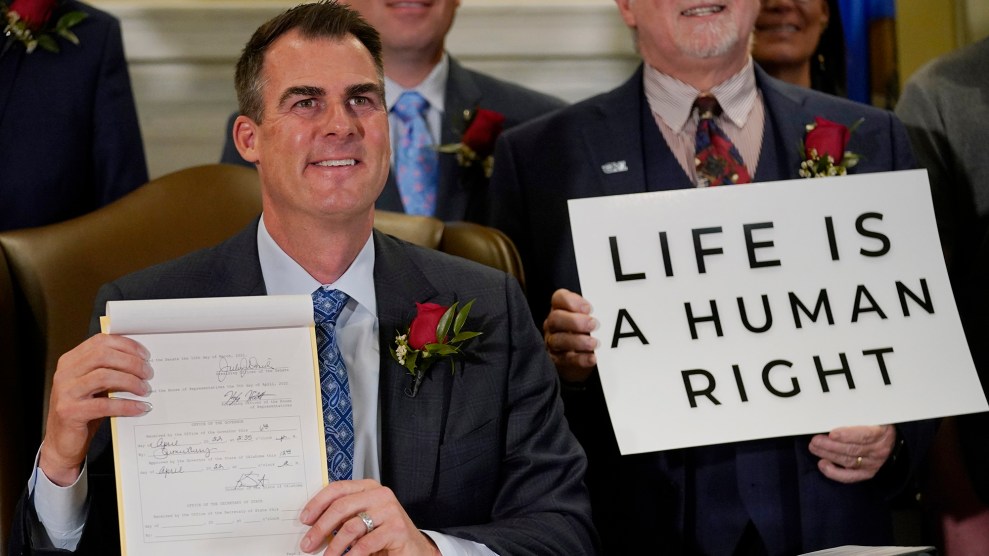

While a post-Roe world is now the reality nationwide, it’s already been reality in Oklahoma; in May, Republican Gov. Kevin Stitt signed a bill that bans abortion at fertilization and the bill went into effect immediately. Even before the bill, access in Oklahoma was dire, impacted drastically by patients fleeing Texas’ SB 8, which banned abortion at six weeks. When the Texas bill went into effect, the University of Texas at Austin found that 45 percent of patients unable to get abortions in the state traveled to Oklahoma. But now, those Texans and Oklahomans are traveling to other states, including Kansas. In fact, Kansas shares three borders with states likely or certain to ban abortion since Roe has been overturned. It didn’t take long Friday for the new Supreme Court ruling to further stresses the already-precarious system there:

Patients immediately started calling Kansas from all surrounding states saying their abortion appointments were canceled and hoping we can make room for them….

— Christina Bourne, MD, MPH (@xtina_bourne) June 24, 2022

Dr. Christina Bourne is the medical director at Trust Women, an abortion provider with clinics in Oklahoma City and Wichita, Kansas. In the last several months, they’ve dealt with the end of access in Oklahoma and seen how that ban impacts their ability to provide care in Kansas, where there is no trigger law or current legislative proposal to immediately end access. Earlier this month, before the Supreme Court ruling was made official, I spoke with Bourne about what she has learned from operating in a post-Roe reality, and what she wants providers everywhere to know about how to care for the patients who are now more anxious, more weary, and often more pregnant than before. Our conversation has been edited and condensed for clarity.

Let’s start with your Oklahoma clinic. What have the first weeks under the law that bans virtually all abortions looked like for you?

We, frankly, legally cannot provide any abortion services. And we’re trying to figure out the legal landscape in terms of us even doing some pre-care, like ultrasound dating or scheduling—like, can our Oklahoma staff make appointments for patients in Kansas? It’s been just a lot of confusion. In no way is anybody shocked or surprised. You know, we’ve been saying that this is going to happen for years now. And of course because of the way that things are going in our country, we’ve been anticipating this for some time. So we’re not shocked by any of it. But just trying to figure out strategies and next steps.

As someone who has worked hard to prepare for this situation, what has been surprising to you actually living through it as a provider?

I feel like that frog in the room temperature pot of water. And just slowly the water is increasing temperature around me. It feels like we just are accustomed to this being our new normal, and are really doing our best to talk with staff and hold space intentionally for staff because these are hard days. This is just what abortion care looks like now. Now, I’ve just become accustomed to this, but I imagine it will be a pretty rude awakening for a lot of people, especially for people who feel like this is “the beginning of things getting bad.” It’s like, “Oh, no, mostly baby boo, things have been very bad.” Just nobody has listened.

In Kansas, how have things changed both in the last year since Texas implemented SB 8, but then also in the weeks since abortion access ended in Oklahoma?

Kansas is just feeling more of the desperation of our region. Call volumes drastically increased, we’ve hired more staff and are in the midst of creating a call center. We’re seeing more and more medically complicated patients, which is really just an indicator of the health of our region. You know, people are coming in with communicable diseases and chronic illness in their 20s, and things like that. And then people are just at higher gestational ages, further along in pregnancy, because people are trying to call and schedule an appointment, and it just is a lot of work for patients to travel 10 hours from Houston or whatnot to Wichita, Kansas. We’re seeing a lot of Oklahomans and a lot of Texans.

When operating under these parameters, where are resources short and strained? How do your priorities change for the clinic?

I feel like it’s wild to even say, but our priority is staying open and seeing patients every day. I feel like when your day-to-day life is about struggling to exist, it’s really hard to actualize as an organization, or to innovate as an organization. Our day-to-day existence is about keeping our doors open and our day-to-day conversations involve that. It’s unfortunate because it truncates our ability to grow and blossom and refine and be slow and intentional in the work we do when it’s just like, you wake up every day to your fresh new hell.

We made an organizational shift in October to only provide abortion care really just based on the needs of our region. That’s not to say that Kansas and Oklahoma have a bunch of providers who are able to do free or reduced-cost gynecological care services. Or that a lot of people know how to do gender affirming care. But the unique thing that we can provide is abortion care. So we made the decision to pivot into that and really maximize and perfect how we do that.

How is this impacting staff in Oklahoma and Kansas?

I feel like people’s morale is low. People are sad. People are coming to work in Oklahoma, and there’s nothing to do. And so that feels bad. I feel like work defines us a lot. So people feel purposeless, which is just internalized capitalism, but people are bummed and people are mourning what was a really beautiful, vibrant space where people worked so harmoniously together. It really was beautiful to be a part of, and I’m really honored to have been a part of that.

I’ve seen this sentiment that in states where abortion access is more protected, we don’t have to worry about Roe being overturned. Based on your experience, what do you think patients in states where abortion is protected can expect to see when Roe is overturned?

What happens to one of us happens to all of us. Borders are made up, people can drive to your state, people will fly to your state, and people will mobilize and go get their abortion care where they can. Colorado, Illinois, Kansas, and Minnesota right now will be the hub for the Midwest and the South, and we need to be putting in a lot of effort to mobilize resources and anticipate later gestational age cases, and at least start having those discussions of what shifts your organizations will need for a massive influx of calls. I mean, we saw what happened with Texas, which is the second most populated state, and how that really crushed our Oklahoma infrastructure.

I just can’t reiterate enough how desperate people were for the care that they deserve, that they should be able to get in their own cities. It’s really bleak. People are weary, and they’ve traveled and haven’t slept, and are anxious and stressed and in a place that they don’t know and everything feels scary. And they don’t know if they need to lie about their abortion in their home state or say that it didn’t happen. Or, let’s say, god forbid, you start bleeding when you’re driving, where are you safe to go get care? People just overall are really scared of what all this means for their day-to-day life.

What are your conversations like with patients? Have they changed?

I remind people that we use the same medications for miscarriage as we do for abortion, and that we do the same procedure for miscarriages as we do for abortion. If people need to reframe this experience for their life, for their safety, for their medical history, they can just simply say that they had a miscarriage and that nobody other than them needs to know the difference. That’s not to say that you can’t be radically pro-abortion in this case, but it’s also just the reality of the situation for many people, they can’t safely say that they’re having an abortion. I say it to every patient, it’s part of my script. I have like, a five-second spiel. This is something that I’ve always known, but to really codify it in the same spiel that I give folks every day has developed, I’d say, over the last year.

What are the barriers to expanding access to meet the demand?

Internally, in our clinic, we’re thinking very specifically about workers’ rights, like what number of staff do you need to accommodate the calls while still recognizing that people deserve health benefits, maternity leave, sick leave, things like that. We frankly need an increased number of staff, which of course then comes down to funding. We’re a nonprofit. So a lot of our organizational income, of course, comes from clinics, but also from donations. So we just need more money to take care of the staff. And our building is quite old; it was George Tiller’s original clinic. It has been bombed, it’s been flooded. So we just have a lot of plumbing issues, we need better Wi-Fi to run through the building.

And then there’s physicians. We need more physician coverage and specifically more weekday physician coverage. Not that I’ve given up on physicians locally providing care, but the local climate in Wichita is definitely not a pro-abortion climate, even amongst physicians. So I would love to have local physicians, but a lot of our providers are fly-in providers, and most already have full-time jobs Monday through Friday. So they say, “We can come on the weekend.” But that’s the only time that our staff gets to see their children and also have a break.

And what number of physicians know how to do dilation and evacuations [D&Es]? Not a lot. We generally use that for abortions that are over 15 weeks. And who has been trained in D&Es, who has gotten access to that training, is rooted in oppression, racism, sexism, and classism, so we’ve found it’s mostly old white, OB-GYNs who know how to do this, and it’s difficult to train people. It’s a very common medical procedure, yet a procedure that not a lot of doctors know how to do, nor is included in medical school curriculum or residency training for most specialties.

Wow, I don’t think a lot of people are aware of how few providers there are with these skills. And now you’re having to perform more of those complicated procedures because the influx of patients?

Absolutely. If somebody finds out they’re pregnant within the first trimester, like at 12 weeks but then has to wait three, four weeks to get their clinic spot, absolutely that puts them into that 15 weeks spot where now it’s like a completely different procedure. If we were able to take care of them when they had originally called, it would just be a more simple procedure, which is more accessible for most people’s skill level.

Everything has such a domino effect.

I know, everything’s trash.

What would you say to providers in the 13 states where very soon abortion access will end?

Oh, God, how crushing. I mean, it’s complex, because we’ve anticipated that this is happening. And then when it does happen, there’s a mourning process. It hurts your ego in a way too, because you spend decades of your life training to do this work, and to have it invalidated for reasons that are not rooted in evidence or science feels frustrating. It’s a lot to take in. I would just say that any emotional response is valid and normal, whether it be that you laugh or dissociate, or feel more ignited to do things, or are just listless.

I want all providers to know that we do not need to criminalize any pregnancy outcome. People should be safe to come to us. Regardless of what your moral compass says about their behavior, it truly doesn’t matter, you just simply take care of folks.

What does the future of the Oklahoma clinic look like? Why is it so hard to pivot back into providing other services when you can no longer provide abortions?

Our clinic is still open. And I think we have a lot of hopes and dreams for the clinic space as we all acknowledge and accept that probably we’re not going to be able to do abortion there. We’ve been talking about making it more of a mutual aid space. We’ve reached out to harm reduction organizations, other community organizations, those who do outreach services. But I do think that unfortunately capitalism just doesn’t allow a mutual aid organization just to be chilling and running—it requires financial payment and rent and we have to pay our staff.

And a lot of our staff, they want to be here and they want to be doing abortions. So, I think we would probably lose some staff; we also have to hire more local staff. I’m the only staff physician of our organization. And I’m only one single human, so me pivoting to gyn care, STI, gender-affirming care all requires more of my own focus.

And then for gyn services, it’s like, “Oh, why not just do pap smears?” But then what if you have an abnormal pap smear? Who do you refer patients to for a colposcopy? Who’s going to work with us to do a colposcopy who is a trustworthy physician and individual? So it requires a lot of other systems that were unfortunately kind of never put into place, and were a big influence on our decision to just focus on doing abortions, because a lot of those other systems needs were left behind. And I think a lot of the care that was being provided outside of abortions was pretty subpar.

Like you said before, Trust Women is just trying to survive, just trying to stay open. But what are your longer term goals for Trust Women? What do you hope the clinics look like in a year or in five years?

Our clinic in Wichita, I really want it to be a five day a week clinic, and perhaps even have multiple shifts within each clinic day. To really have it be a center of excellence within abortion care—both in terms of receiving an abortion and being trained to do abortion. I want it to be a space which is safe for all patients and safe for all learners, regardless of demographic or social situation. And have our staff and our providers be representative of diverse backgrounds in the broadest sense.

What, if anything, is making you hopeful?

What makes me hopeful honestly is within my community and organization, people are really invested in this and the success of Kansas at the very least, and our space staying open. So I feel like my like co-workers, my co-conspirators, give me like a lot of hope for the ingenuity, flexibility, and creativity of people who work in abortion care.

Correction, May 30, 2023: This article has been updated to reflect the narrow exception in Oklahoma’s abortion ban for abortions performed to save the life of the mother.