Mother Jones; Ron Sachs/Zuma; Jon Elswick/AP

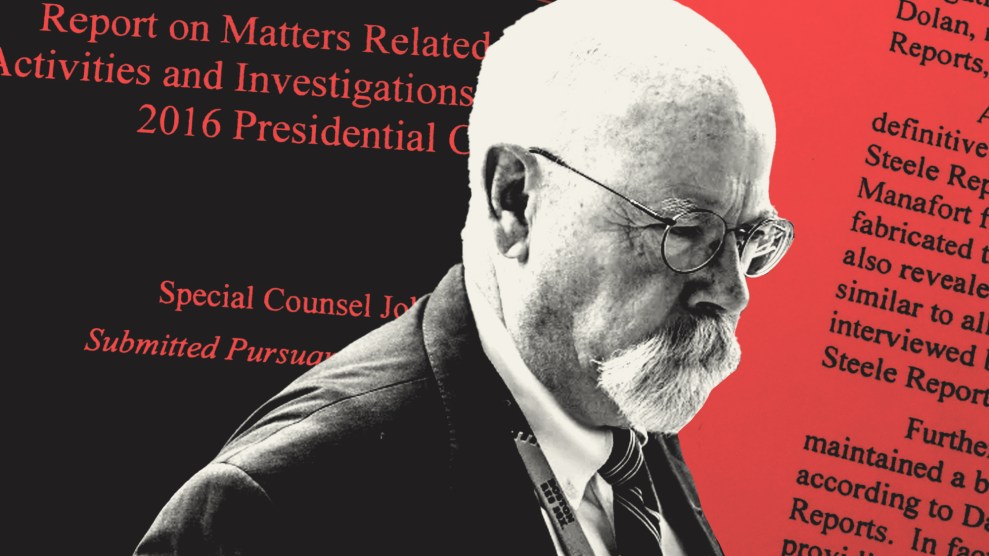

John Durham’s final report blasts the FBI for using the so-called Steele dossier, a compilation of unconfirmed claims about Donald Trump and Russia, without sufficiently considering the chance that Steele’s findings contained deliberate Russian falsehoods. But Durham himself relies substantially on a sketchy intelligence product that may be Russian disinformation to push a partisan political narrative. And he does not even note the irony.

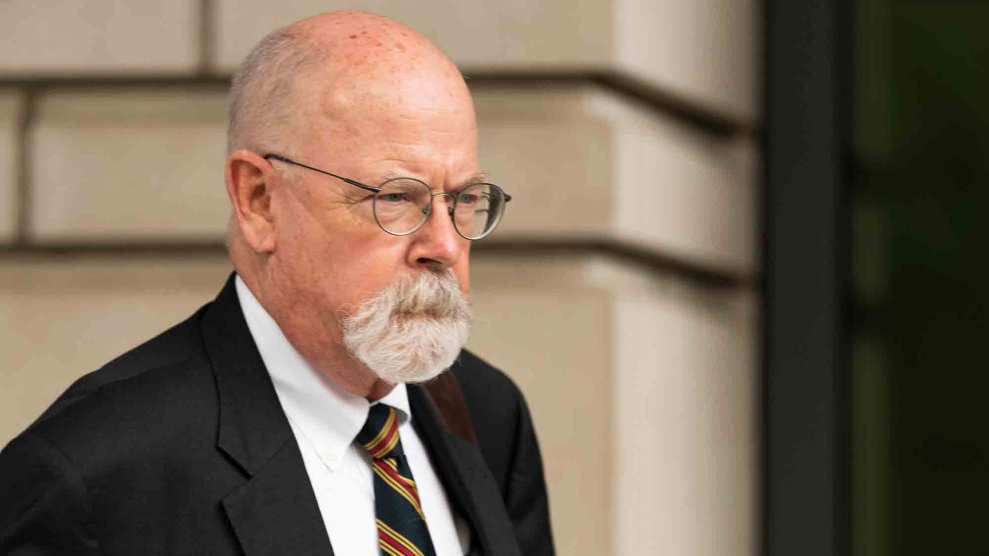

Durham, the special counsel who former Attorney General Bill Barr selected in 2019 to look into the origins of the FBI’s Trump-Russia investigation, may have succeeded in his apparent goal of serving up reheated scraps for a familiar retinue of hardcore Donald Trump defenders to feast on. House Judiciary Chairman Jim Jordan (R-Ohio) announced last week he wants Durham to appear before the committee on Thursday. But that testimony remains unscheduled. The Judiciary Committee did not respond to questions about the delay, which occurred with Durham facing substantial criticism.

Obituaries for his four-year, $7 million investigation have noted Durham’s repeated failures to secure courtroom convictions and pointed out how meek his conclusions were compared to the wild expectations of Trump fans. But a different shortcoming in Durham’s work—its astounding hypocrisy—may not be getting the attention it deserves.

The special counsel’s 306-page report refers 65 times to the “Clinton Plan intelligence.” That is a claim that Hillary Clinton, on July 26, 2016, approved a plan to “vilify Donald Trump by stirring up a scandal claiming interference by the Russian security services.” Where does this supposed intelligence come from? Those very same Russian security services. The report notes that the “Clinton Plan intelligence” came from a “Russian intelligence analysis” that US intelligence agencies got their hands on.

Think about that. To figure out how an American presidential campaign supposedly went about attacking a rival campaign, Durham relied on information US intelligence gathered on claims made by Russian intelligence agents about what they supposedly found by spying on Americans. That’s a pretty roundabout way to learn the kind of information you’d expect to see in “Playbook.” And this game of spy telephone was actually even longer than Durham details. According to the New York Times, US spies obtained their “insight” into Russian intelligence thinking from Dutch intelligence, which was spying on the Russians as the Russians spied on Americans. Durham seems to have found no other confirmation for his “Clinton Plan intelligence.” That’s reason enough for skepticism.

But there is a bigger problem. Russian security services did hack Clinton’s campaign to help Trump, according to the entire US intelligence community and the Senate Intelligence Committee. Yet Durham relies on those Russian spies for insight into how Clinton reacted to the hack. That is like the cops citing a bank robber who says the bank framed him.

Durham admits that the “Clinton Plan intelligence” may be a “fabrication.” Then he cites it anyway, extensively. He laments the FBI’s “startling and inexplicable failure” to use the supposed plan to put the breaks on the bureau’s Trump-Russia probe. He also suggests Clinton’s machinations may have “in part triggered” the FBI’s investigation.

Durham doesn’t explain that claim, but that didn’t concern Trump defenders. “The Russian collusion conspiracy was invented by Clinton operatives,” frequent Trump apologist Jonathan Turley wrote in the New York Post. “The Russian hoax was a figment of Hillary Clinton’s imagination,” Sen. Marsha Blackburn (R-Tenn.) declared.

This isn’t just false. It would require time travel. Durham himself confirms that the FBI launched its investigation into Trump and Russia based on events that occurred months prior to Clinton’s alleged July 26 approval of the plan. In April 2016, George Papadopoulos, a foreign policy adviser to the Trump campaign, met with a professor with Kremlin ties, who informed him that Russia “had obtained ‘dirt’ on…Clinton in the form of thousands of emails,” as Robert Mueller’s final report noted. A week later, according to Mueller, Papadopoulos “suggested to a representative of a foreign government that the Trump Campaign had received indications from the Russian government that it could assist the Campaign through the anonymous release” of damaging material. When hacked Democratic emails were indeed published—by WikiLeaks on July 22—this foreign diplomat alerted US officials about what Papadopoulos had said. The FBI quickly launched an official investigation into the Trump campaign’s Russia ties in response to that tip, Durham notes, while arguing they should have begun only a “preliminary investigation.”

It was the same Russian hack, not Hillary Clinton, that drove media attention, even before the documents were leaked to the public. A June 14, 2016, Washington Post report—”Russian Government Hackers Penetrated DNC, Stole Opposition Research on Trump”—kicked off a boatload of stories about Trump’s financial ties to Russia and his fawning posture toward Vladimir Putin.

And for all we’ve heard about Mueller’s failure to uncover “collusion” or a criminal conspiracy between Trump and Russia, Durham in fact failed to dent the conclusion, reached by multiple investigations, that Trump’s campaign knew of and “expected it would benefit electorally from information stolen and released through Russian efforts,” as Mueller wrote. The Trump campaign’s litany of sketchy Russian contacts included campaign chief Paul Manafort’s secret 2016 contacts with a man the Senate Intelligence Committee labeled “a Russian intelligence officer,” who was seeking Trump’s backing for a Kremlin-approved plan that would have given Russia effective control of eastern Ukraine. Manafort meanwhile provided his Russian contact with campaign polling data. All by itself, the machinations of Manafort, whom the committee called “a grave counterintelligence threat,” refute Trump’s “hoax” claims.

Russia’s hacking, and Trump’s effort to exploit it, along with his extensive lies about the topic, drove media and law enforcement attention to it. Clinton’s campaign, as Durham labored to show, did try to exploit the scandal. But Clinton didn’t invent it. Or if she did, as we’ve noted before, she had the extraordinary luck of making up an accusation that turned out to be correct.

Durham evades this problem by focusing on Clinton supporters’ efforts to highlight allegations about Trump and Russia that did not pan out—in particular the campaign’s funding of the Steele dossier, the series of memos of unverified human intelligence that British ex-spook Christoper Steele compiled as opposition research on Trump. Steele’s stuff didn’t cause the FBI investigation. The agents only saw Steele’s memos in mid-September, long after launching the probe, as Durham notes. Nor did the material factor in the conclusions of the probes conducted by Mueller or Senate Intelligence Committee.

But the FBI did use the Steele’s memos in FISA applications allowing them to spy on Trump campaign adviser Carter Page. And Durham rips the bureau for relying on “unvetted and unverified” rumors. Durham also argues that the FBI failed to fully consider the possibility that Steele’s primary sub-source, Igor Danchenko—a Russian-born US resident who was once the subject of a US counterintelligence probe—misled Steele to help the Kremlin.

“In not resolving Danchenko’s status vis-a-vis the Russian intelligence services, it appears the FBI never gave appropriate consideration to the possibility that the intelligence Danchenko was providing to Steele…was, in whole or in part, Russian disinformation,” Durham says.

But Durham levels this criticism while leaning heavily on information that indisputably came from Russian intelligence, which has an obvious motive to mislead Americans. The “Clinton Plan intelligence,” like the Steele dossier, also came from a series of memos, the New York Times reported in January. But these memos were not just potentially influenced by Russian spies. They were written by Russian intelligence analysts, who claimed to base them on “conversations involving American victims of Russian hacking.” According to the Times, the memos made “demonstrably inconsistent, inaccurate or exaggerated claims, and some U.S. analysts believed Russia may have deliberately seeded them with disinformation.”

Durham admits, the first time he cites the “Clinton Plan intelligence,” that it may be total bullshit. The report quotes former Director of National Intelligence John Ratcliffe. who, when he declassified some of the same information in October 2020, said the Russian claims were unconfirmed and might “reflect exaggeration or fabrication.” Durham also quotes three Clinton aides separately calling the allegation “ridiculous” and notes that Clinton said that the claim struck her as “Russian disinformation.” But Durham does not otherwise address the possibility that the Russian analysis was a deliberate lie.

Instead he leans heavily on the supposed intelligence. And like the FBI officials who used Steele’s memos to justify surveilling Page, Durham cited the Russian memos in court to advance his cause. The same Russian memos that included the “Clinton Plan” allegation also claimed that the Russians had snooped on communications between an official at the Open Society Foundations—the pro-democracy organization founded by George Soros—and Rep. Debbie Wasserman Schultz of Florida, then head of the Democratic National Committee. The Russians claimed the duo had discussed a promise by then-Attorney General Loretta Lynch to limit the Justice Department’s probe into Clinton’s handling of State Department emails. But, as the Washington Post first reported in 2017, no other evidence supported this claim, and US officials suspected it was deliberate disinformation.

Still Durham cited the memos as evidence in a bid to obtain a secret federal court order to seize the Open Society official’s emails, according to the Times. After a judge found his evidence was too weak for a warrant, Durham used grand-jury power to demand documents and testimony directly from Open Society and forced the group to cooperate. He seems to have found nothing.

Durham used possible Russian disinformation while attacking the FBI for using possible Russian disinformation. That may seem confusing, but it helps clarify what the special counsel has been up to for the last four years.Working to arm Donald Trump and his allies with talking points to fault what they call the “weaponization of government,” Durham made himself their weapon.